Heavy Metal: The Making of the Movie (from August 1981)

Heavy Metal: The Making of the Movie (from August 1981)

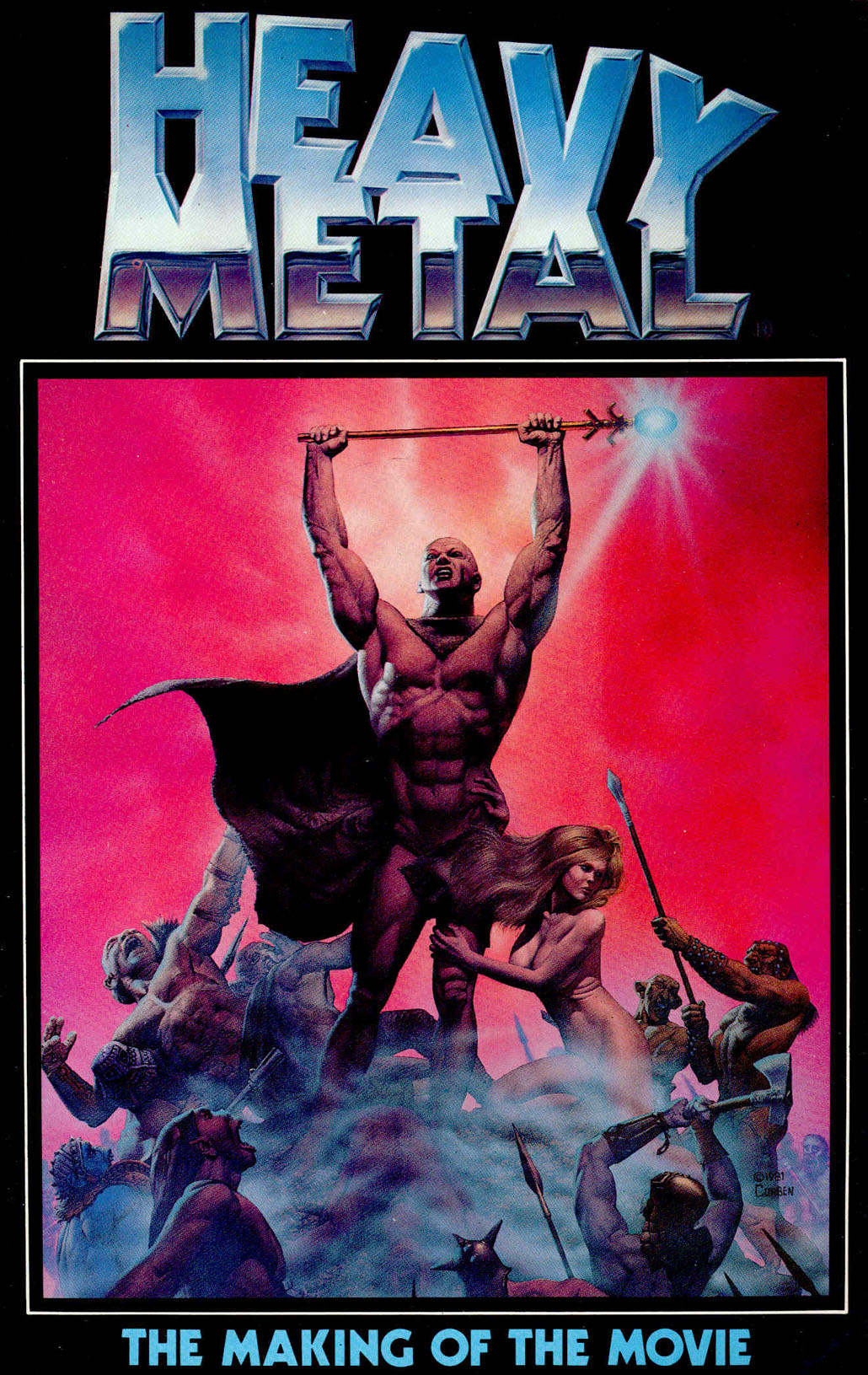

Heavy Metal, the movie, had its premiere 40 years ago today—July 29, 1981—and opened nationwide a week later. To celebrate the anniversary we’ve got a treat for fans: The “Making of” article that ran in the August 1981 issue of Heavy Metal. This will bring back memories and will likely induce a strong urge to watch the film. Enjoy.

NOTE: Additional images have been added to this article

by Brad Balfour

Take 70 animators from 14 different countries, guys who have worked on everything from Sylvester the Cat to J.R.R. Tolkien’s hobbits. Put them in ten different studios stretching from the West Coast to London, with the nerve center in Montreal, somewhere in between. Give them characters and situations devised by writers who have previously written the highest-grossing Canadian film ever, and a director who has worked with such notables as Buster Keaton and Harold Pinter. Add to this already inspired mix astounding graphics and design sketches by some of the world’s hottest fantasy-art geniuses, artists loved and respected worldwide. Don’t forget a producer who at 27 started raking in bundles in Canada because he produced a young horror-filmmaker’s surprisingly good and profitable ideas, and later coproduced the 11th-highest-grossing film ever. Finally, base this on a magazine of illustrated science-fiction and fantasy stories, material of international renown, whose contents are reviewed in major French newspapers on a par with the way high art is covered, and whose illustrators include artists from Japan to the Netherlands. Take it all to Columbia Pictures, who distributed one of the finest science-fiction films in years, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, where the executives on the Burbank lot say, “This whole package is so fantastic, let’s make it our big film for the summer’s end.”

I’m talkin’ about Heavy Metal—the movie; talkin’ about Heavy Metal—the magazine.

And it was like something from a dream—the spirit of fate or the force of coincidence at work—that while publisher Len Mogel was in Paris negotiating rights with a small French publisher to produce a French version of National Lampoon, his wife, Ann, picked up a copy of their new magazine, Metal Hurlant. Both the Mogels were enthralled with its contents—illustrated science fiction and fantasy for adults laced with a strong dose of the absurd, drawn like fine art.

Mogel was determined to publish an English-language magazine presenting this new artistic concept, and he quickly won over his colleagues. Heavy Metal began publication in April 1977.

Mogel and crew found that after a mere five issues premiered, Heavy Metal quickly garnered over 100,000 readers. It was then that they knew they had something remarkable in hand. A year later—with the phenomenal success of Matty Simmons and Ivan Reitman’s National Lampoon’s Animal House as inspiration—the dream of a Heavy Metal movie took form.

The connection between comics and cinema is a natural one. Both deal in illusion, in actualized fantasy. Continuity of image and simple storytelling separate the successful story, told either in panel-art form or on celluloid, from the mediocre. The telling of a story through connected image and dialogue has been attempted since the first caveman painted sequential images on stone. Film is merely the execution of that idea in a modern way. As for the conjunction of comics and animation—well, what else could there be? Drawn images on a screen—drawn images on a page.

The Heavy Metal movie cried out to be animated. What else could capture the absurdist/dadaist/surrealistic urgings of the mag’s original art? Not live action, for then the extraordinary is rendered as the everyday. To keep the material in the realm of the imagined—in the region of mind that can plan out an entire world in sequential drawings—was the only appropriate choice.

Just imagine: a person draws, from nothing but disparate images in the head, a cohesive whole composed of hundreds of little scenes (the longest sequence in Heavy Metal consists of 330 scenes) made up of close to 130,000 individual drawings. Finally it’s the experience of an audience exchanging belief in the regular world of the photographic for the totally unreal world of the drawn, which then takes on a life of its own. And Heavy Metal, the movie, goes even beyond that.

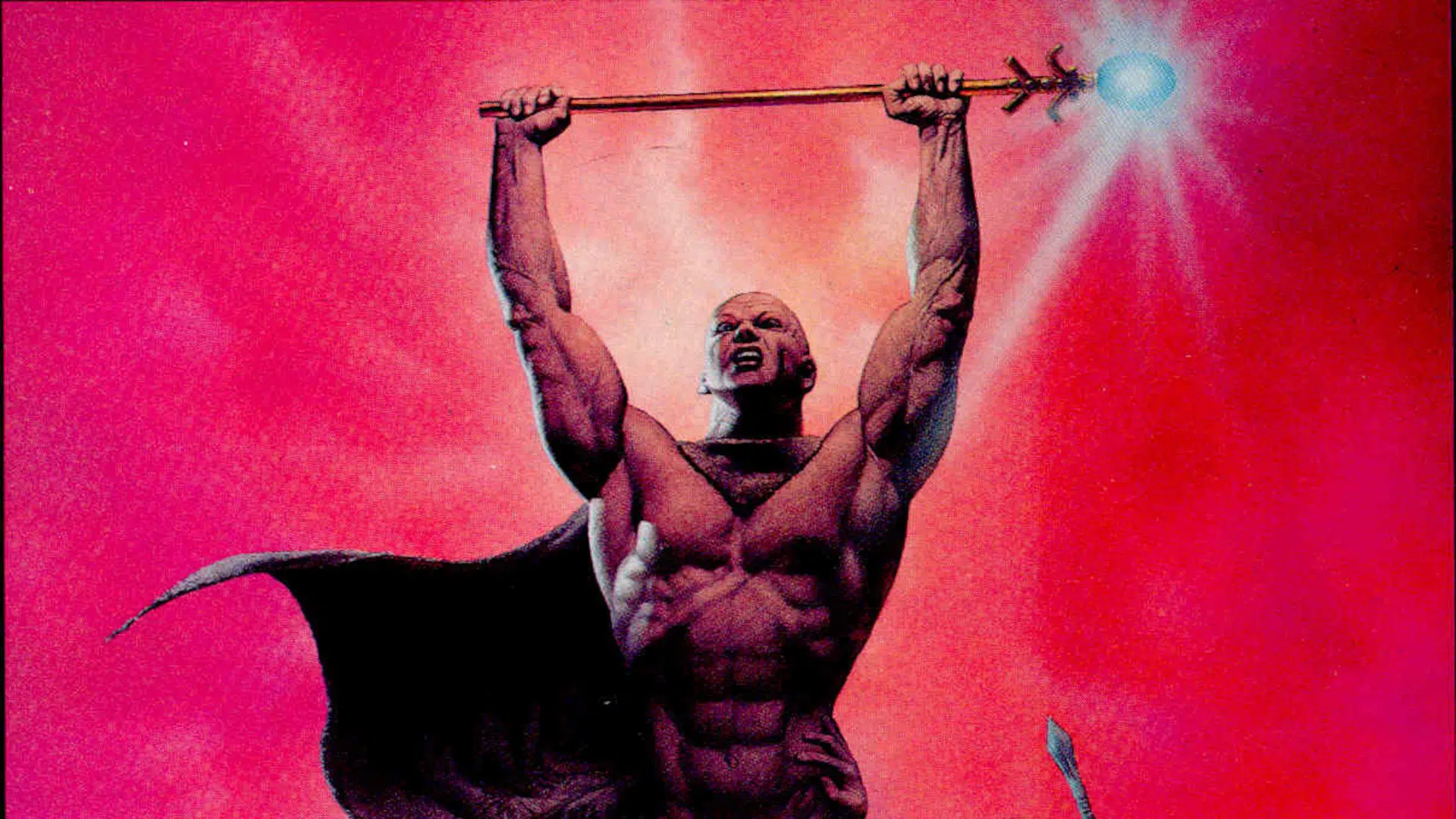

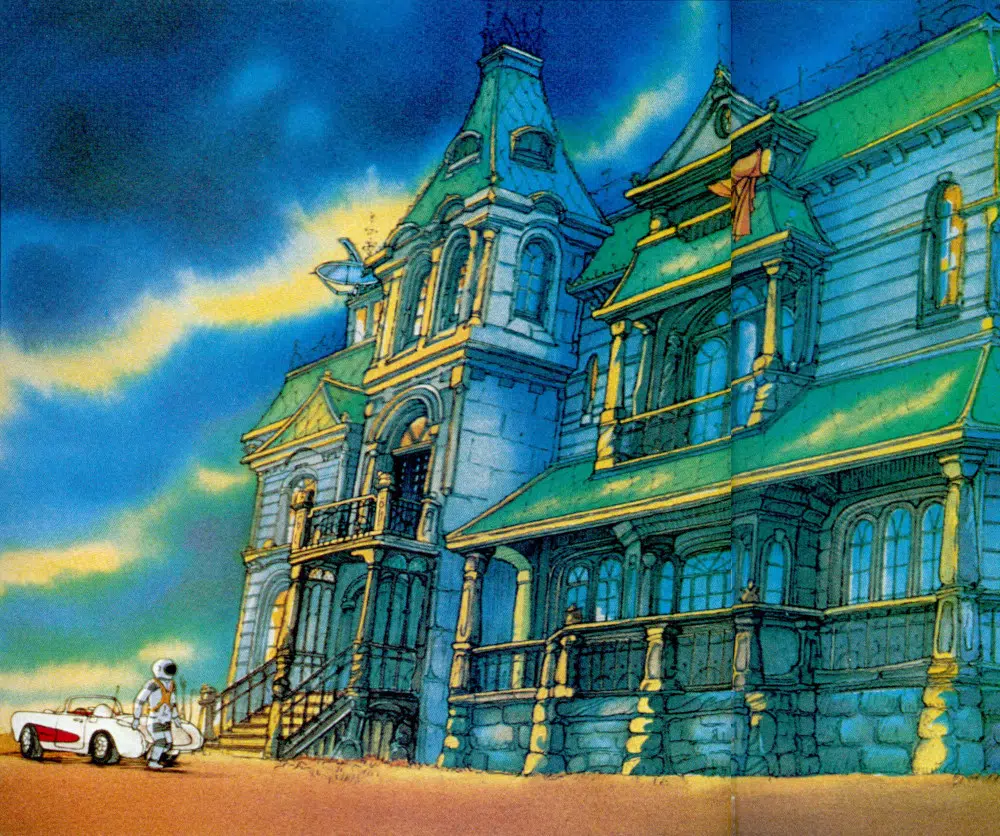

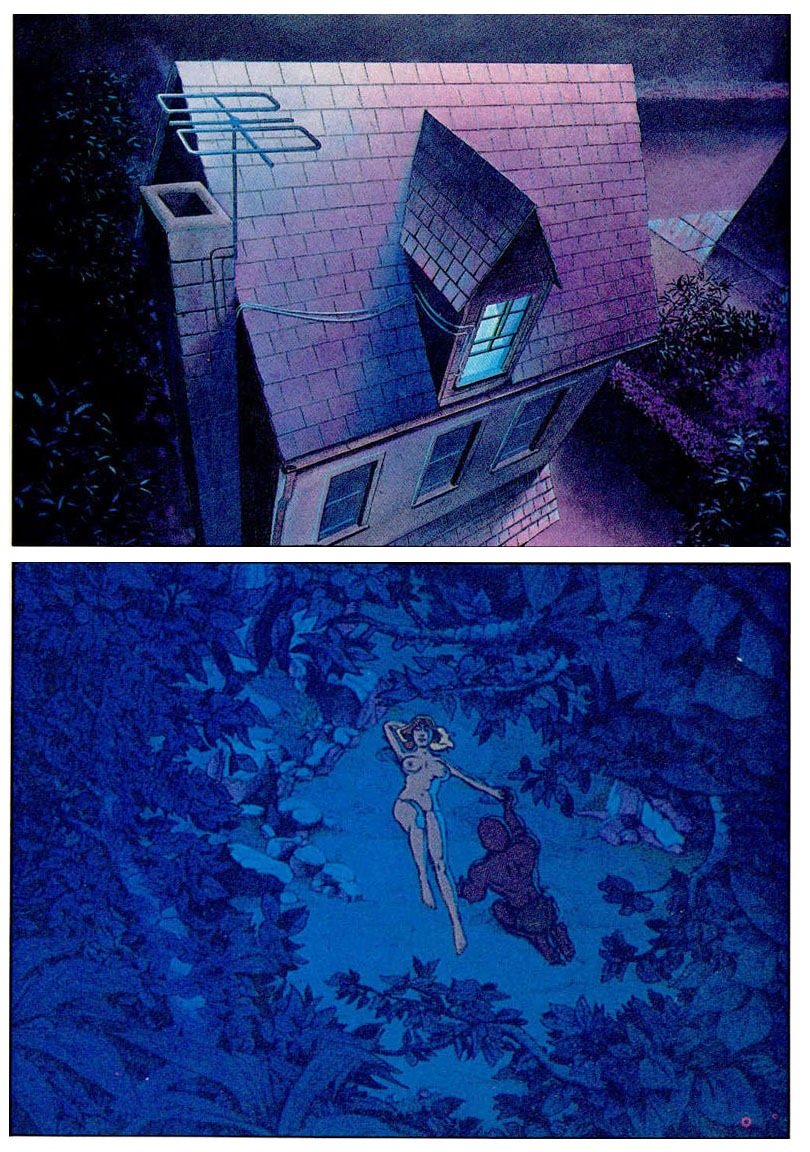

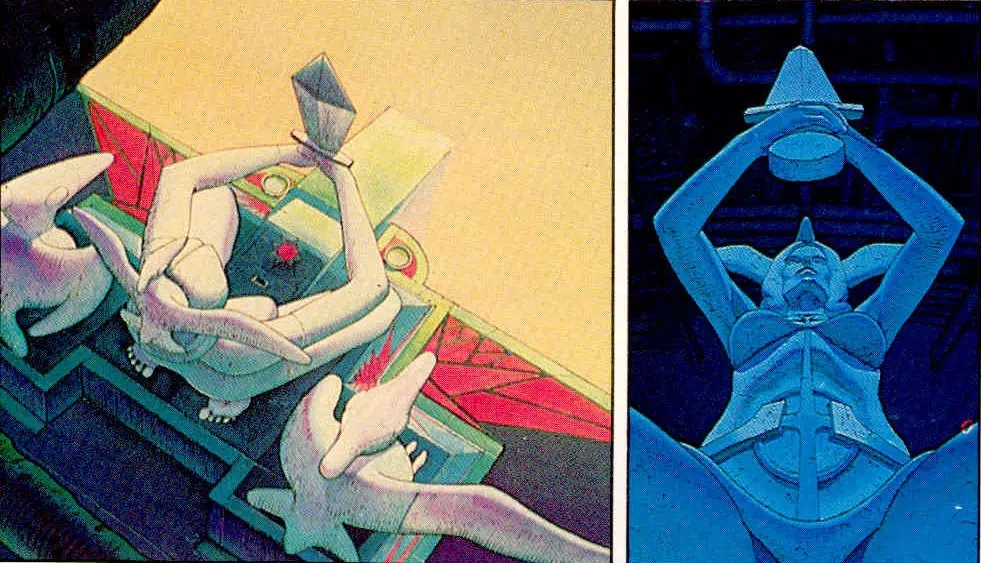

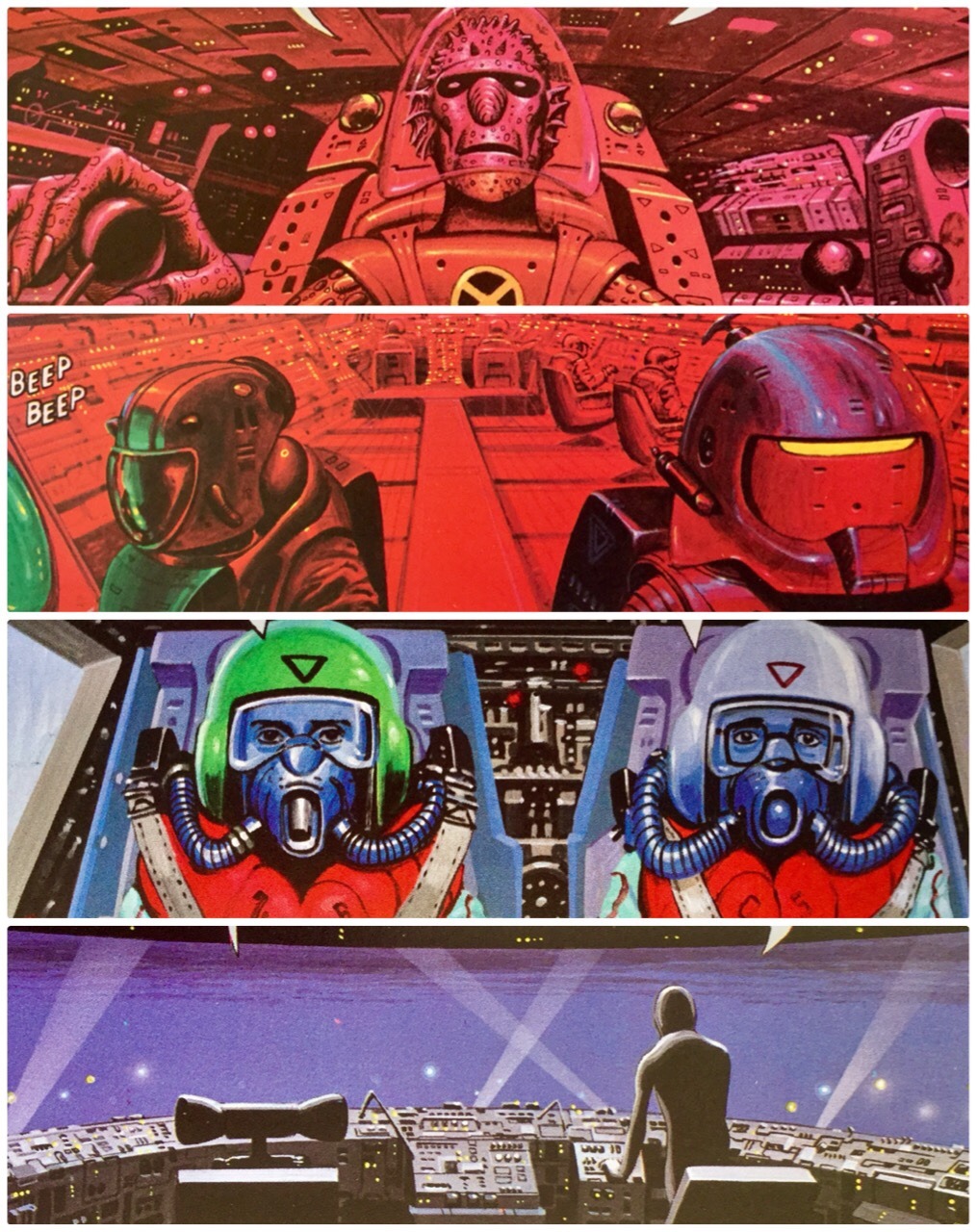

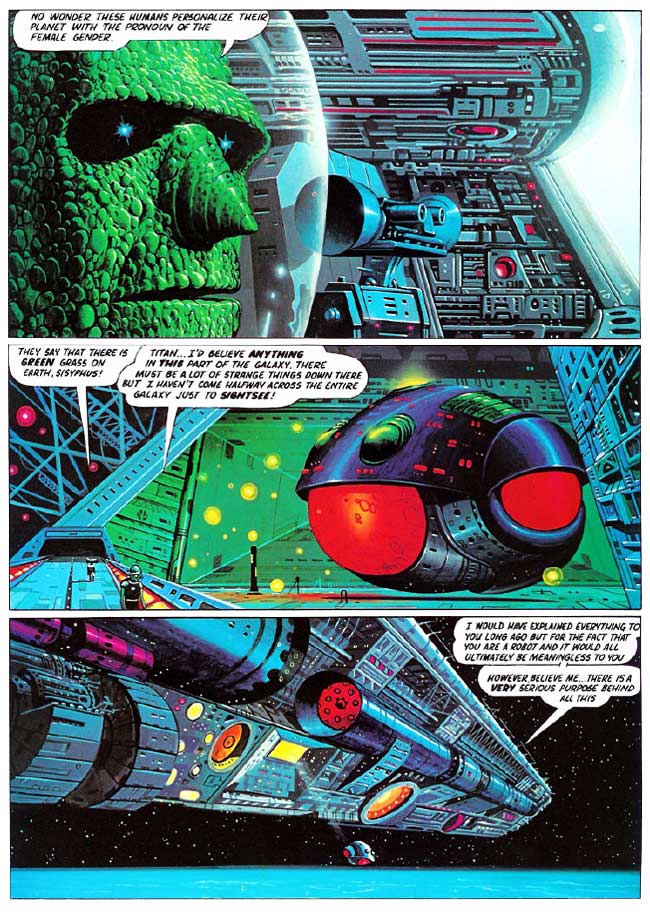

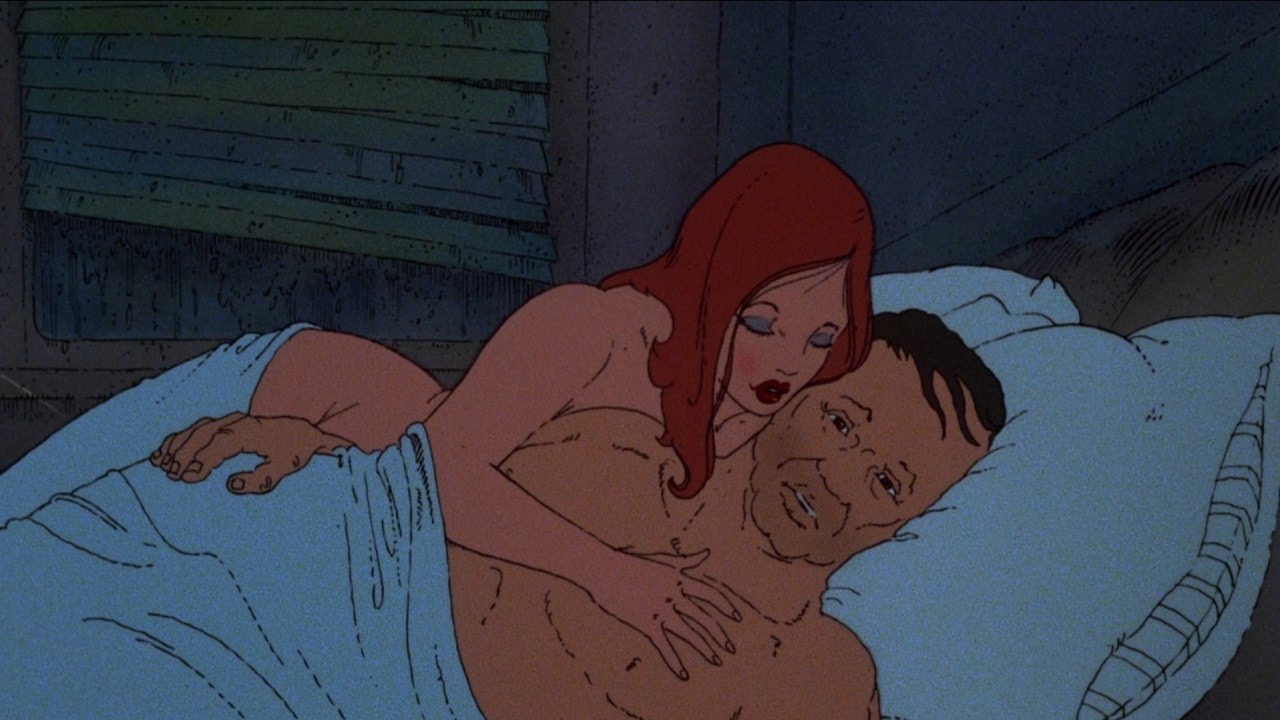

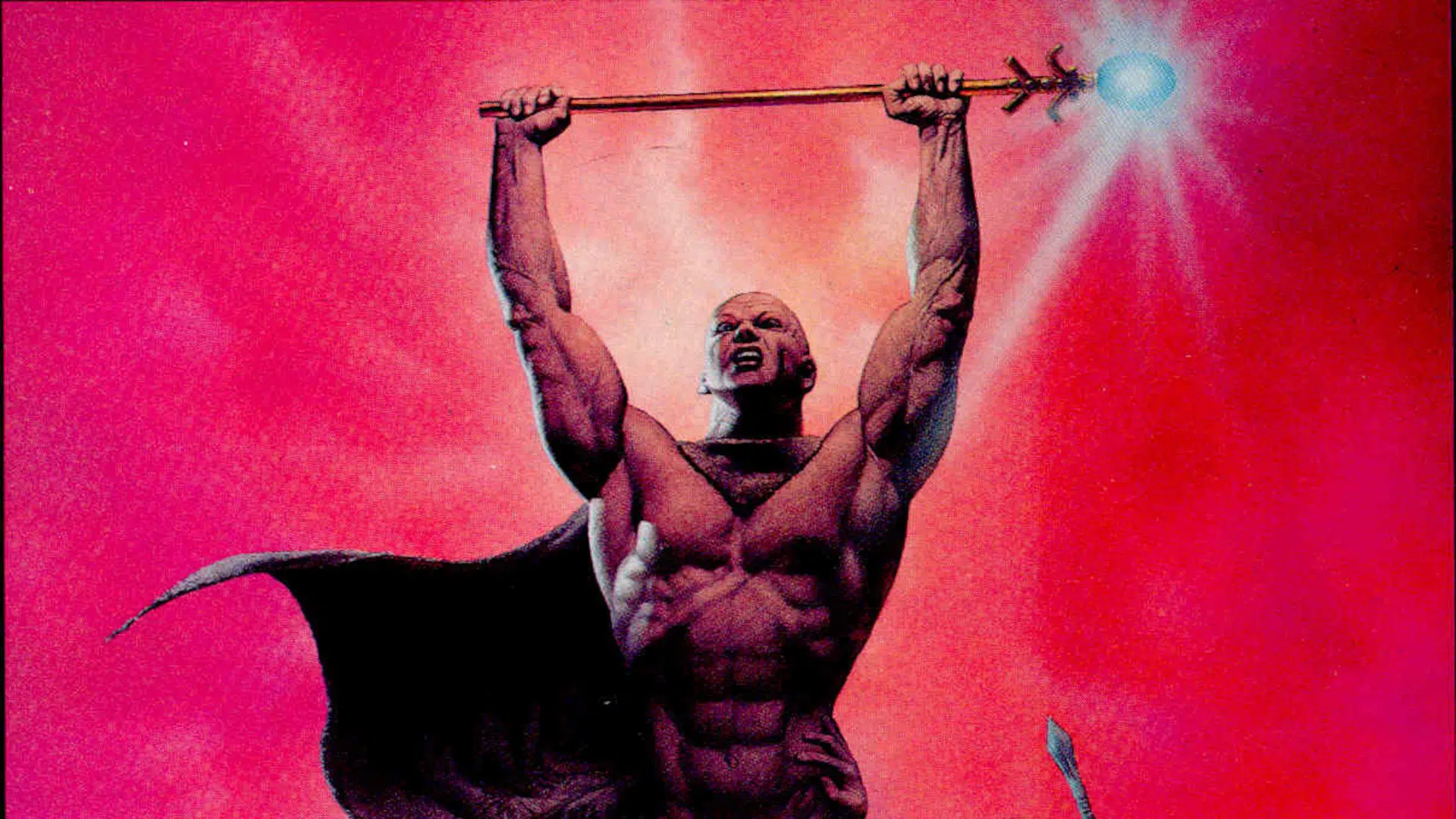

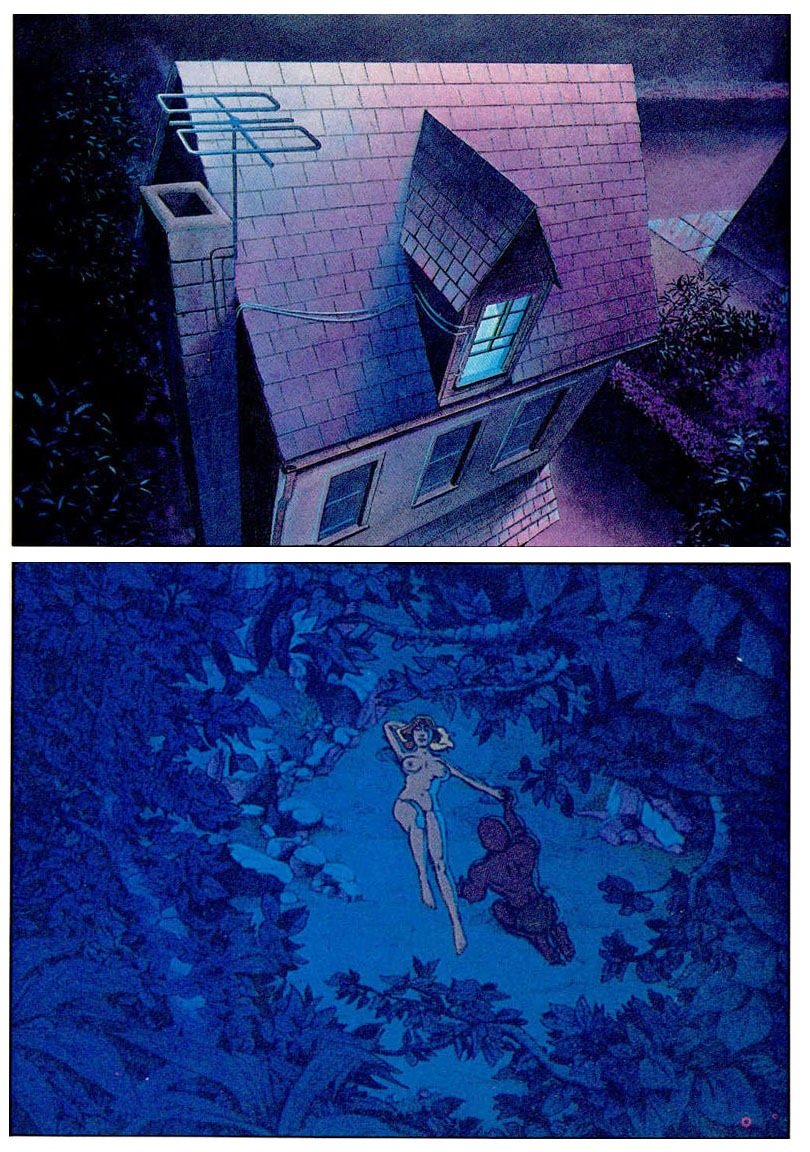

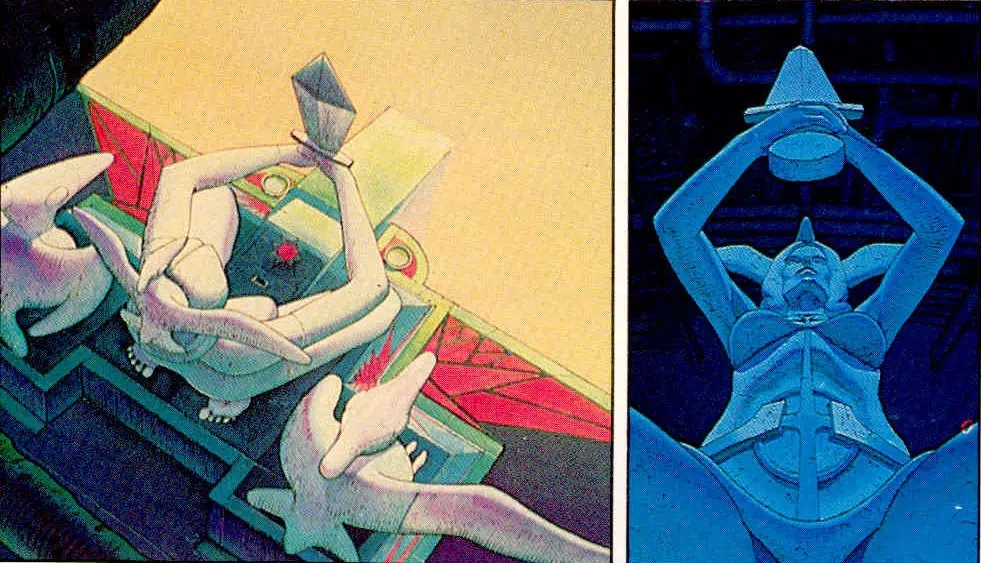

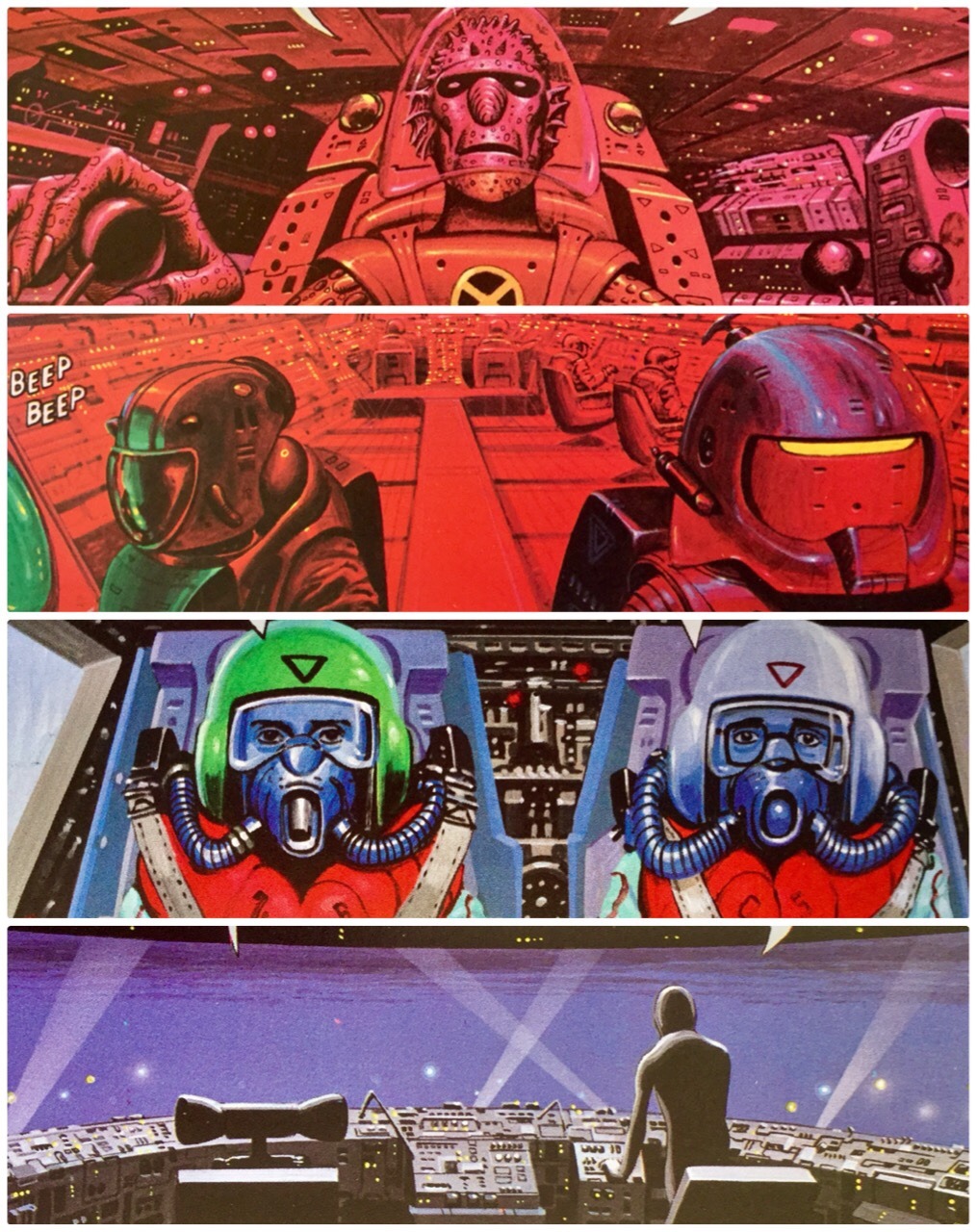

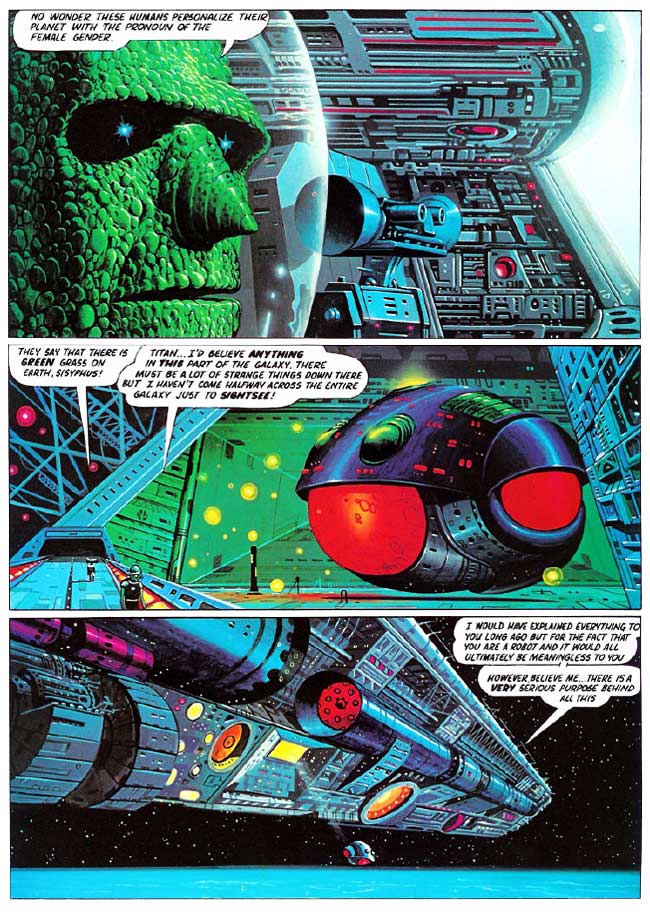

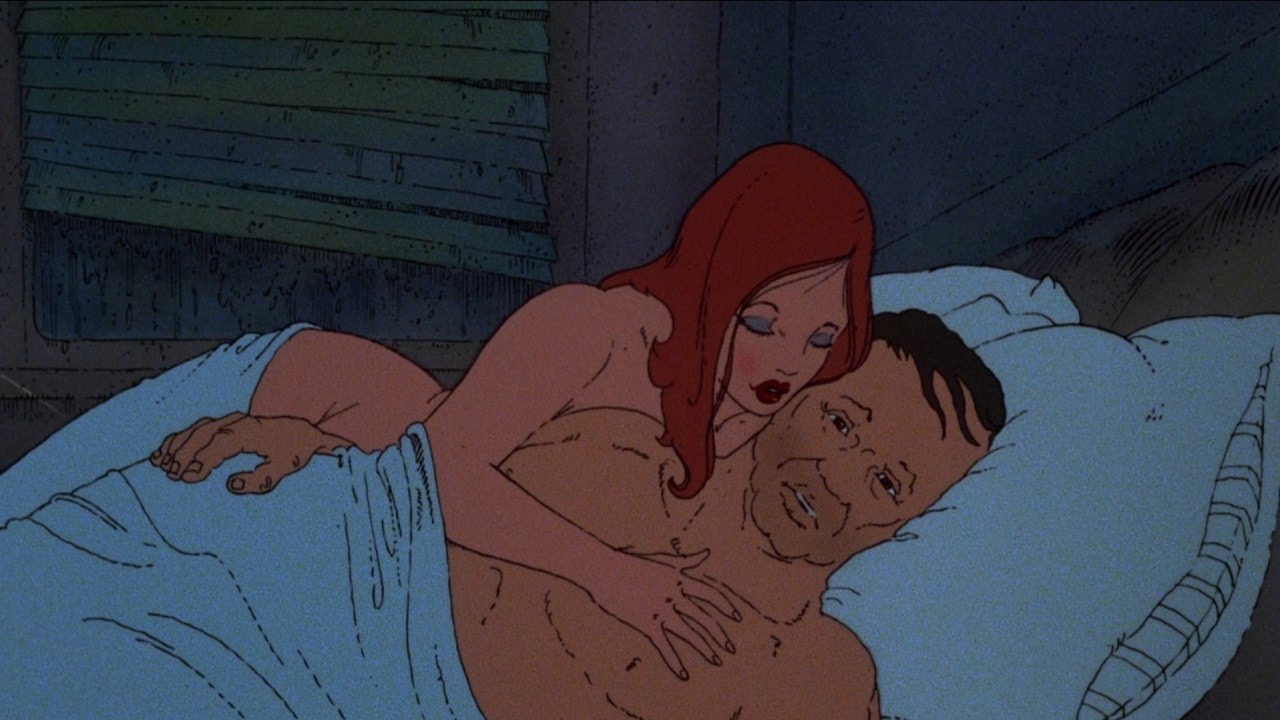

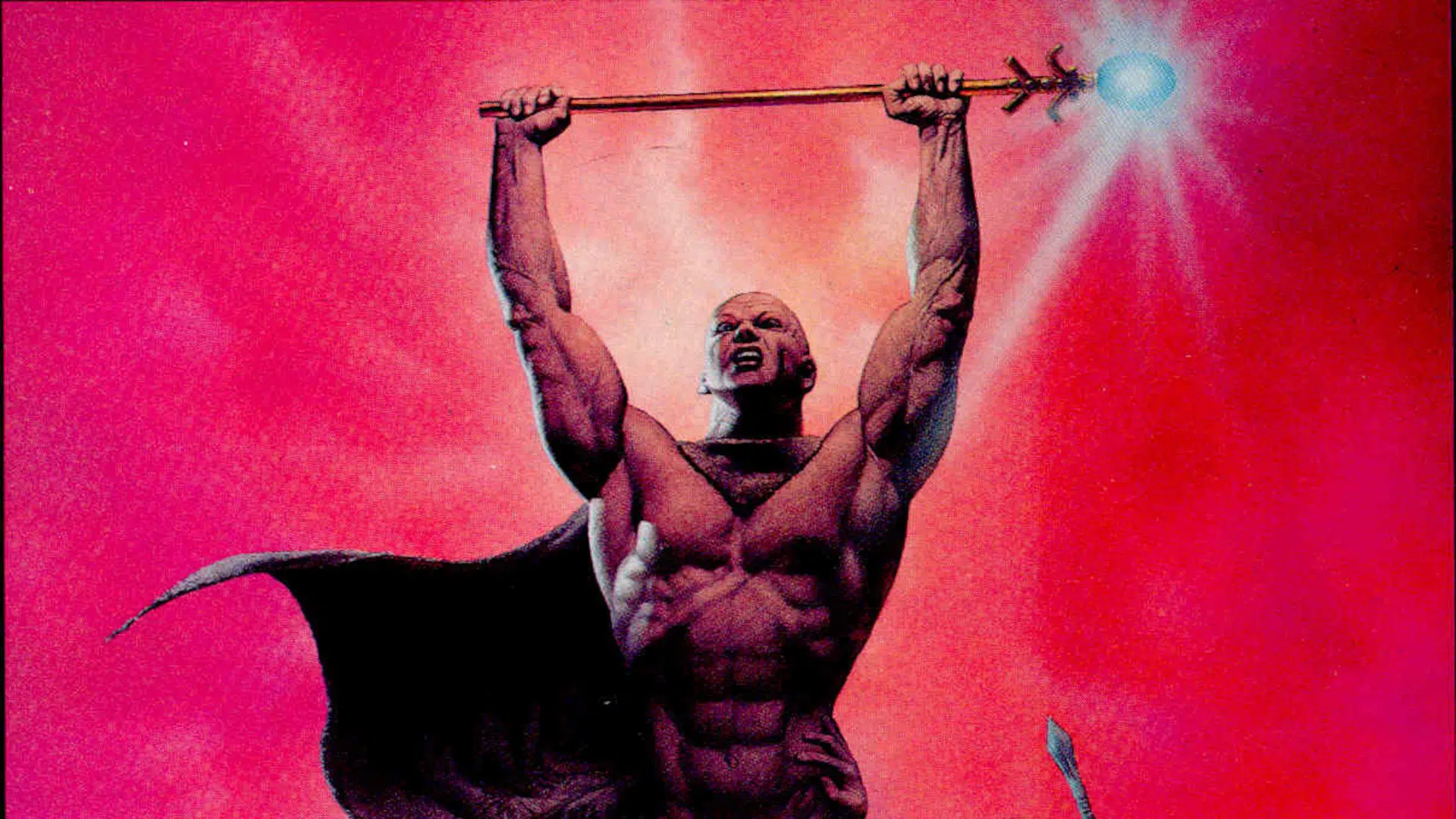

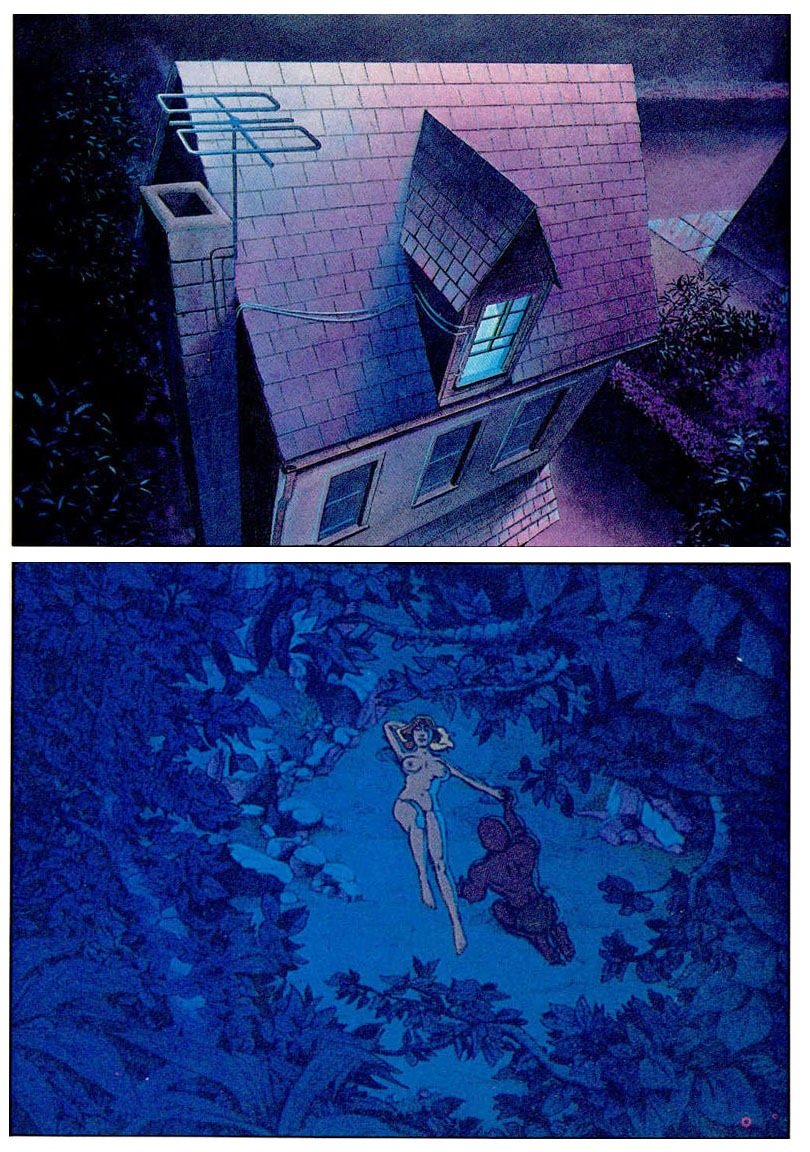

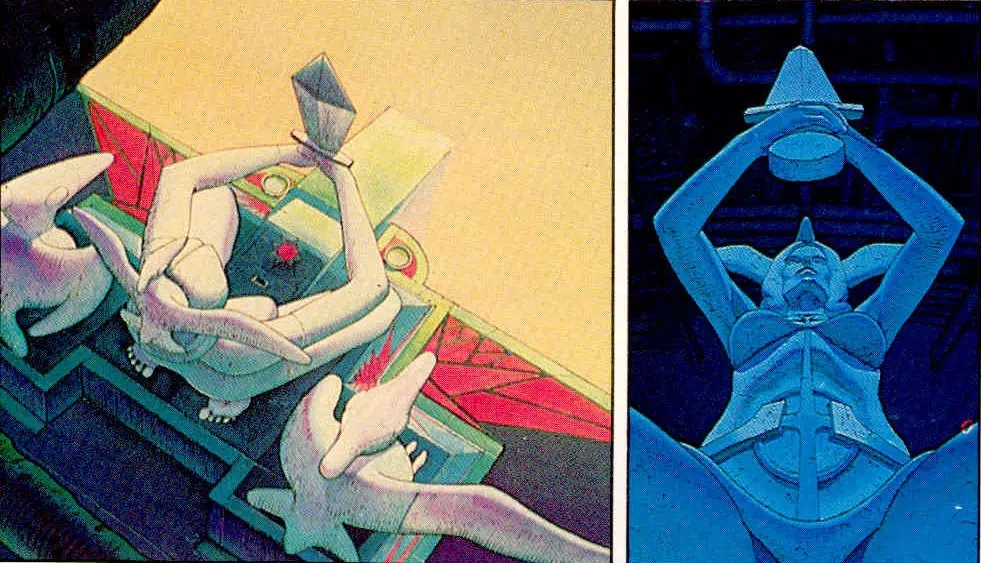

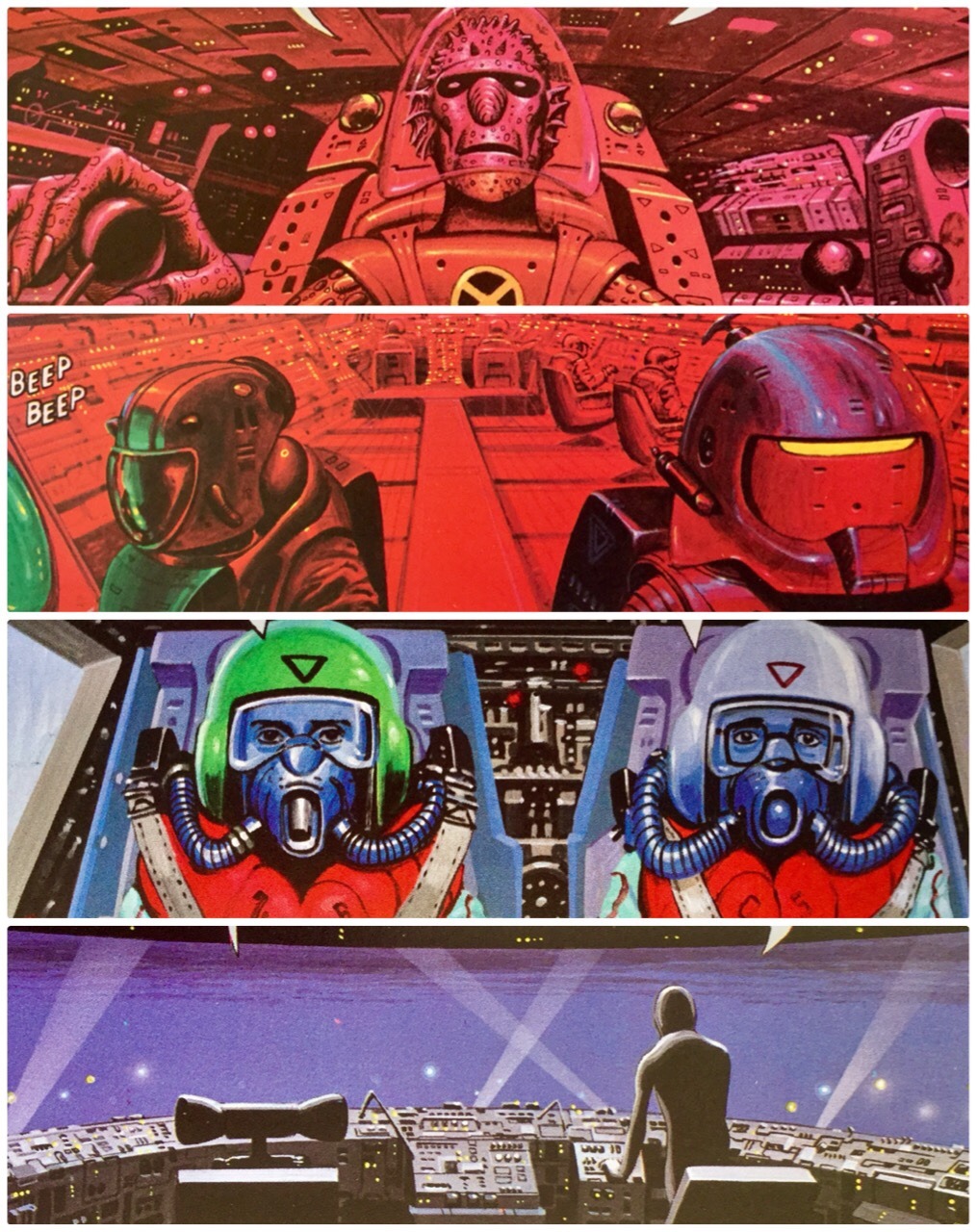

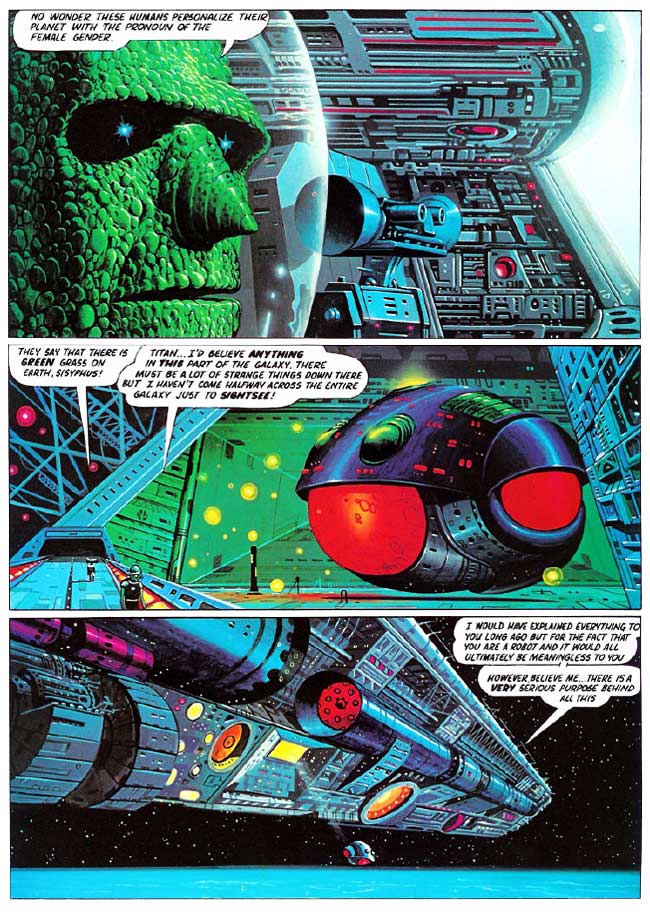

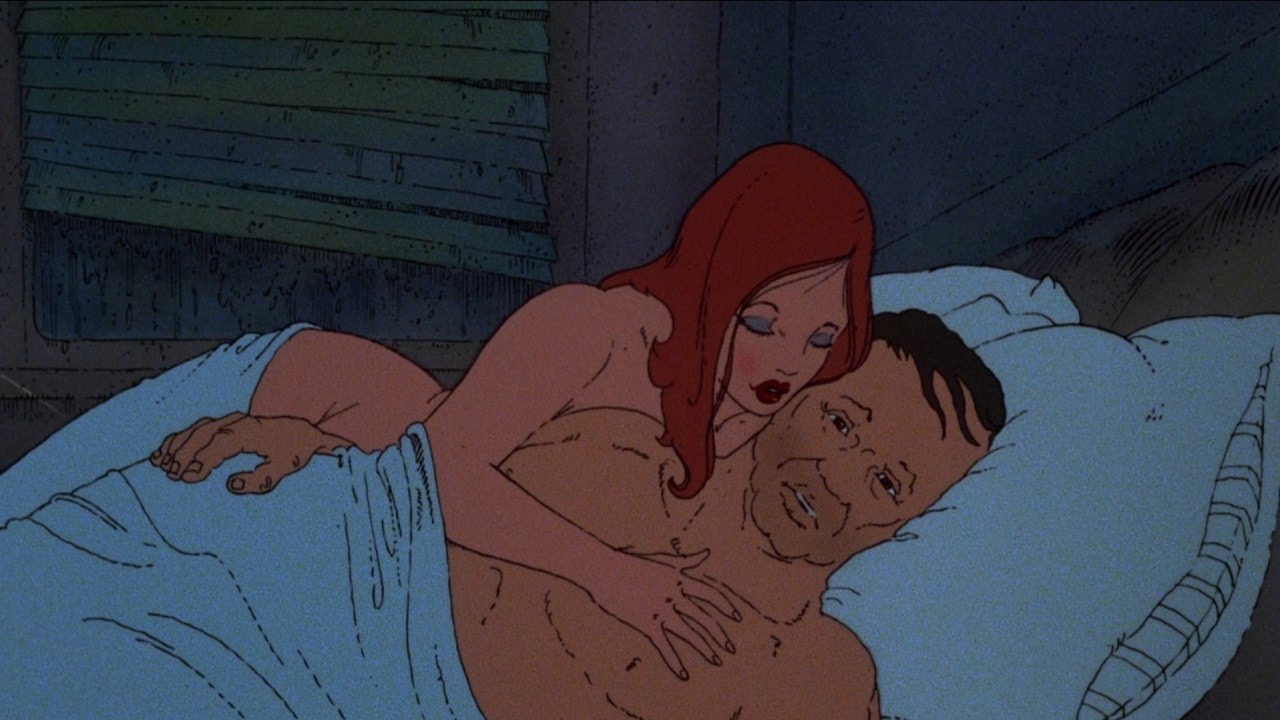

It goes something like this, as one scriptwriter, Len Blum, puts it, “from one universe into another.” It opens with the “Soft Landing” sequence, based on art by Thomas Warkentin, from an idea of Alien scriptwriter Dan O’Bannon [originally published in the Sept. ’79 Heavy Metal]. After this 2001: A Space Odyssey–like prologue, it shifts rather handily into the quasi-mystical “Grimaldi” story—the key linking device be-tween sequences. From this intro we jump into “Den,” the adaptation of Richard Corben‘s brilliantly drawn quintessential hero fiction, which ran during HM‘s first year. It presented the greatest challenge to bring to the screen. Corben’s spectacular color values were carefully maintained in the backgrounds, with bizarre expanses glowing in rich, fluorescent hues. The tale of young Dan’s transformation into the hero Den, who’s caught in the power struggle between the sorcerer Ard and the queen-priestess, is told with two near-explicit sex scenes amidst lots of solid, hand-to-hand combat.

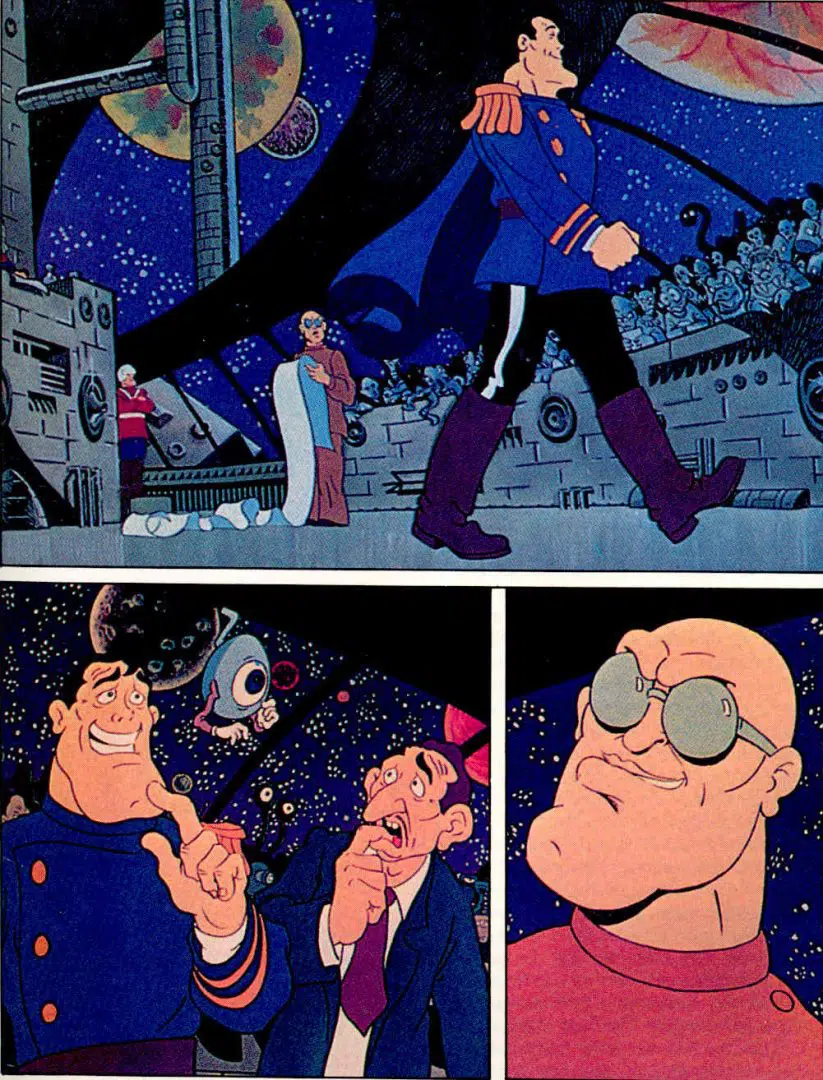

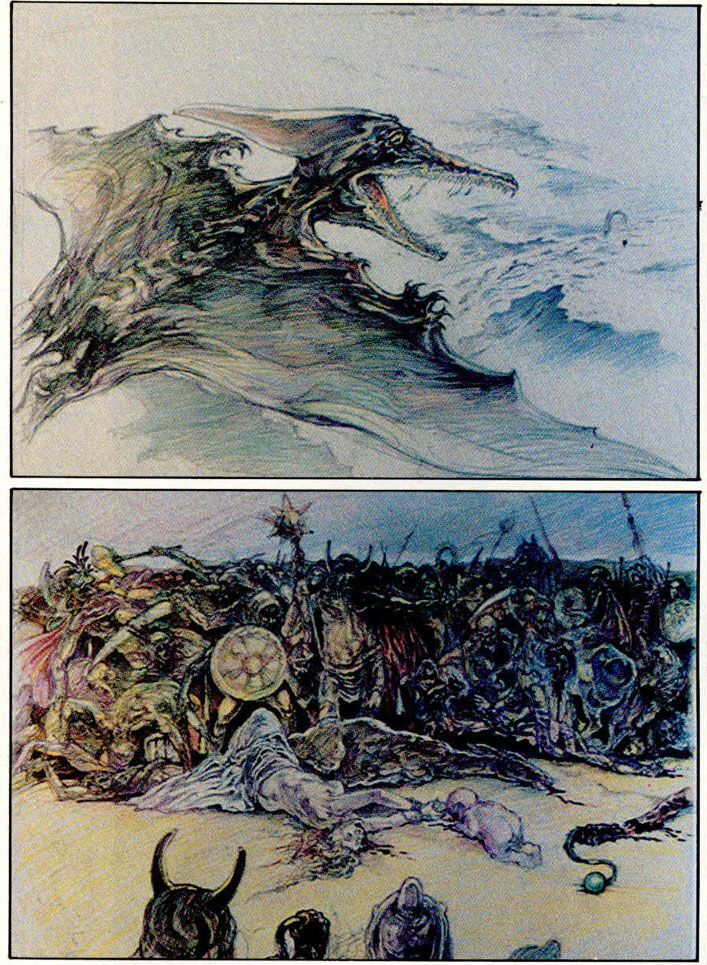

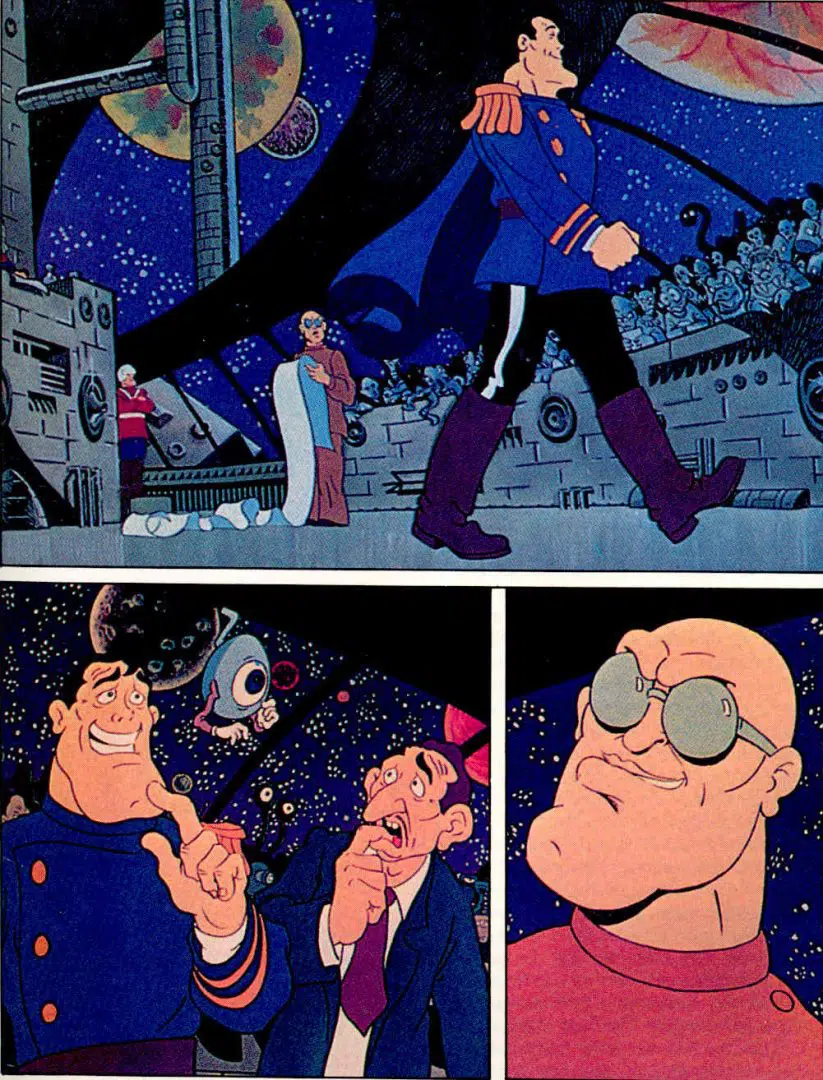

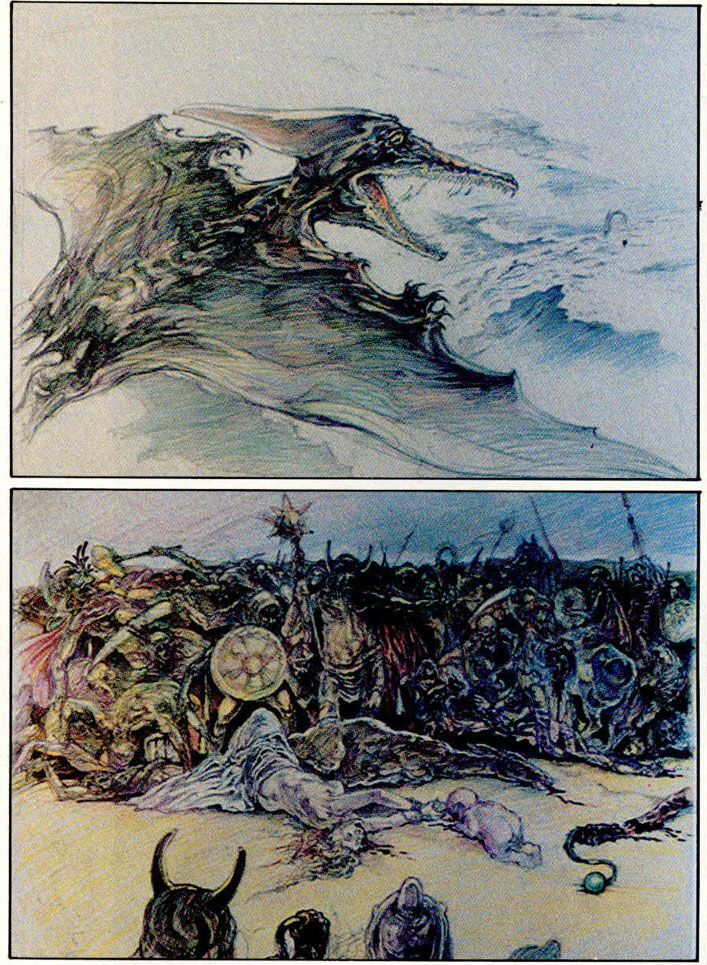

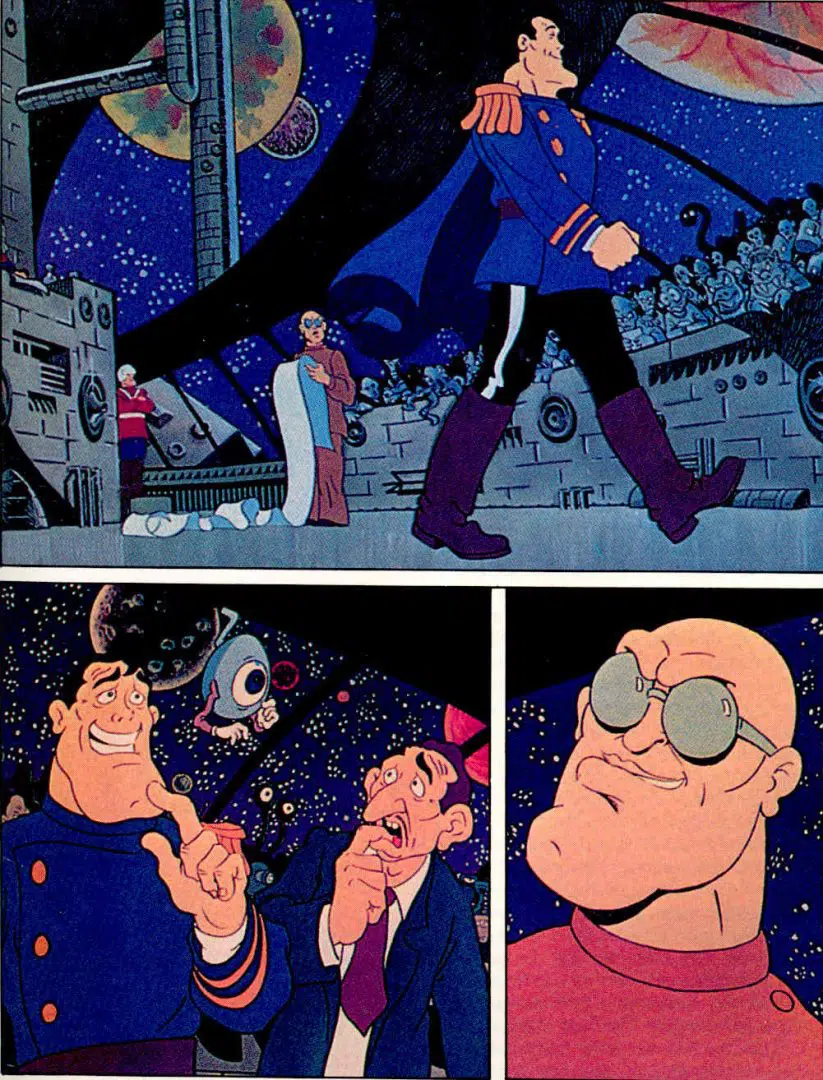

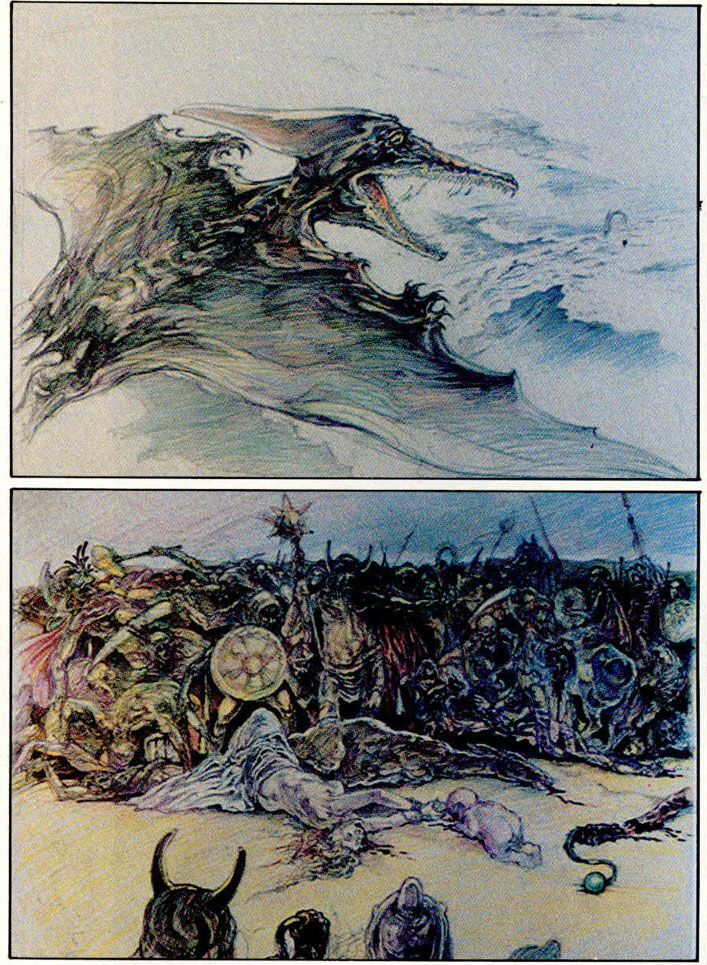

From these staggering visuals, the film carries us into the galactic court where Captain Sternn is on trial. From comic-artist great Berni Wrightson‘s original story [published in the June ’80 HM], Sternn is the ultimate parody of every space-opera villain-hero. Says artist Wrightson, “I’ve always had trouble writing something serious. So when Captain Sternn grew out of Star Wars—I was never an SF fan until I saw it—as a funny adventure, it degenerated into a broad farce. I was also inspired by Warner Bros. cartoons; hence I created his foil character, Hanover Fiste.” As the story leaves the conclusion of the trial, it moves into the “Neverwhere” world—master animator Cornelius Cole’s personal vision of the history of evil as a basic force in history. Cole’s visionary graphics (intricate ball-point renderings of lyric pastels) get most viewers to say, “Holy shit, this stuff is really coming to life!” Says Cole, “You reach a point in animation where you must have the opportunity not to cut corners.”

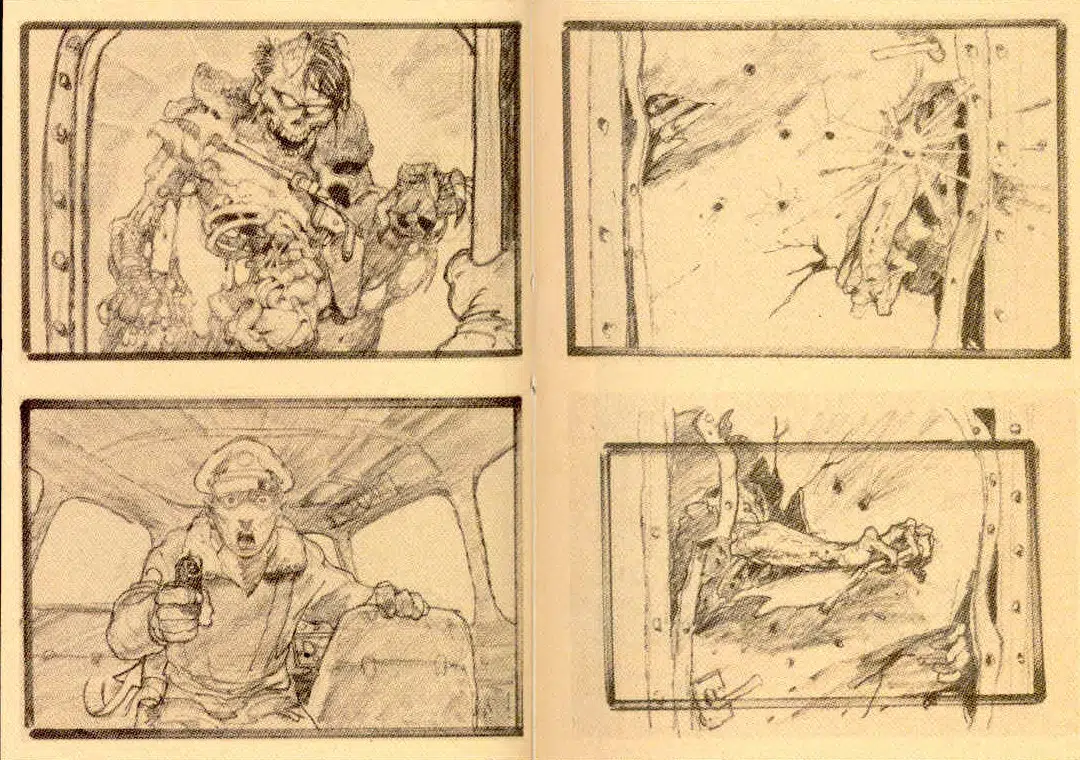

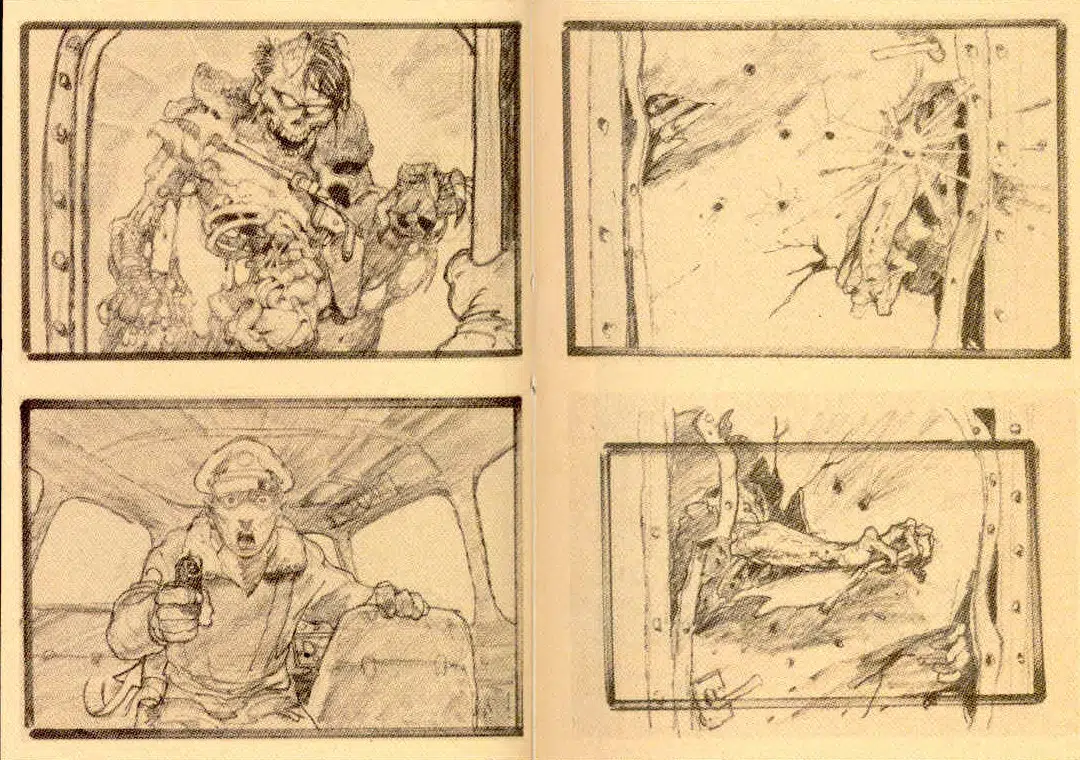

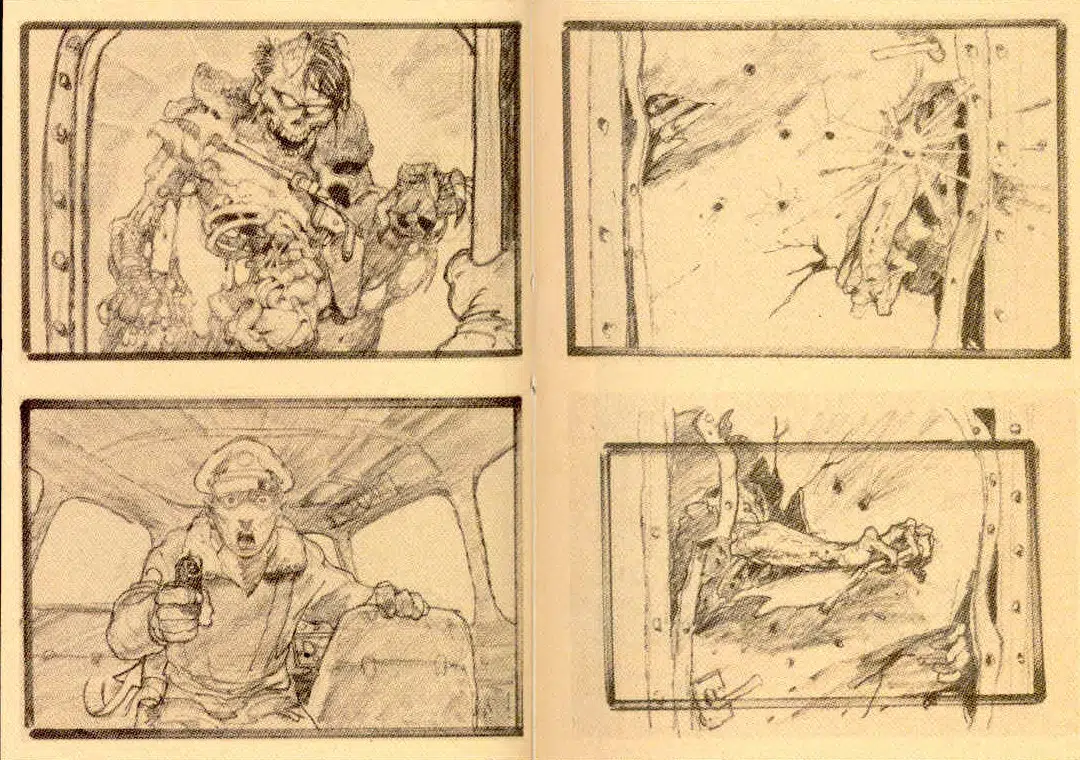

On to “B-17,” the first true horror story to be animated, with all the savagery that makes great shockers. Will Eisner–trained film artist Mike Ploog did most of the conceptualizations. His background as a former Marvel Comics “Conan” and “Frankenstein” artist lends greater power to this 1950s E.C. Comics–style terror tale. A favorite of producer Reitman’s since he was an E.C. collector as a kid, the story (based on an original idea of O’Bannon’s) was given a twist of authenticity. They visited an aviation museum, and one of the last few flyable B-17s was flown in order to record actual sound effects of the plane. Coincidentally, the HM animation team includes three WWII bomber crew-men, several licensed pilots, an ex-RAF inductee, and a director who collects aviation memorabilia.

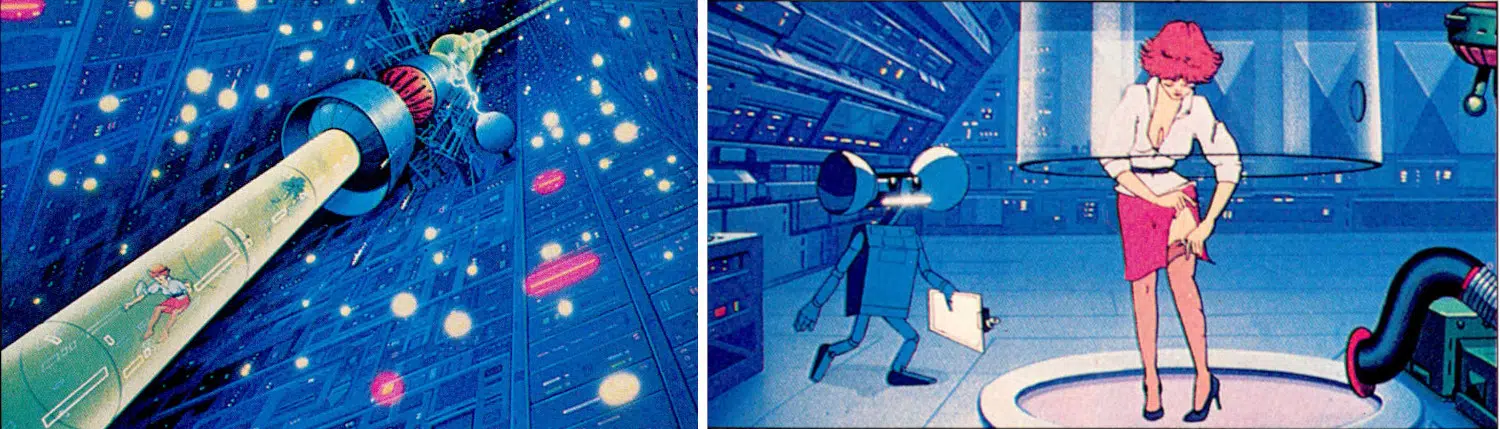

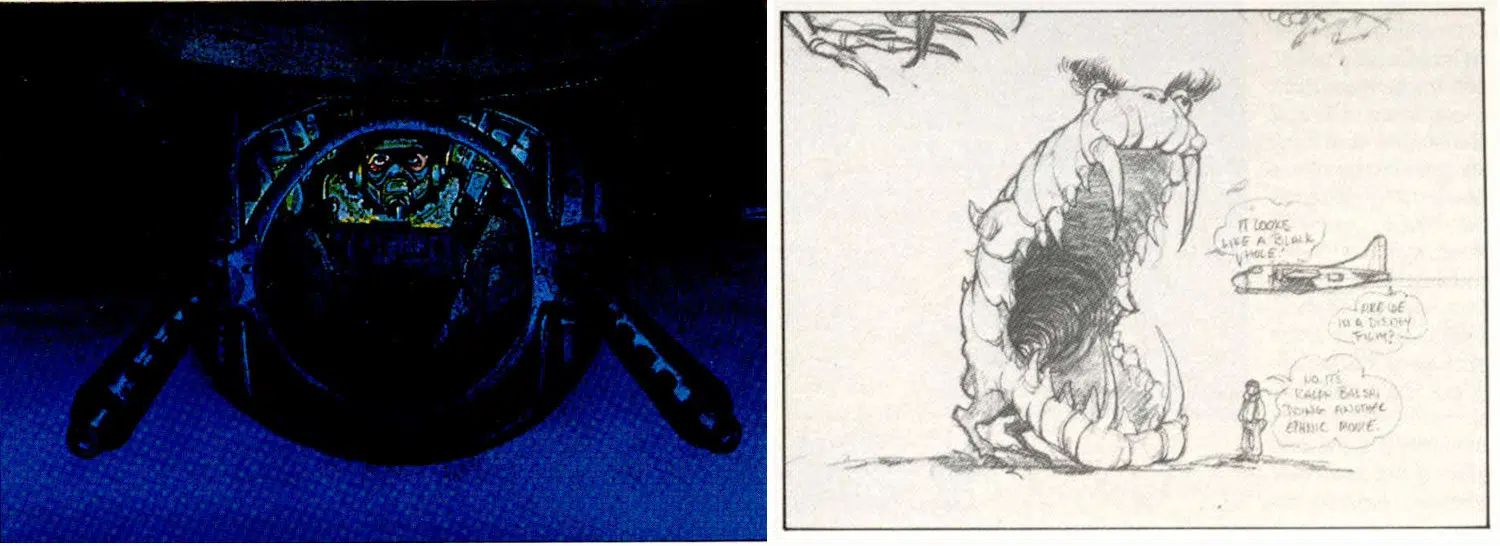

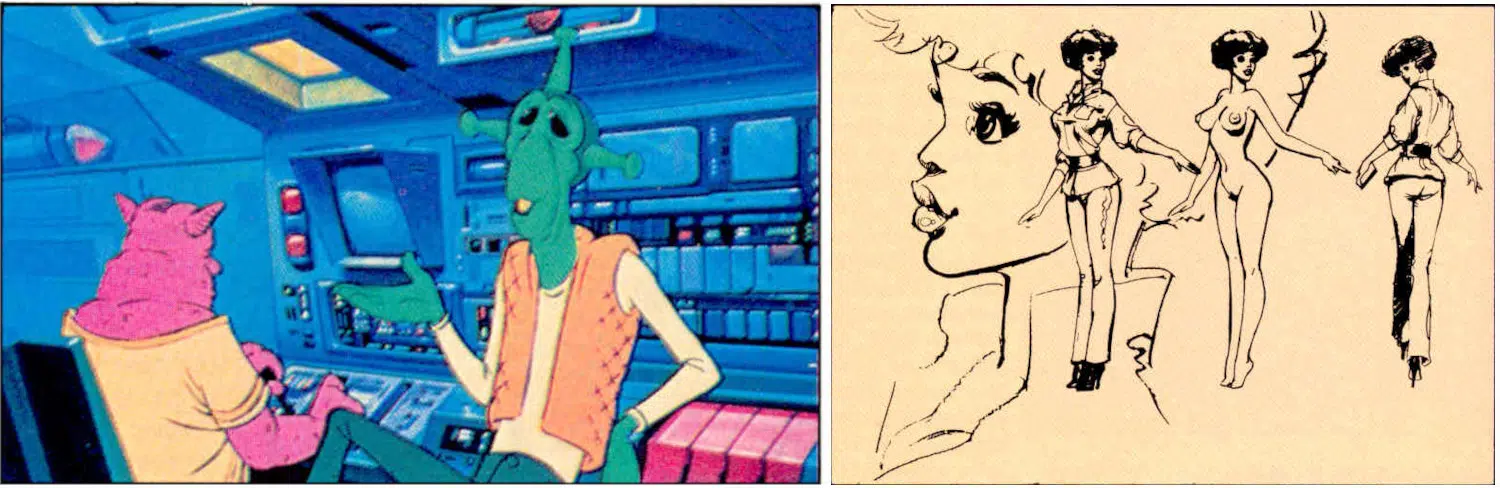

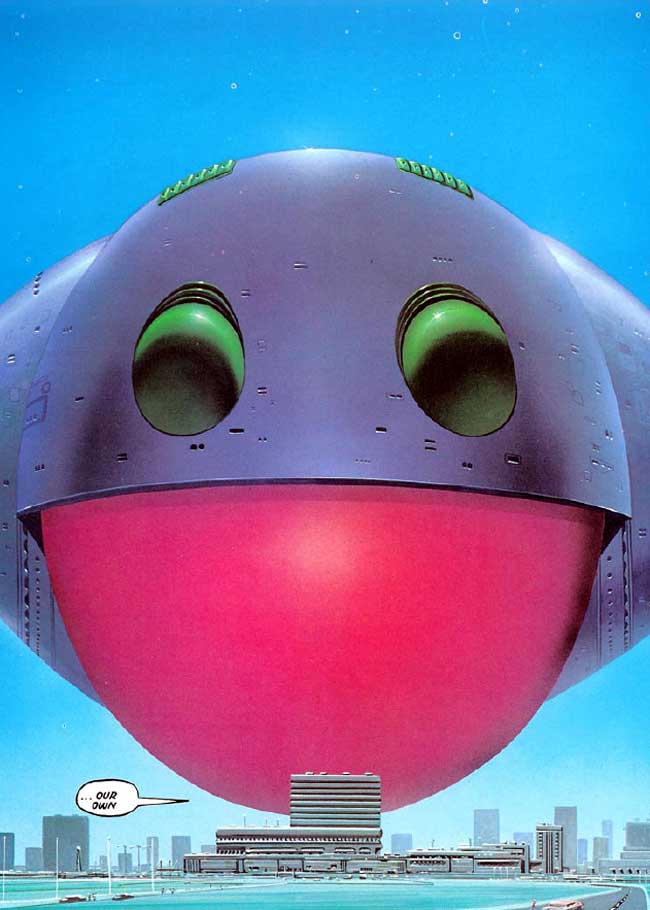

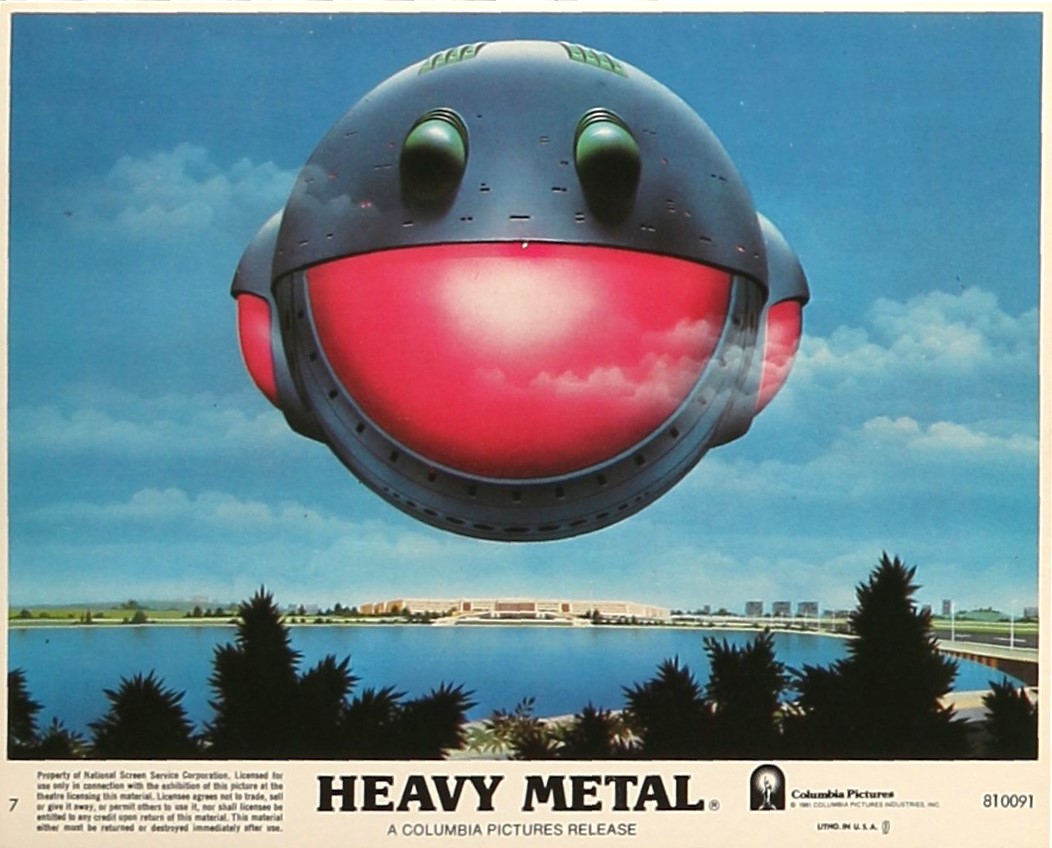

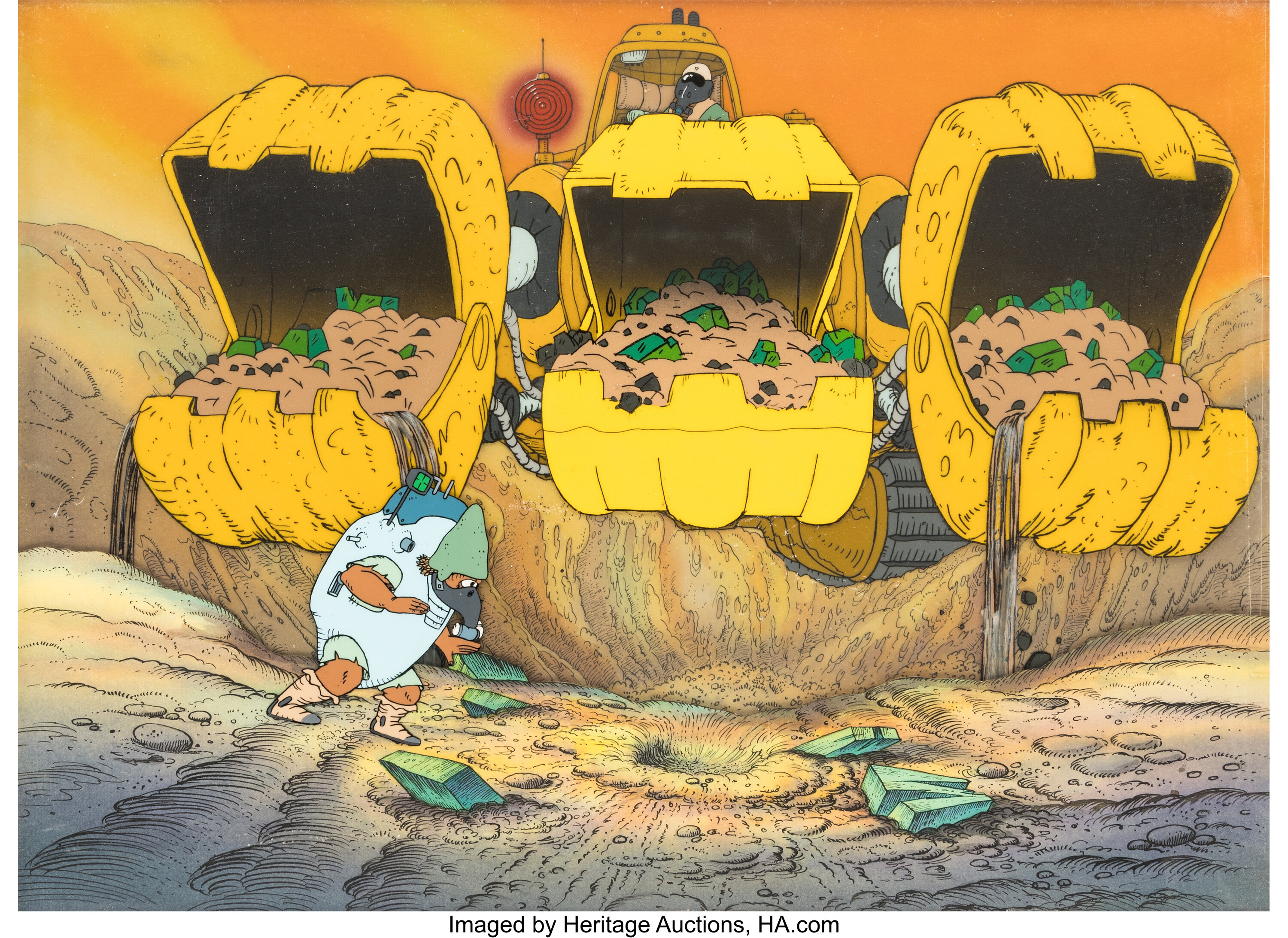

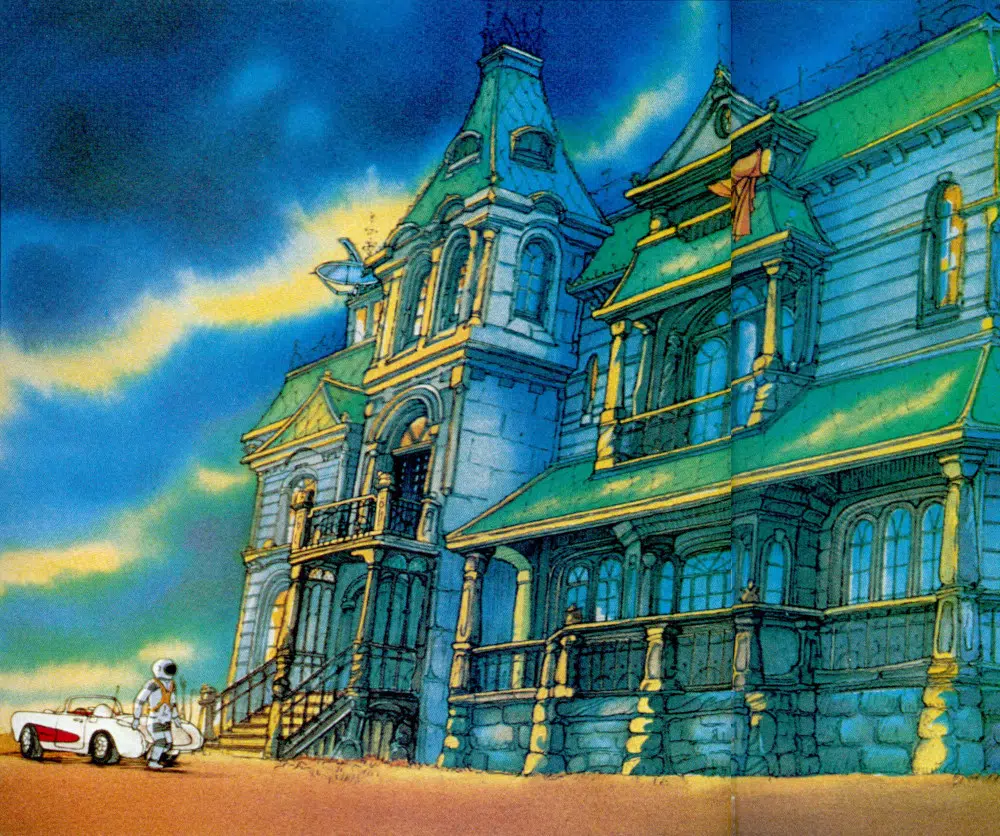

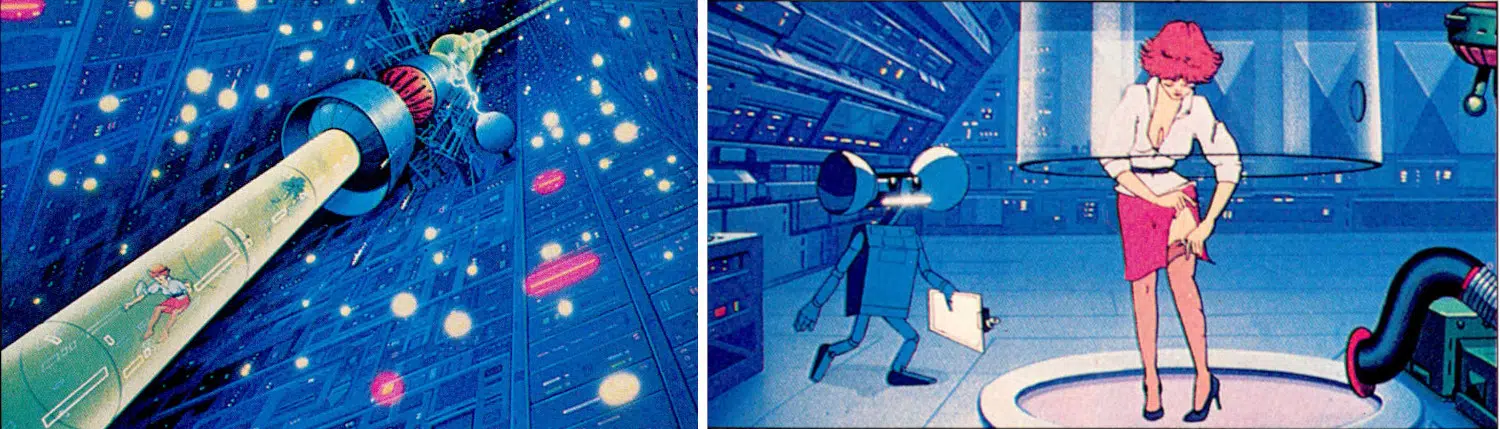

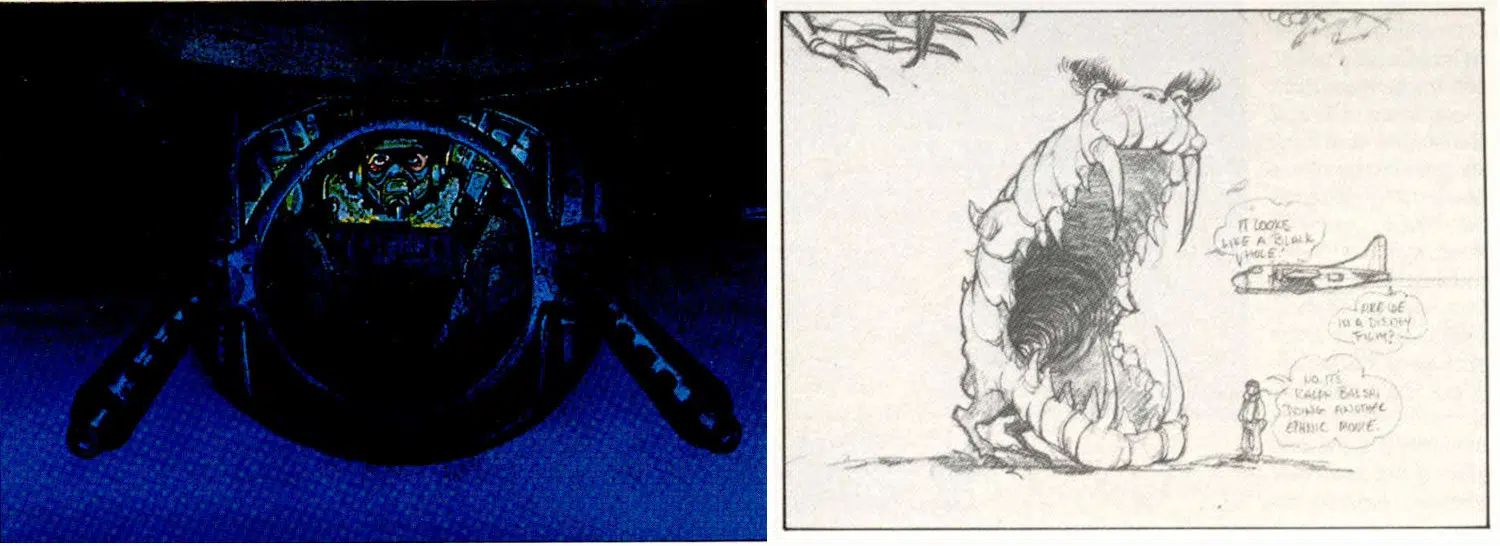

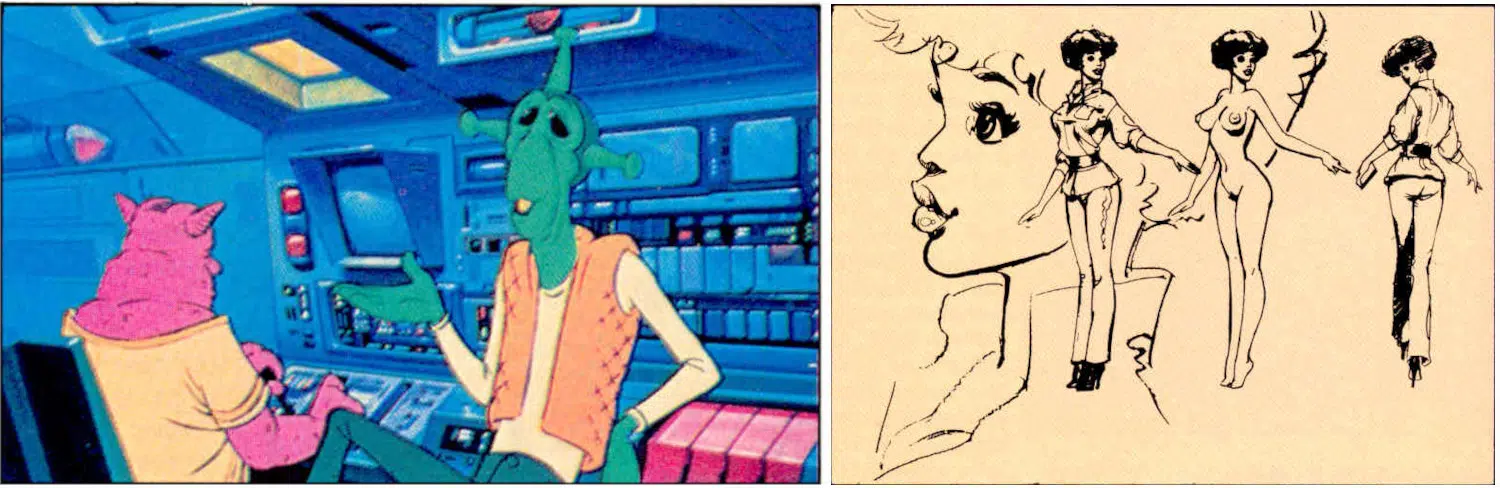

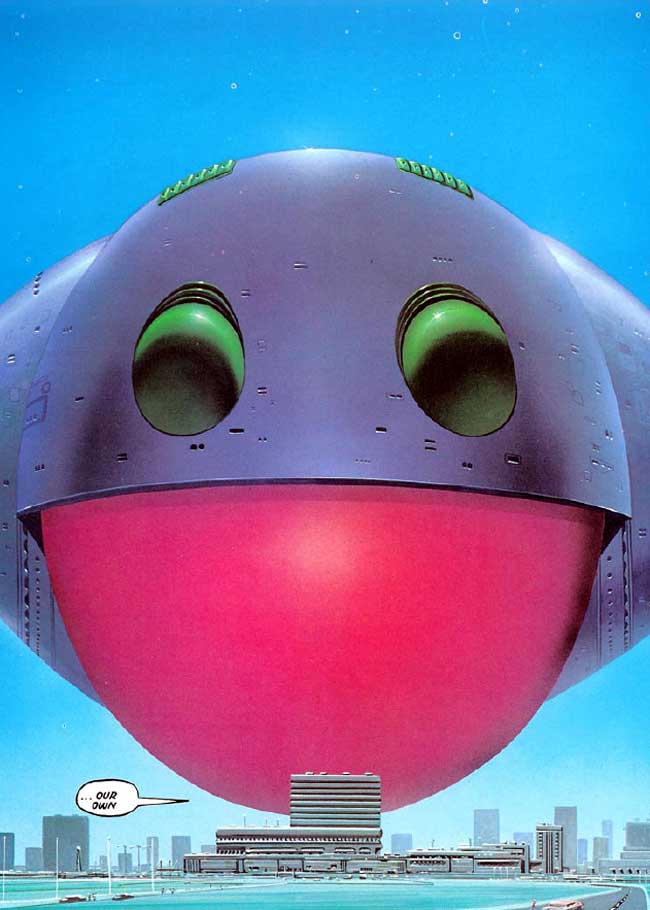

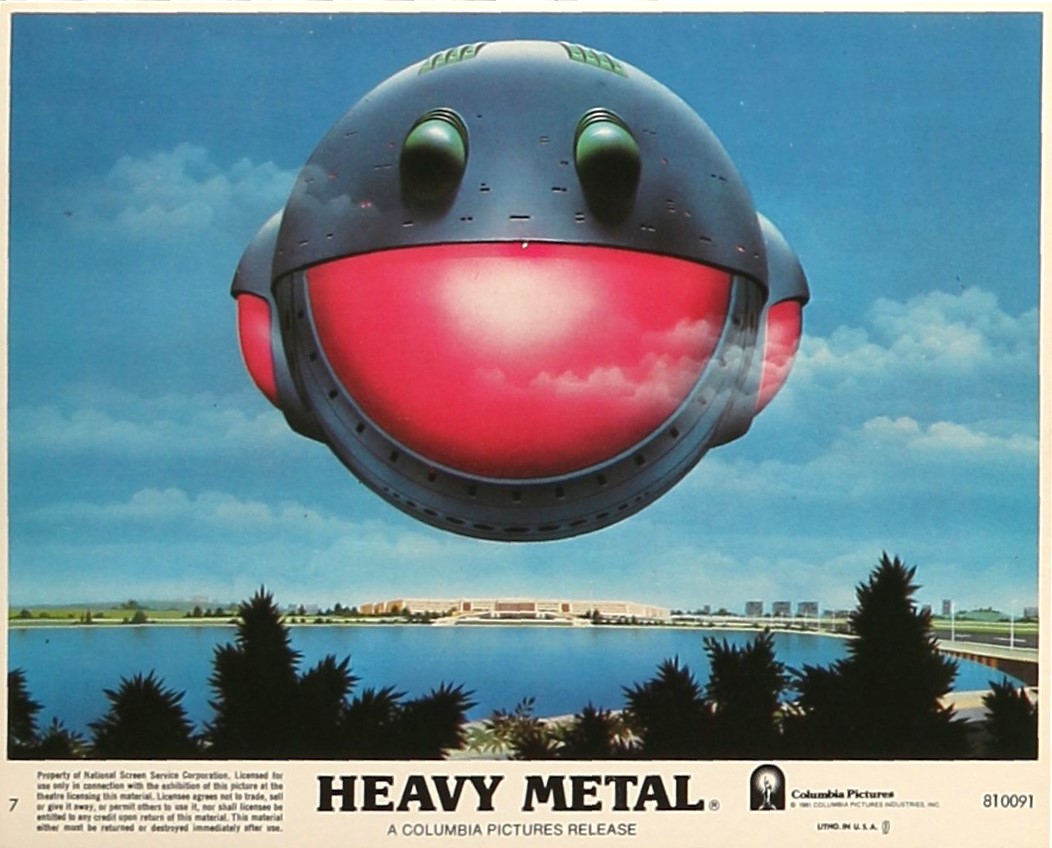

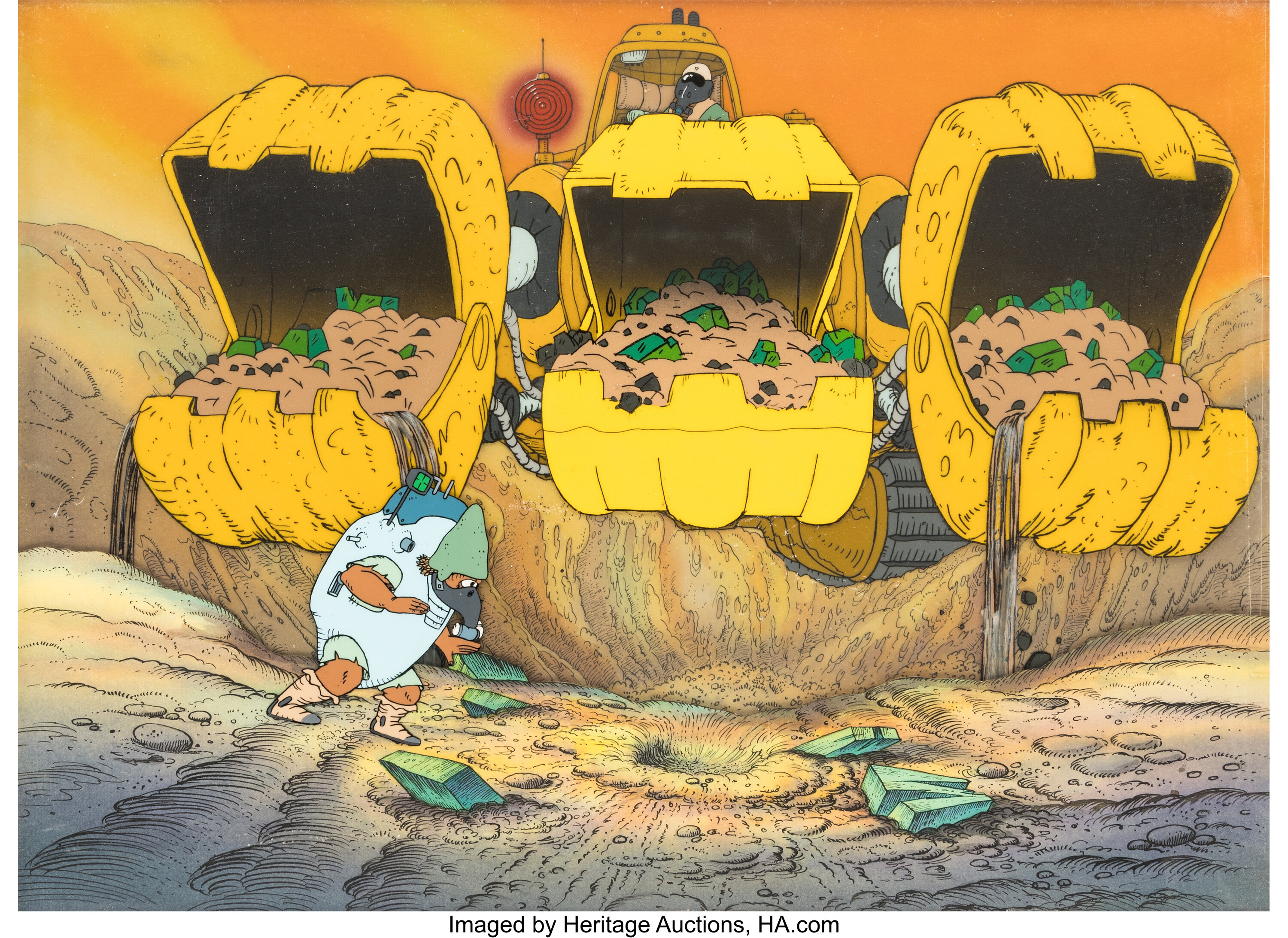

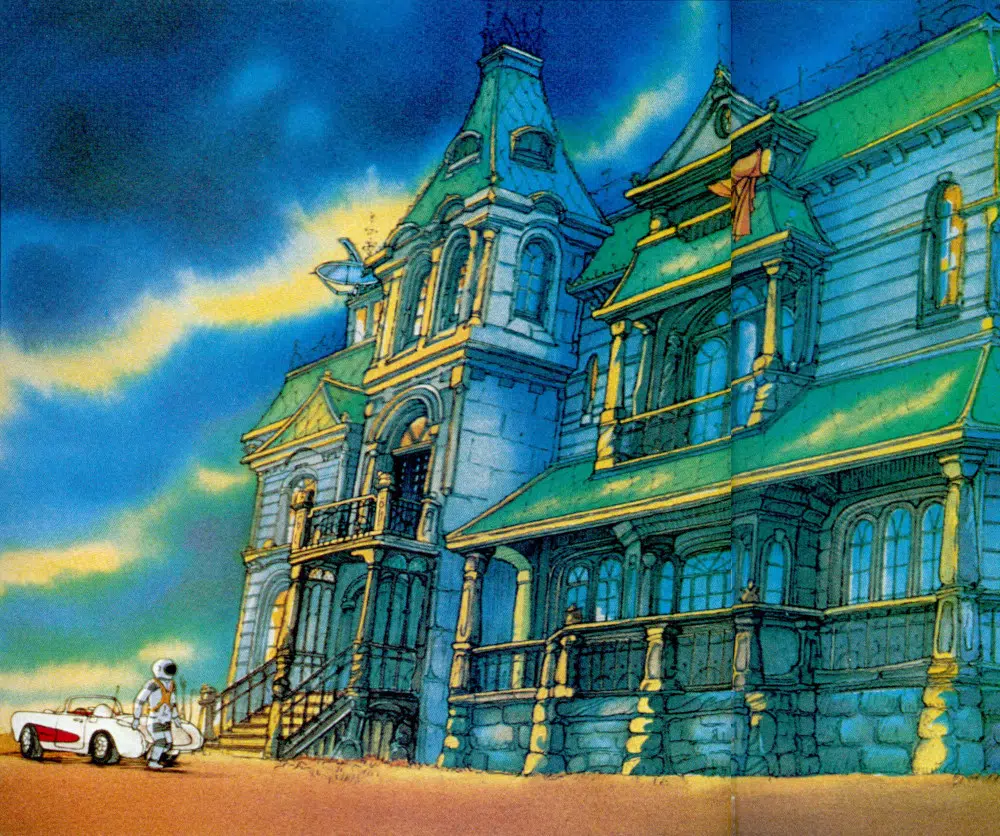

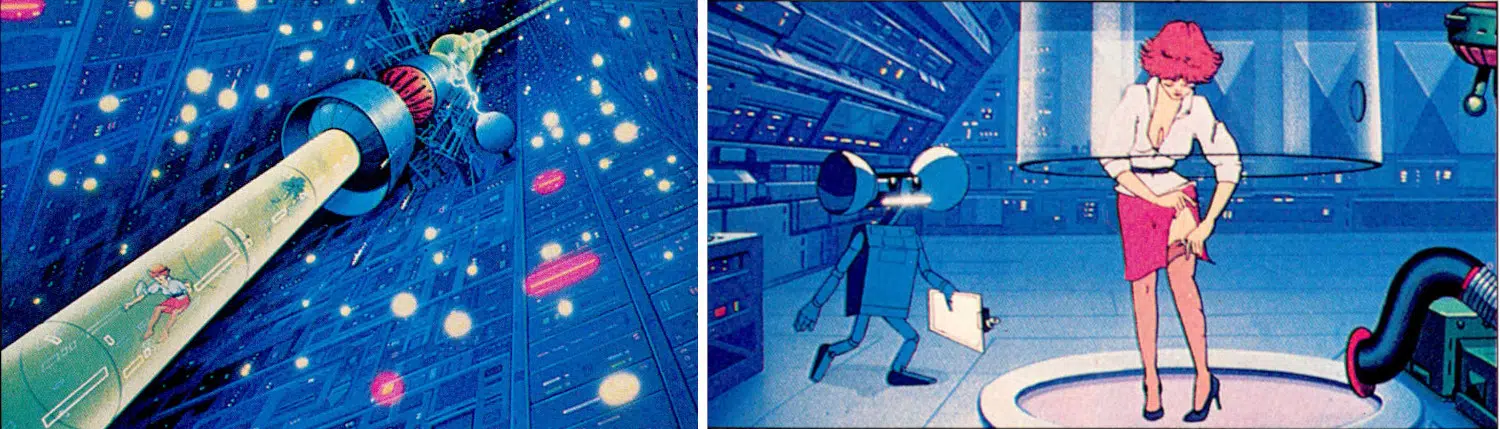

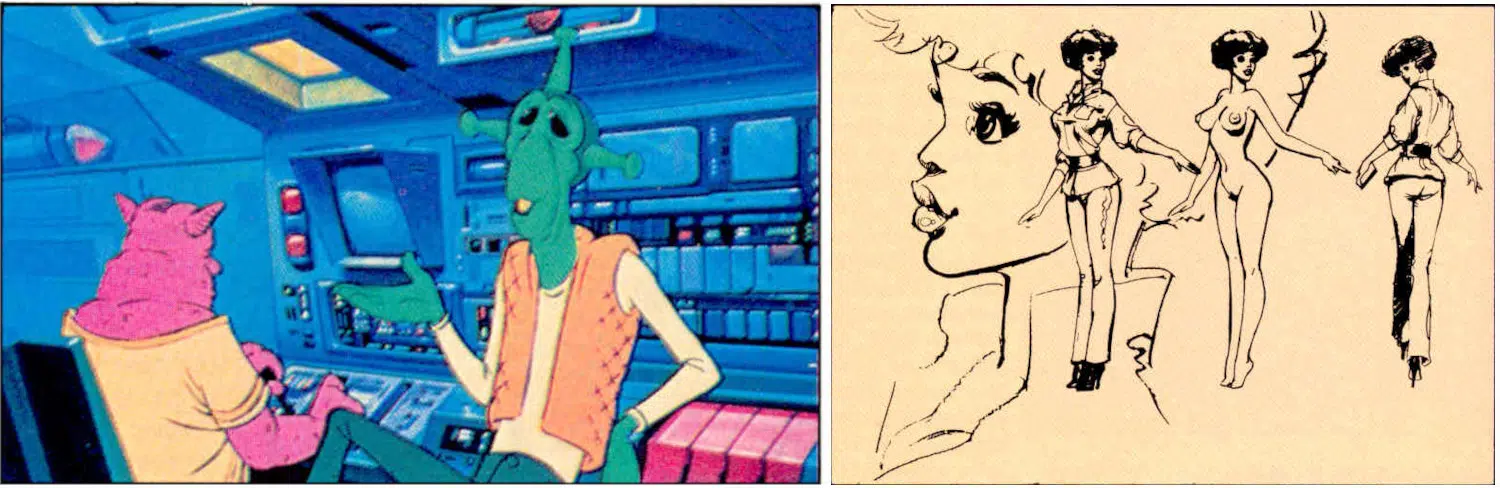

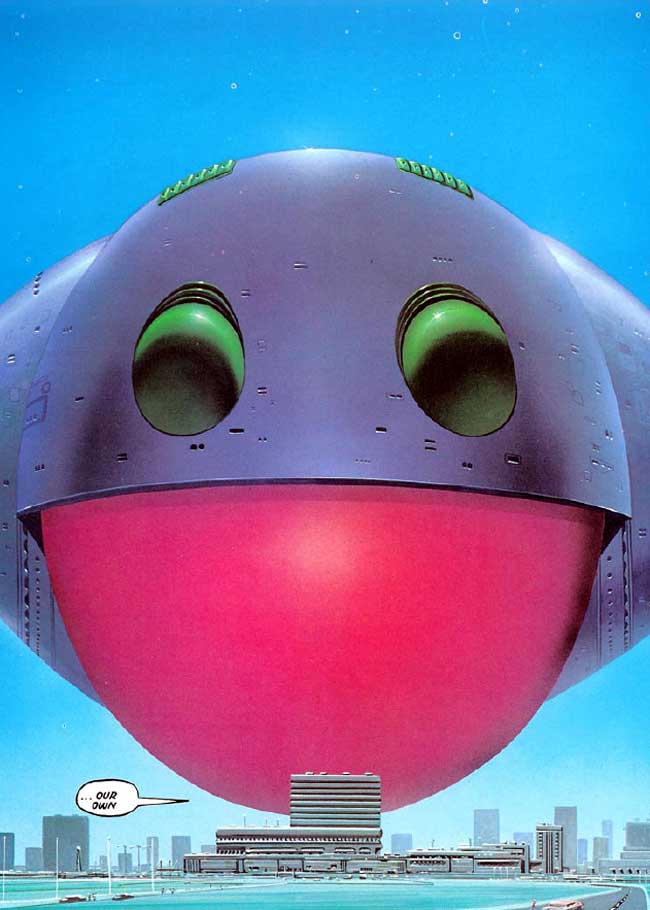

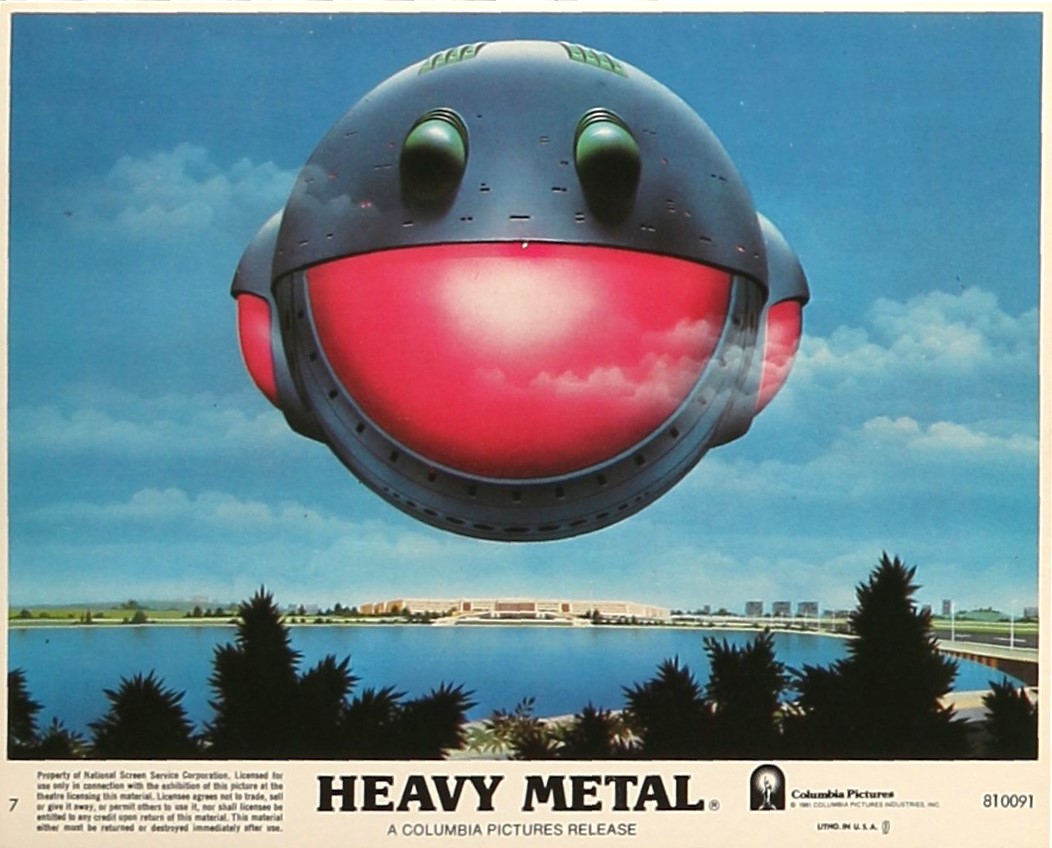

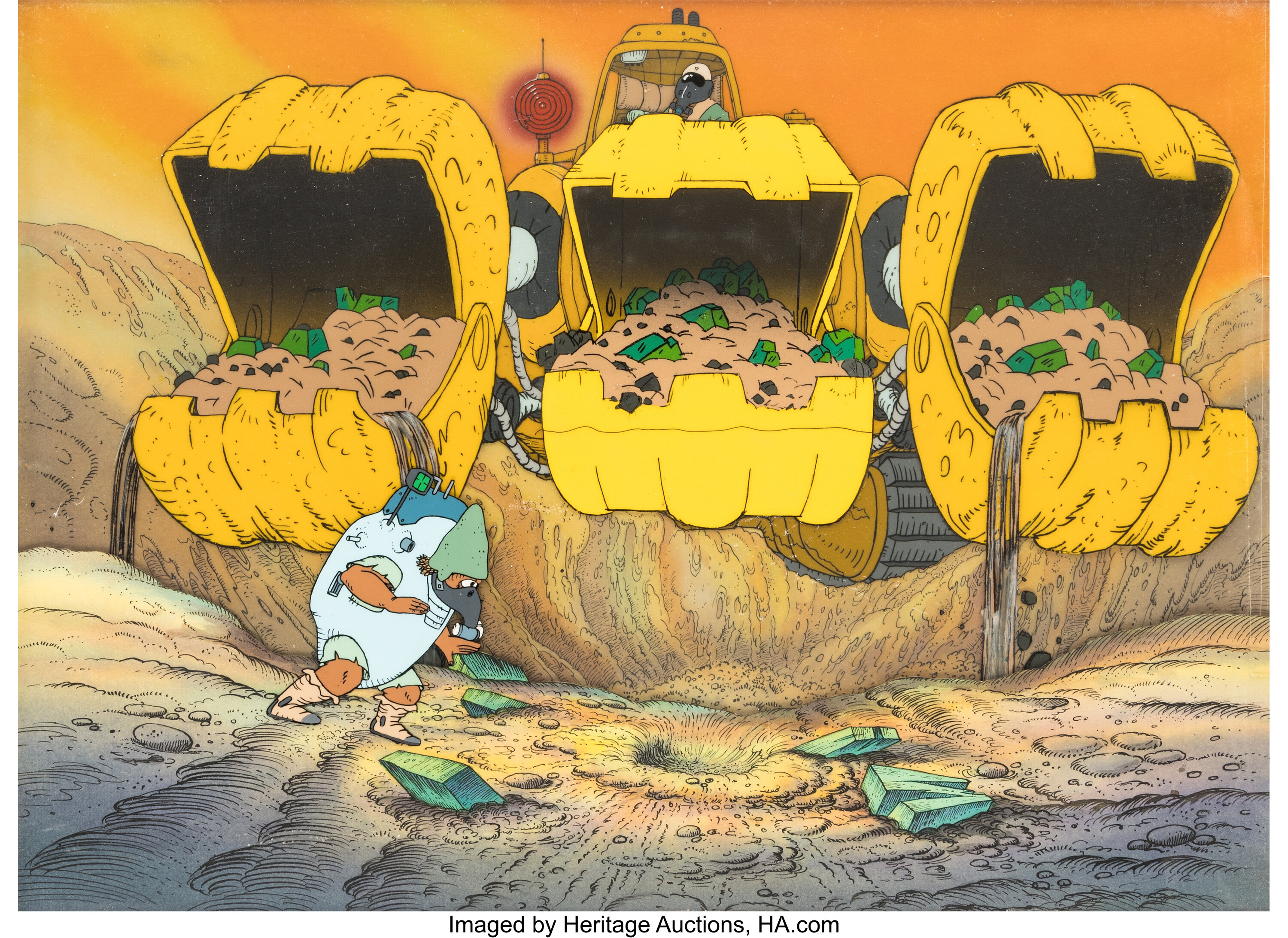

With the following sequence, “So Beautiful and So Dangerous,” came the original artist, Angus McKie, who illustrated the serial in HM, which later became a book. He directly contributed 70 key background paintings of the most incredible animated sequences ever done. The contrast between McKie’s high-tech environments and the three space jockeys (well, two, and one robot) are inspired by Cheech and Chong. There are lots of outer-space drug references and some interstellar sex.

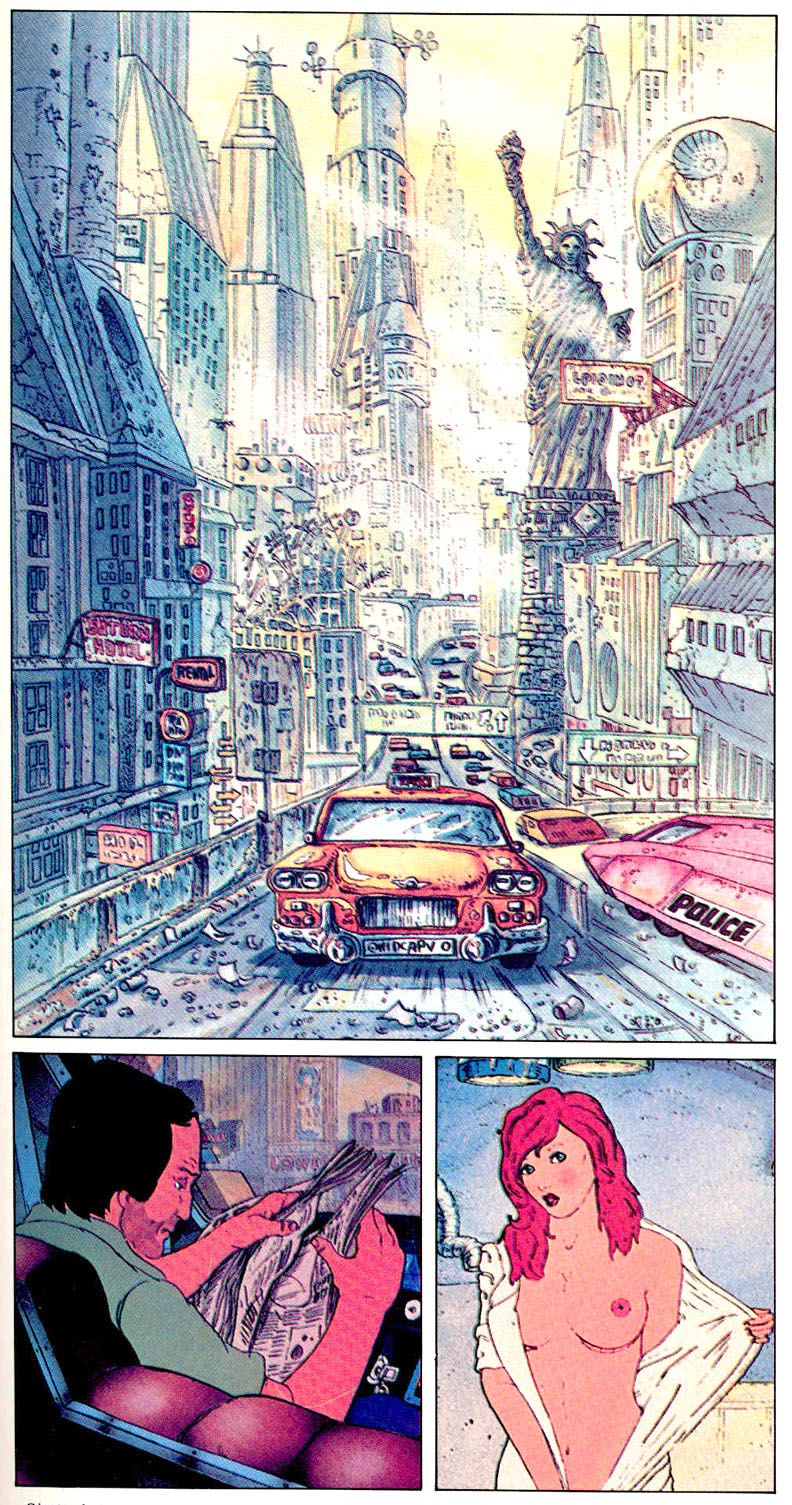

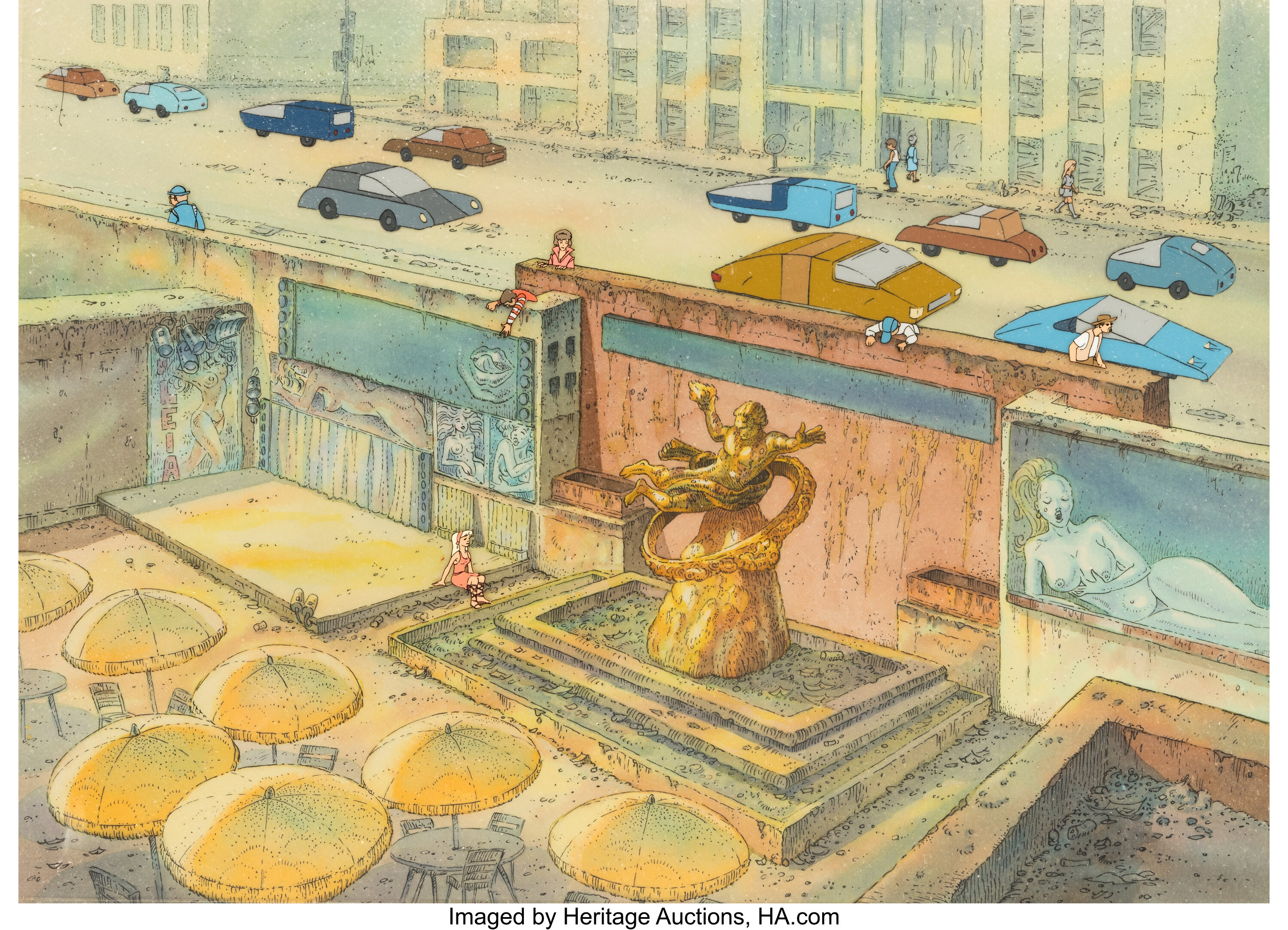

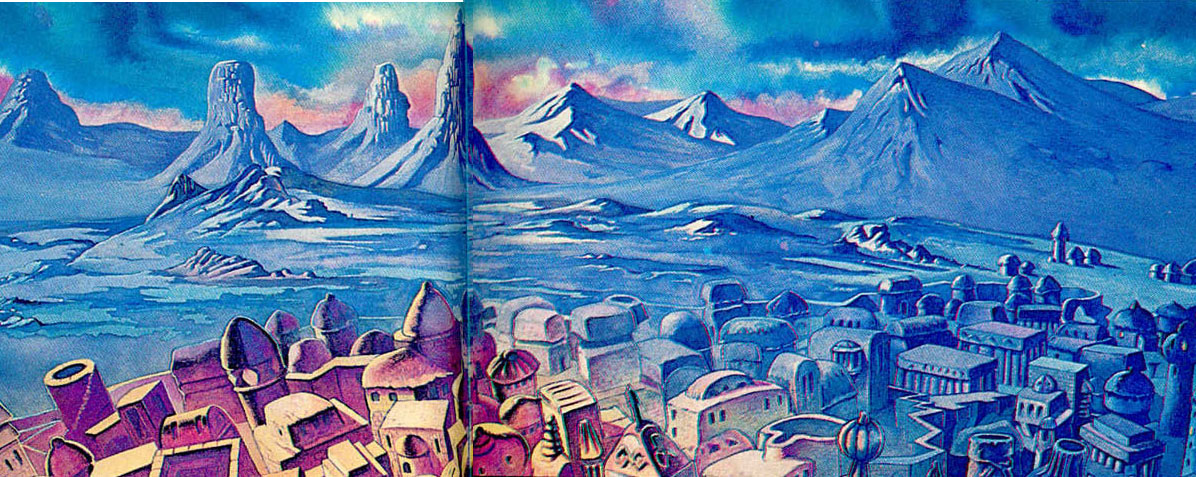

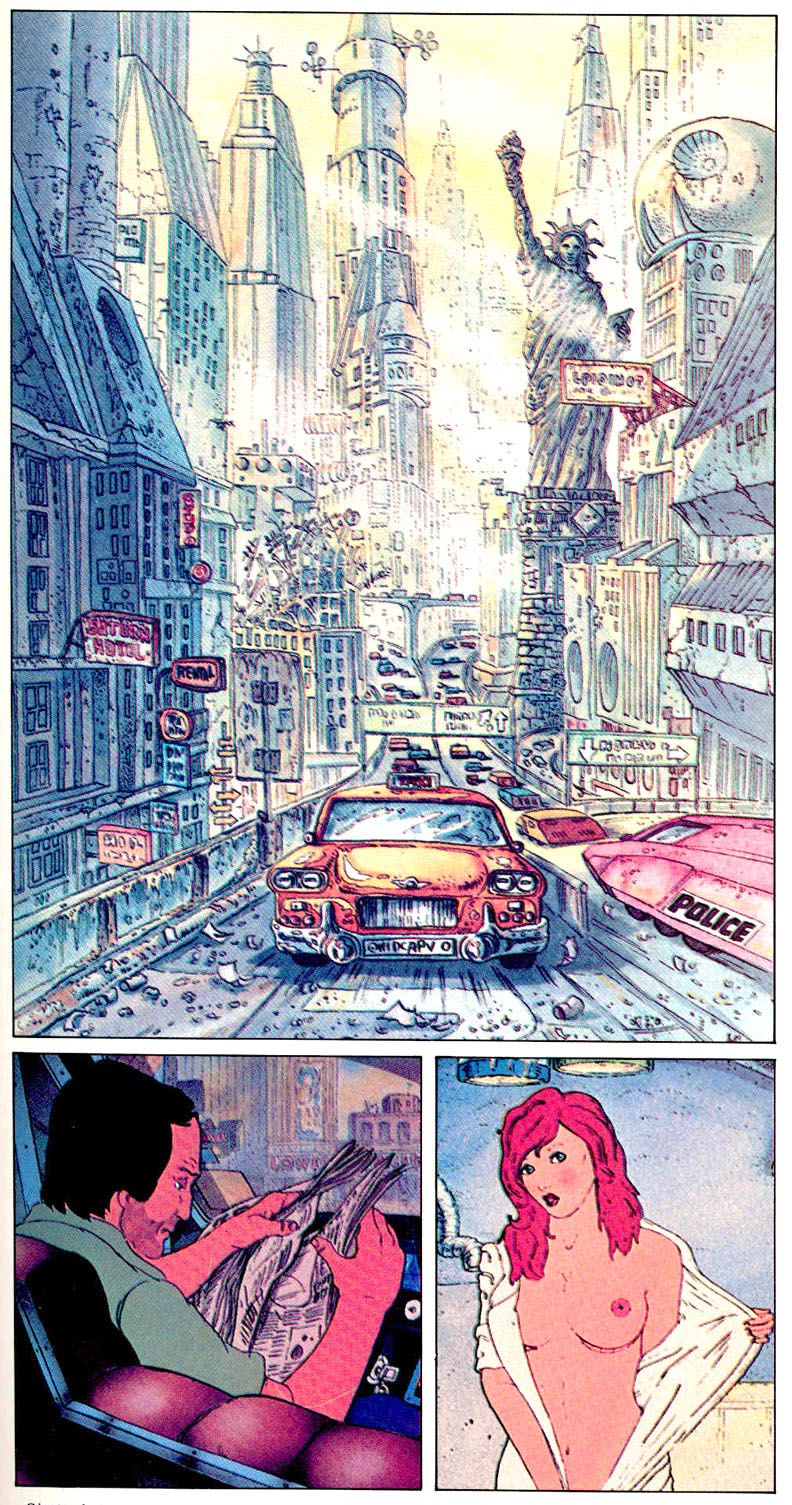

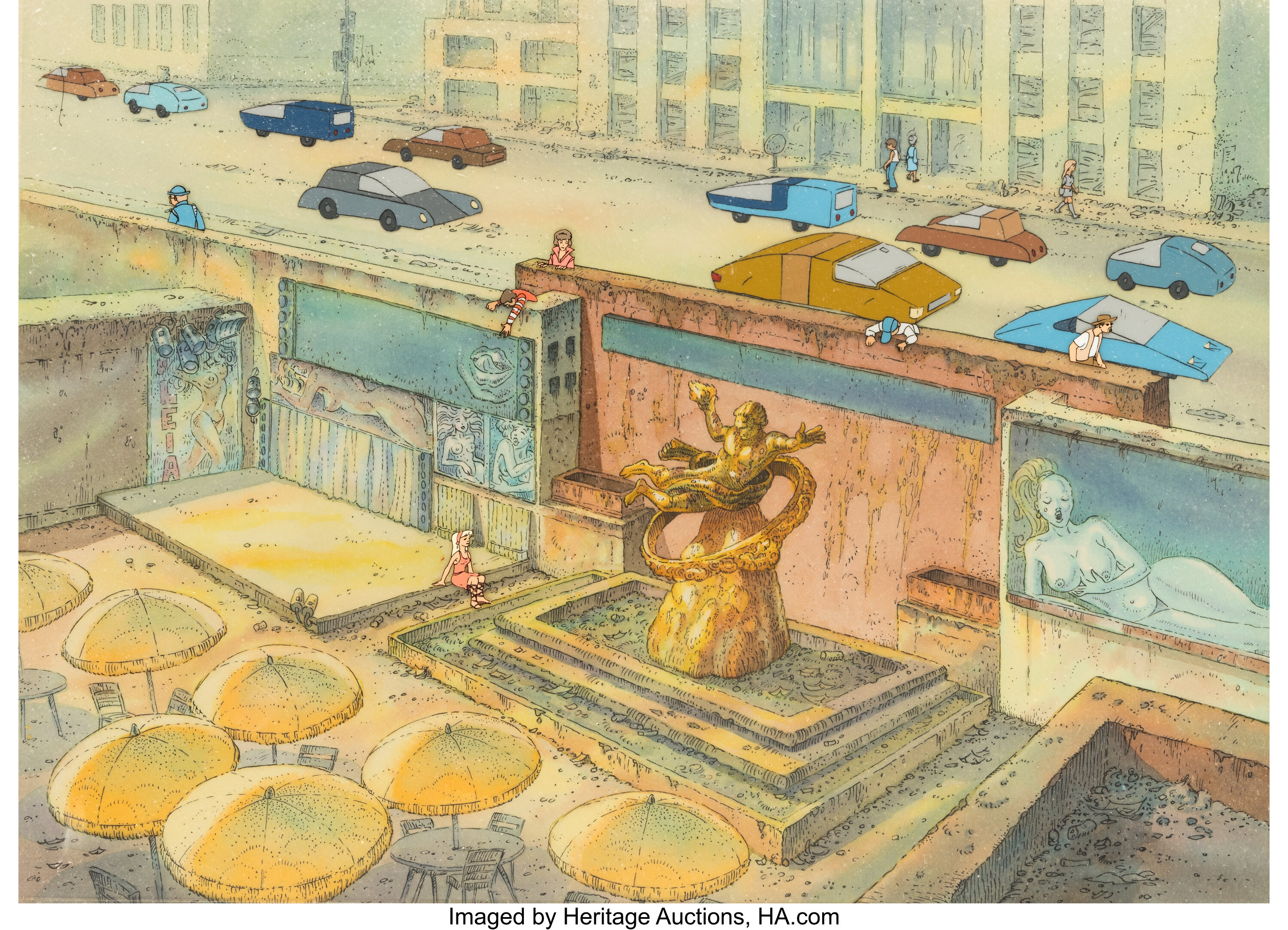

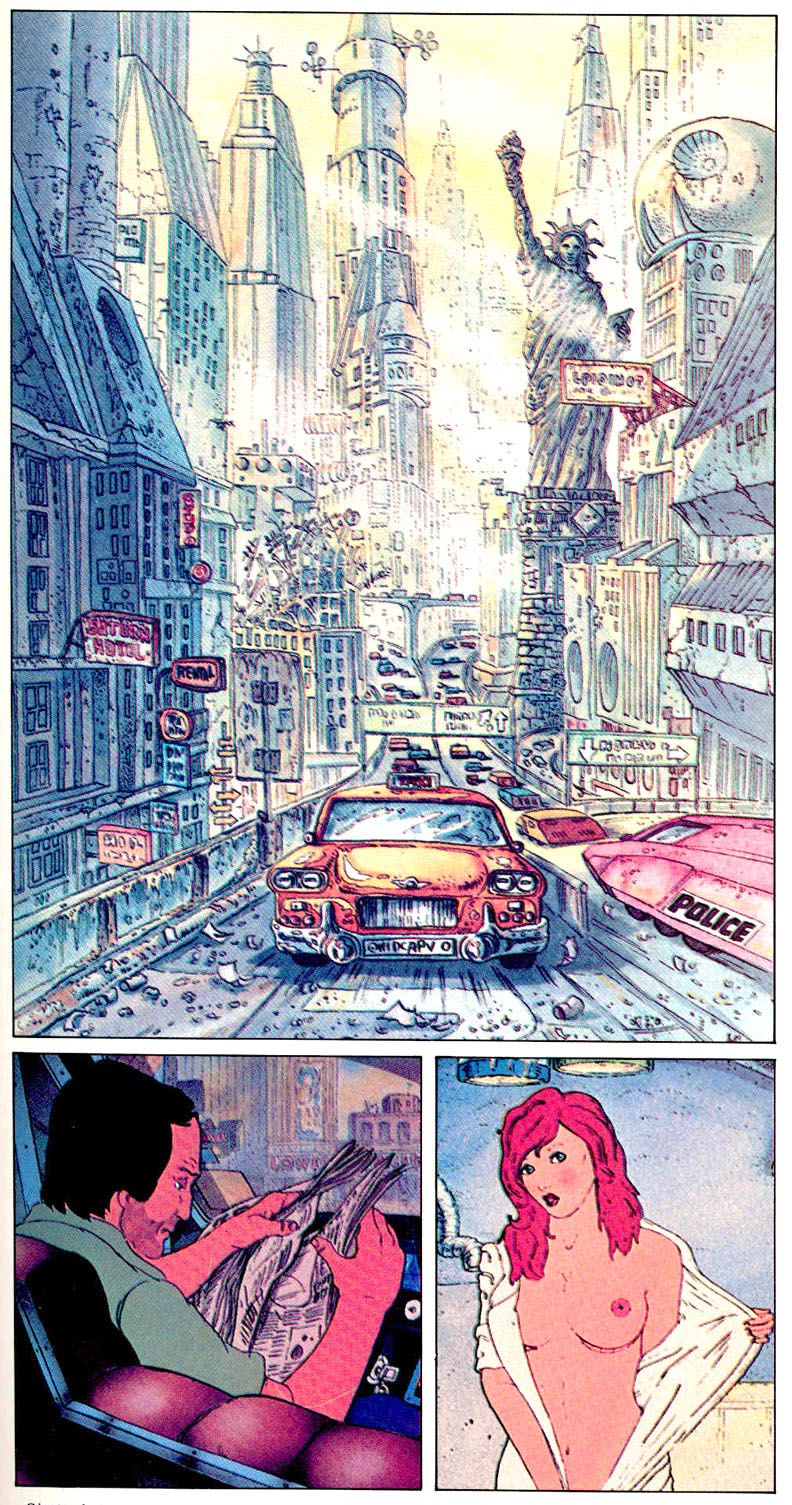

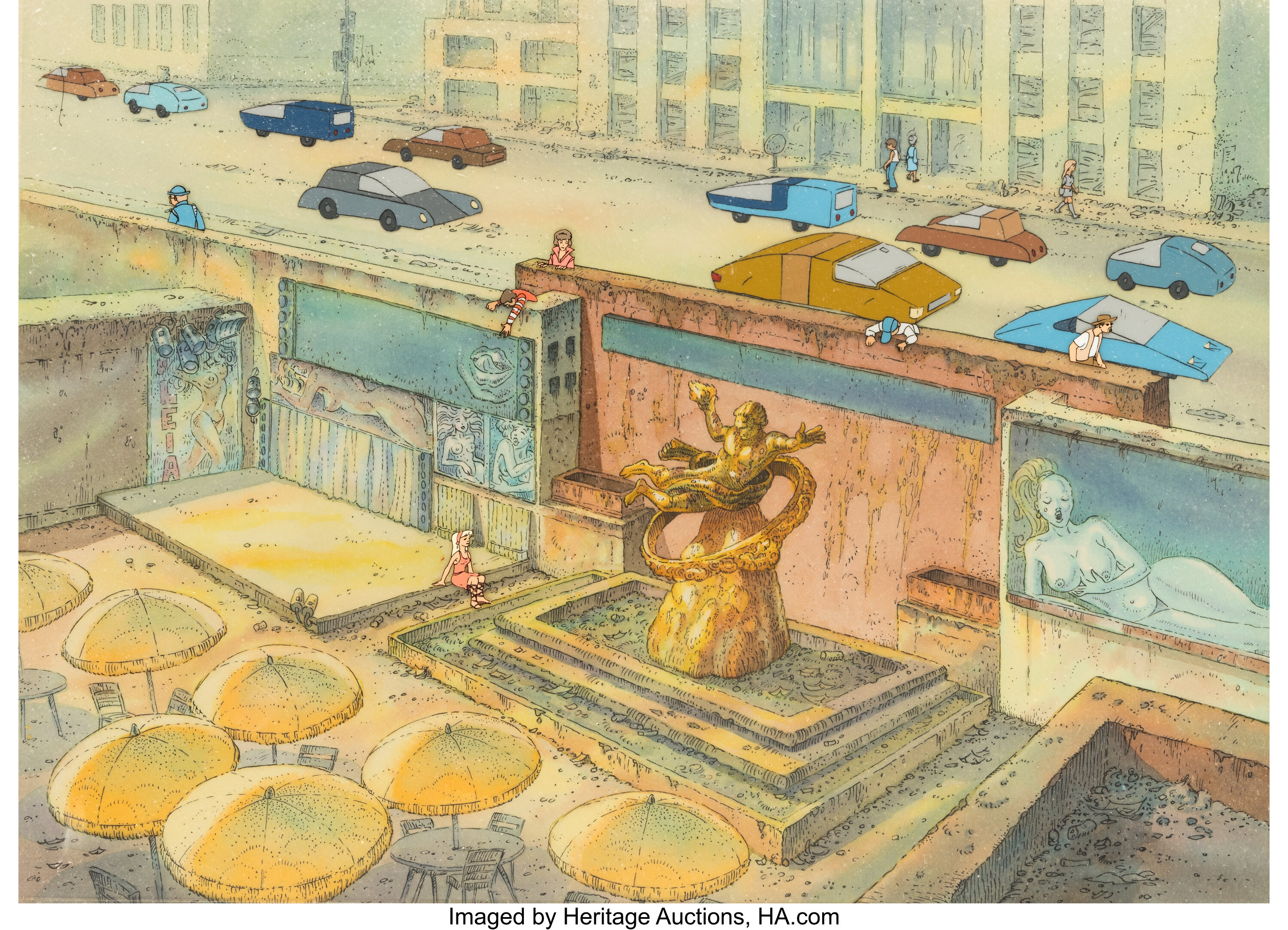

Gimenez’s “Harry Canyon” is an original depiction of a world half-familiar—New York City—in an unfamiliar time, 2031. The misadventures of a cynical cab driver caught in the middle of a battle for valuable stolen goods comes right out of a thirties detective story. “We sort of thought of it as an animated variation of Dashiell Hammett’s Maltese Falcon, starring Humphrey Bogart,” says the other scriptwriter, Dan Goldberg. This New York of the future is everything the current NYC is, only more: there’s Times Square with cheap, rip-off churches; a cop station that charges to aid the troubled; a Statue of Liberty no longer in the bay but surrounded by skyscrapers; and a Brooklyn Bridge graced with the sign “Use at your own risk.” Ironically, all of this was initially envisioned by the exceptional South American illustrator Juan Gimenez, who had never visited New York when he did the subtle drawings. He imagined a New York City unprejudiced by its reality—a reality that he discovered only weeks after his four-month drawing stint in Canada. When brought to New York to visit the HM office he saw the Pan Am building and exclaimed, “It really does exist as I saw it!”

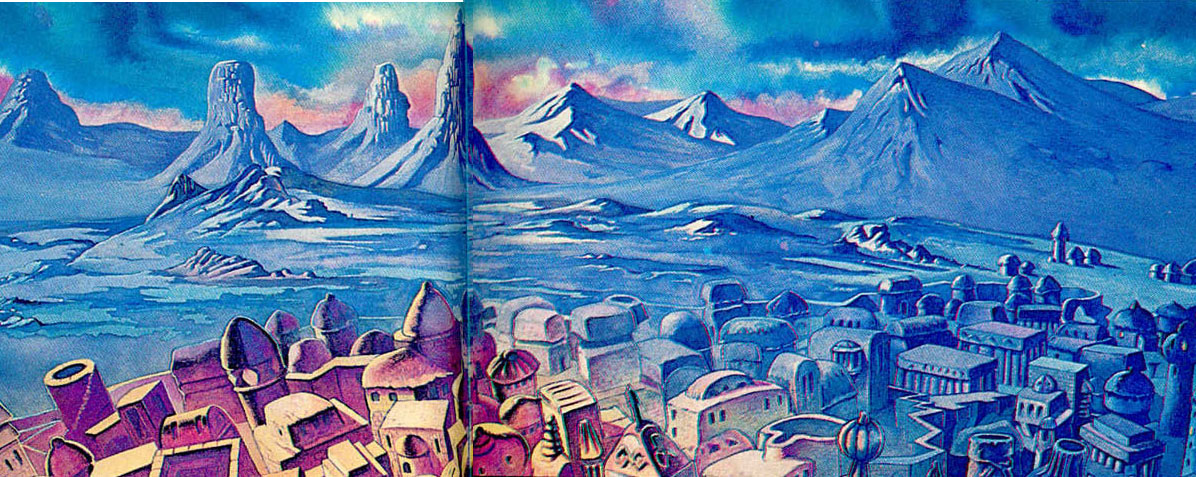

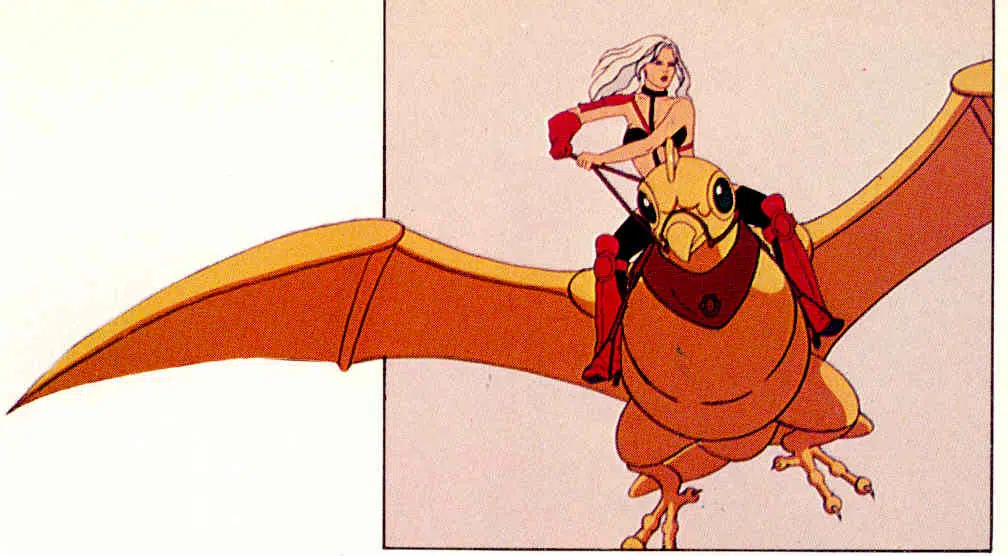

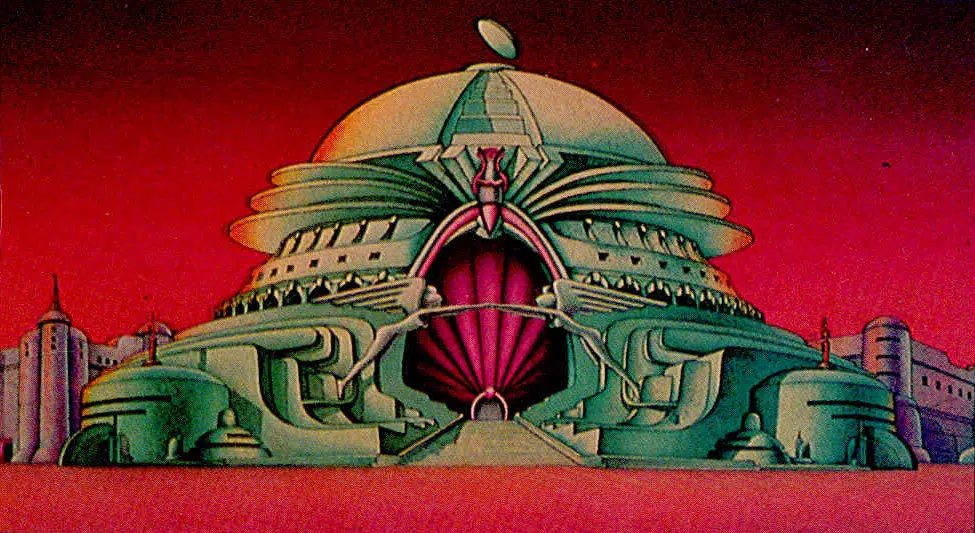

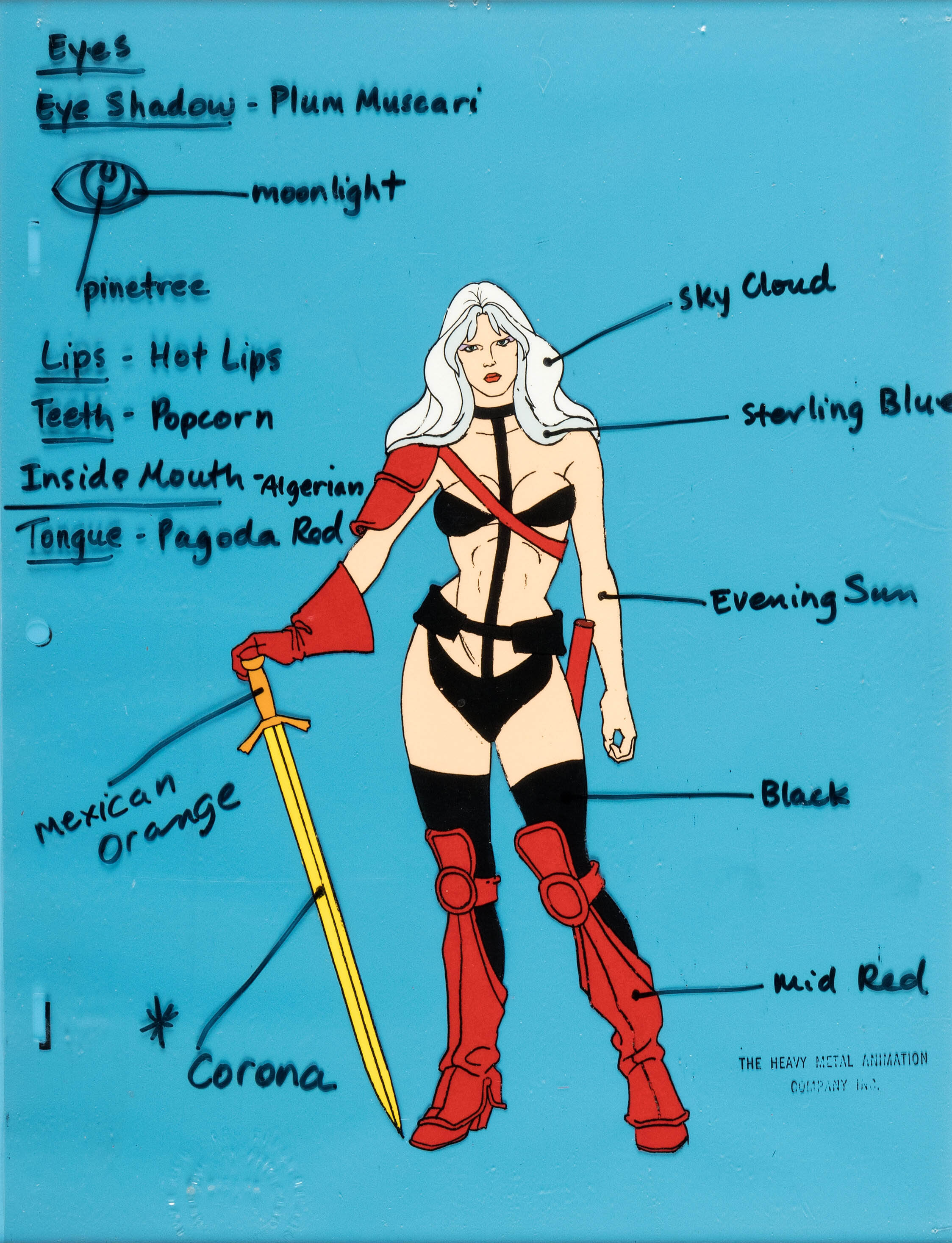

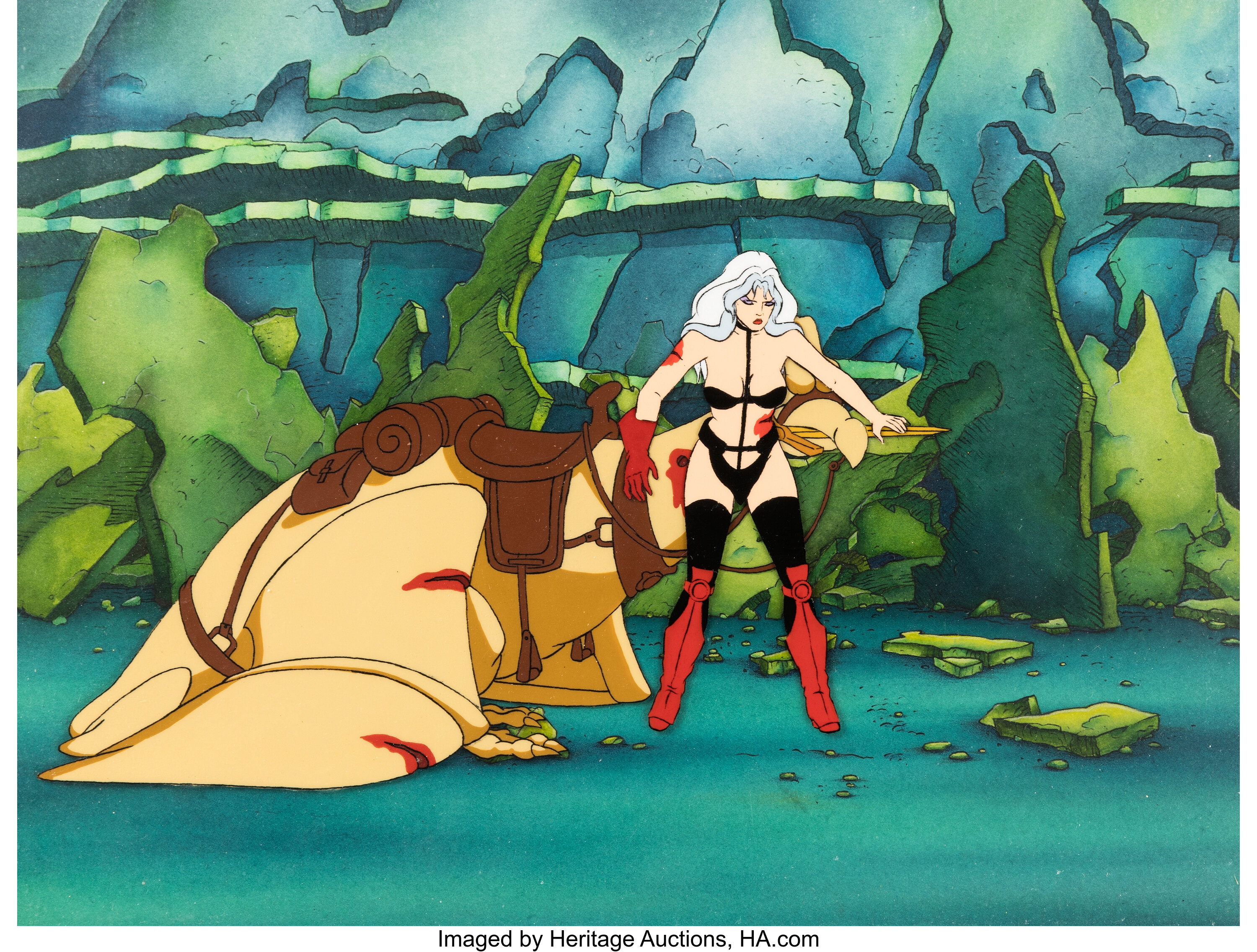

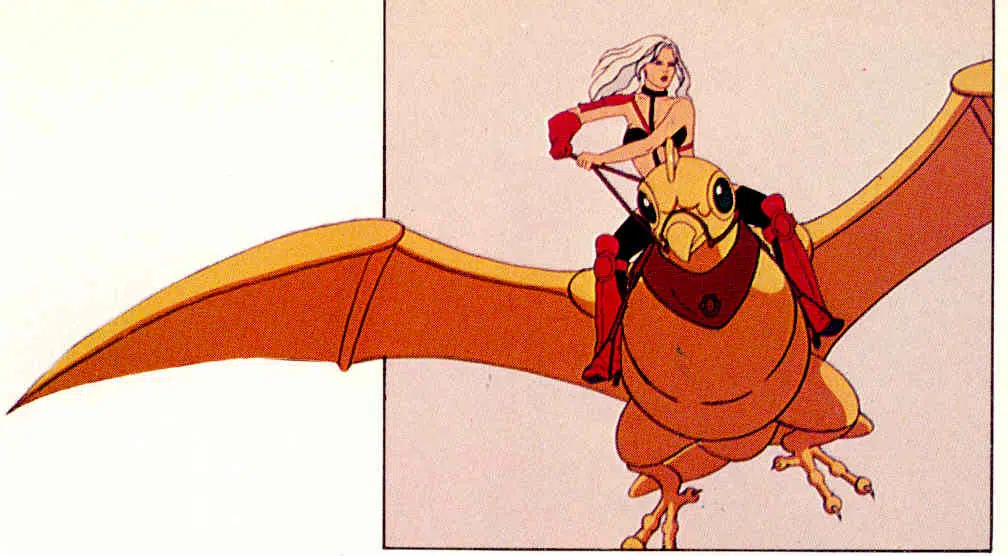

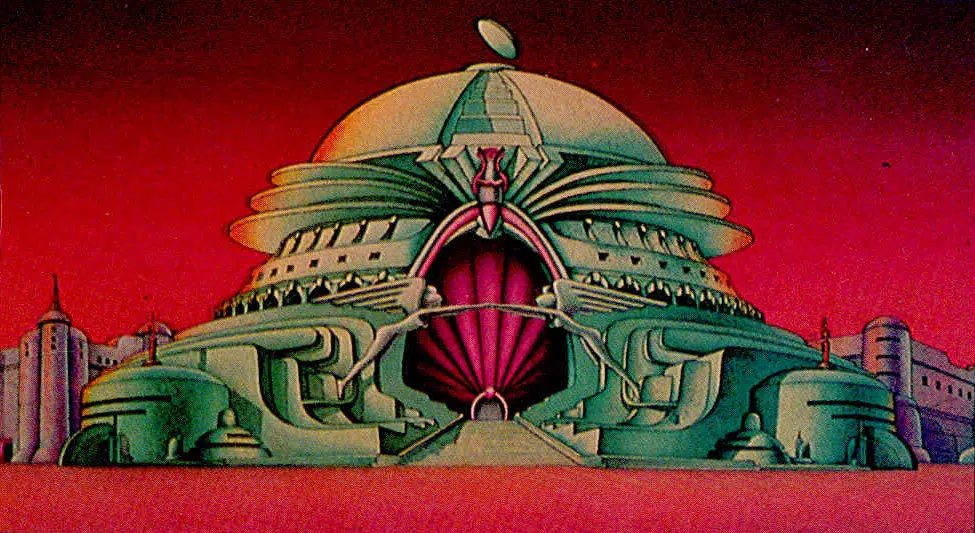

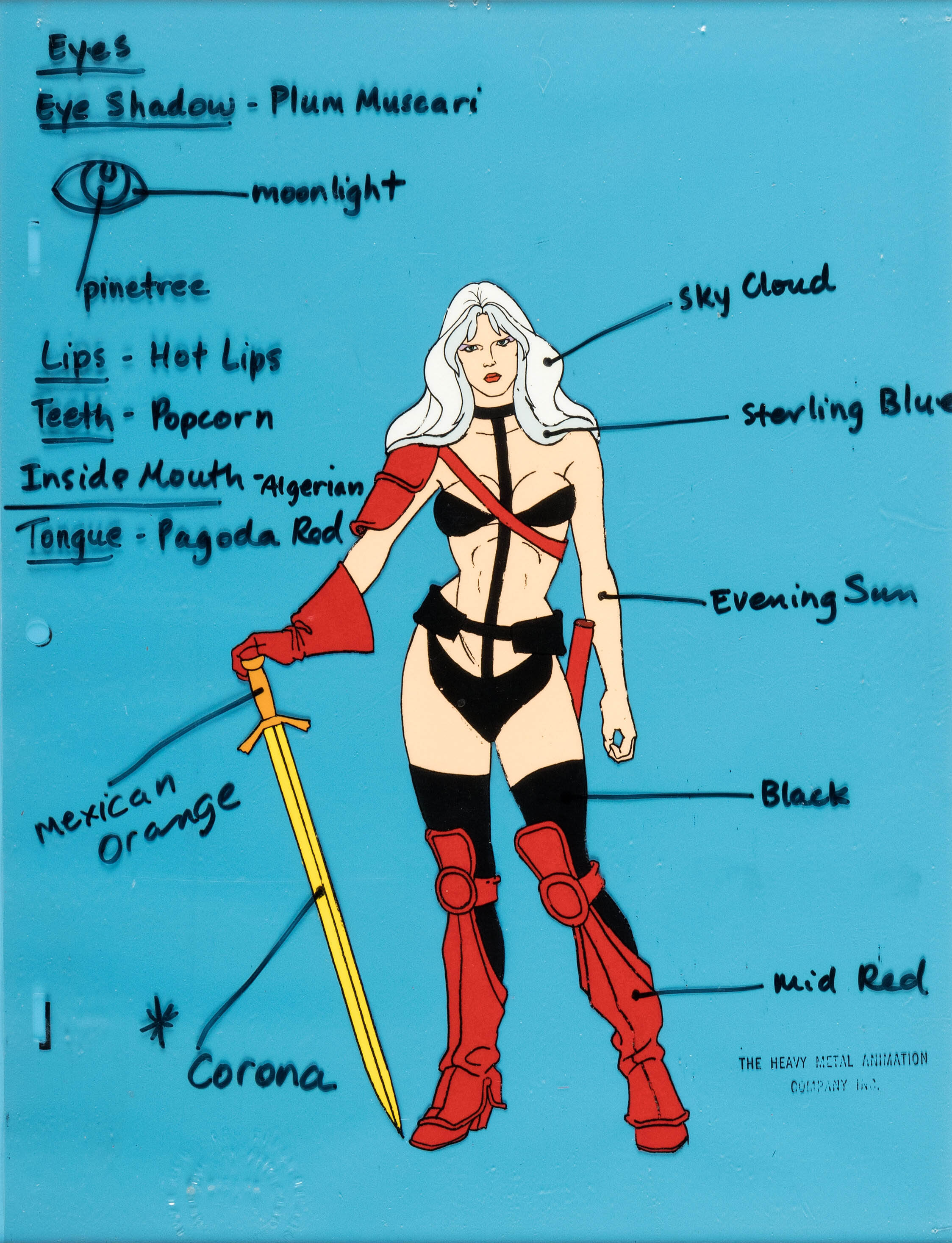

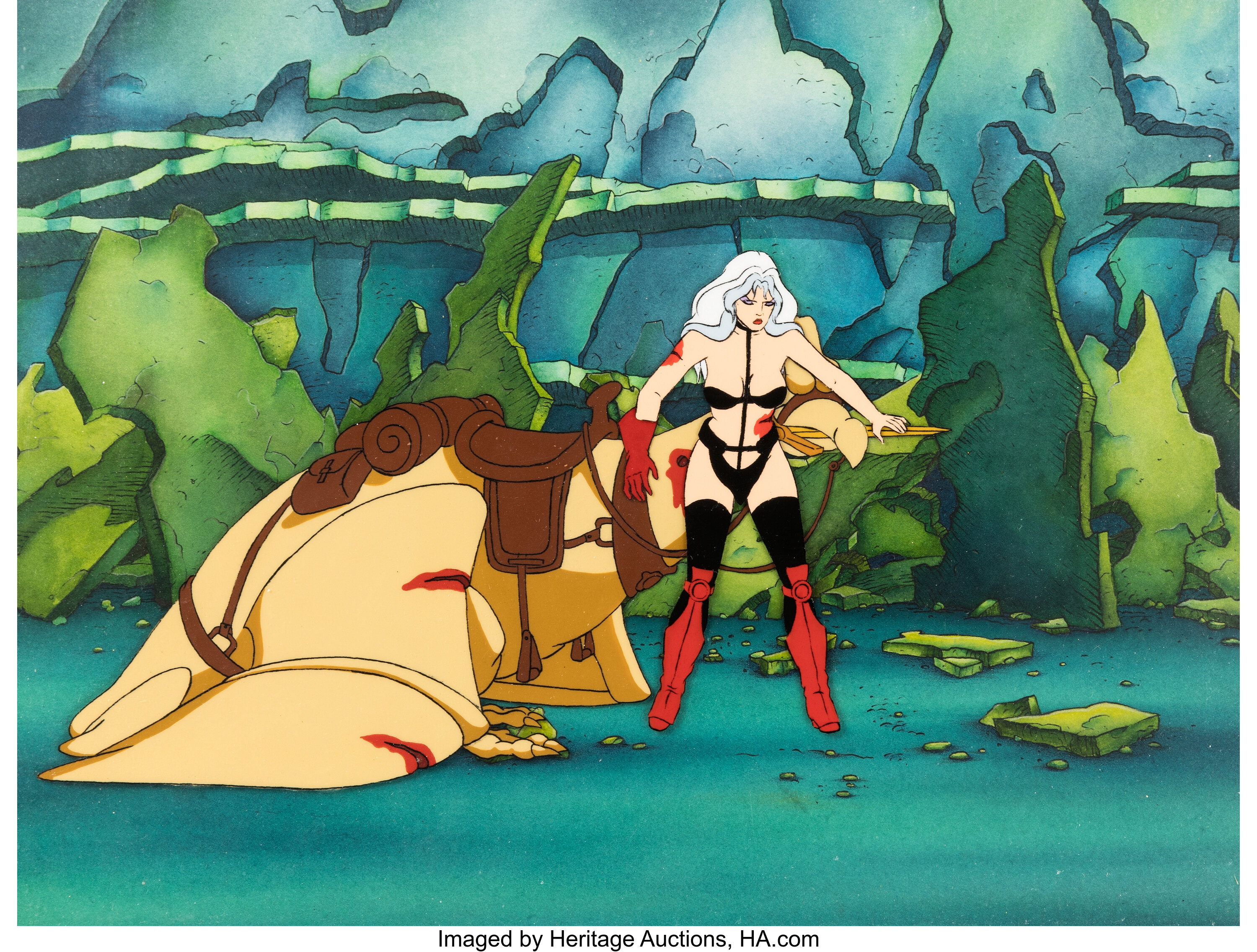

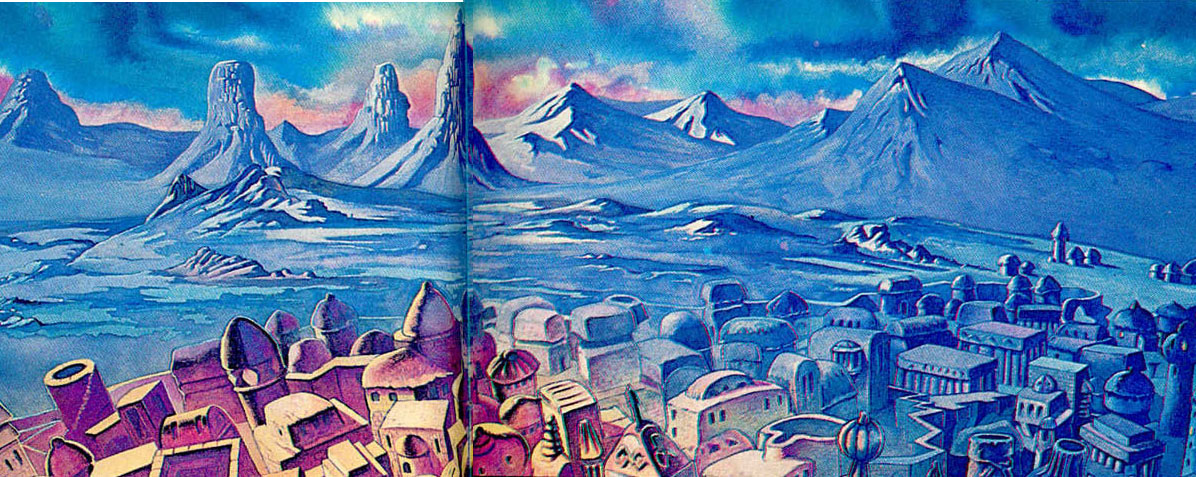

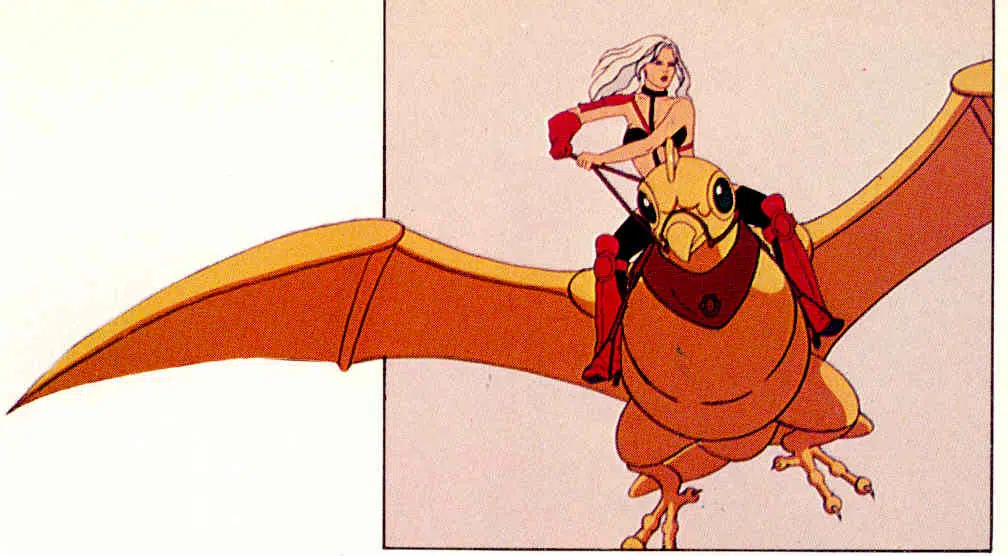

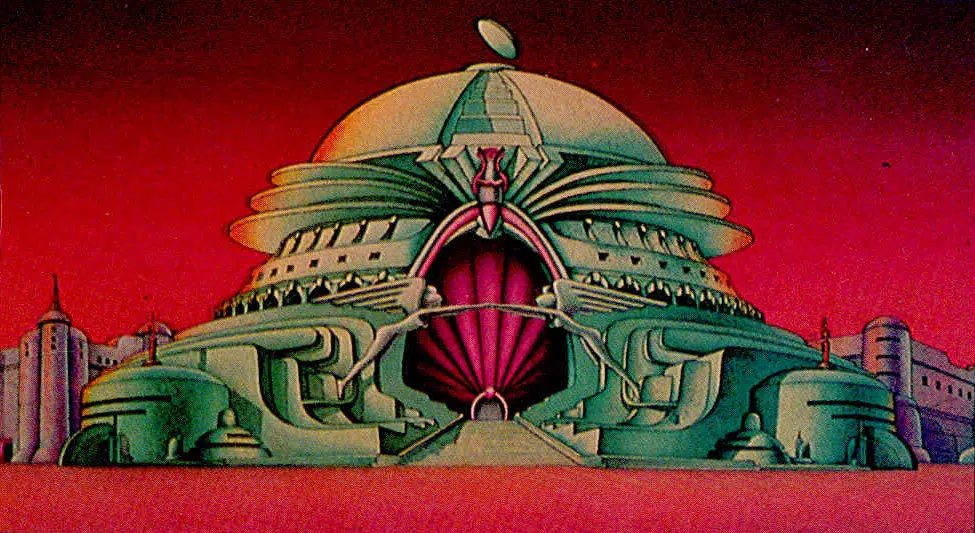

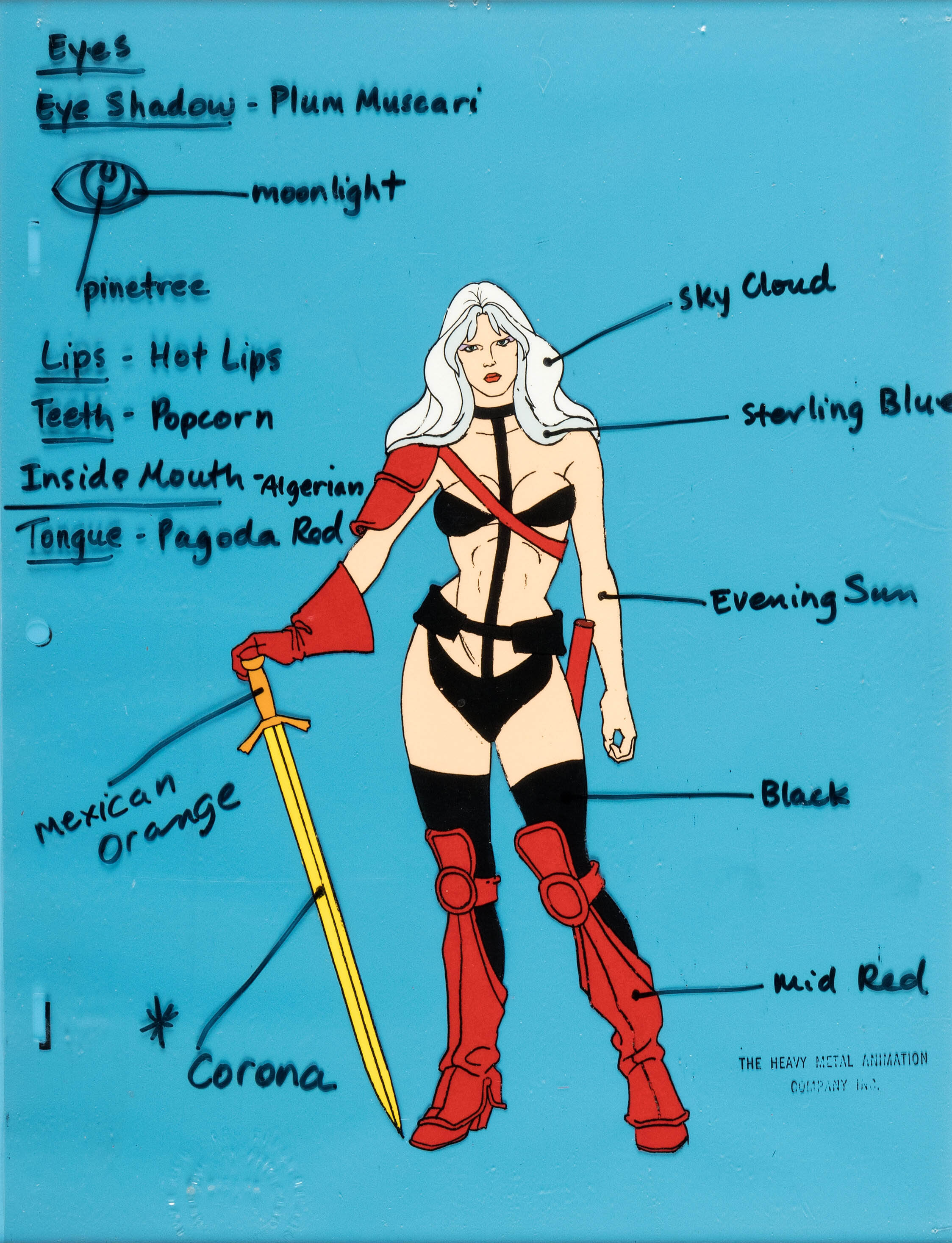

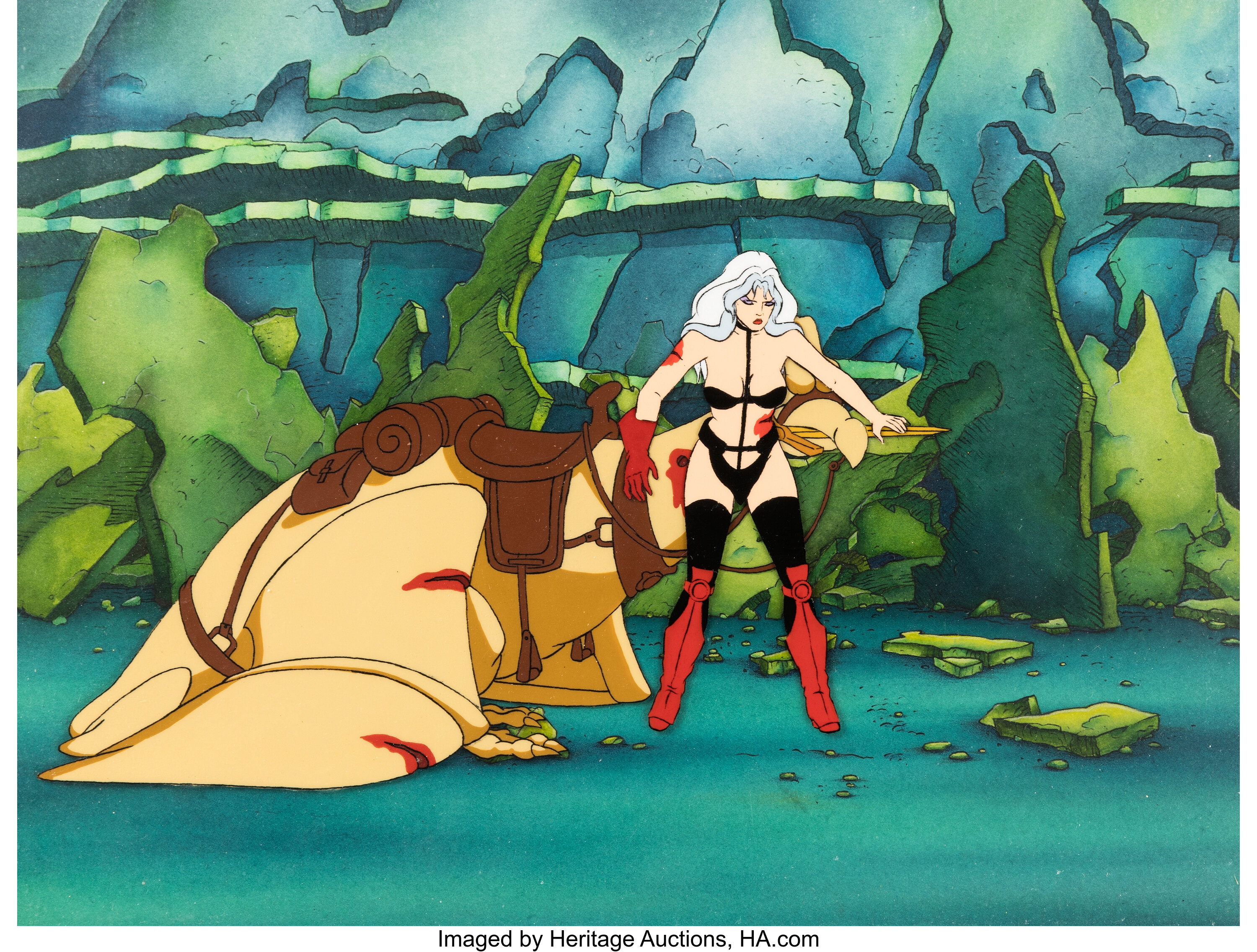

Finally the clincher, the piece de resistance, the grand finale: the twenty-seven-minute-long “Taarna,” a sequence which boasts perhaps a dozen lines of dialogue. Without giving away too much, let’s say that “Taarna” evokes the sense of wonder that every animation fan, sword-and-sorcery fan, feminist-SF fan, female-anatomy fan, mythology fan, weird-landscape-and-wild-beastie fan, or special-effects fan ever desires. As the sequence director, John Bruno, put it, “It fits the perfect formula for animation; it’s something impossible to do in live action. It’s all illusion, really, like doing magic.”

Never before has such a diverse set of stories, themes, visual techniques, and drawing styles been sewn together in one integrated whole. Other films, such as the classic Fantasia, were anthologies, but the drawing style was generally one studio’s uniform product. Here the techniques of many of the world’s finest animators have been applied to this one film to make it a visual and emotional roller coaster, ranging from scenes of pure fantasy to shocking horror to light-hearted whimsy. And since the film’s full animation vision hopes to achieve a smooth and lifelike feeling, even the most fantastic depictions appear realistic. Because the film is so intimately linked with the magazine’s sensibilities, its artists played a substantial part in creating the striking cinematic visuals. Thus artist-superstar Richard Corben produced model sheets for the animated version of his hero Den, and famed comics artist (National Lampoon, “Son-o’-God,” Green Lantern) Neal Adams envisioned characters for “So Beautiful and So Dangerous.” Angus McKie, Mike Ploog (doing art not only on “B-17” but also on “Taarna”), and Juan Gimenez (who did more than just concept drawings; he also planned model sheets for both “Harry Canyon” and “B-17”) have lent their immense talents to the project. Even acclaimed illustrator Charles White III and Alex Tavolarous (designer for Francis Ford Coppola) fashioned art-deco-style cities for “Taarna.”

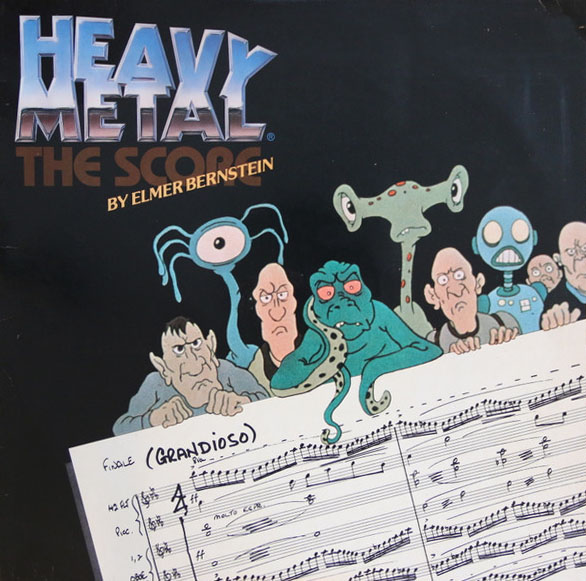

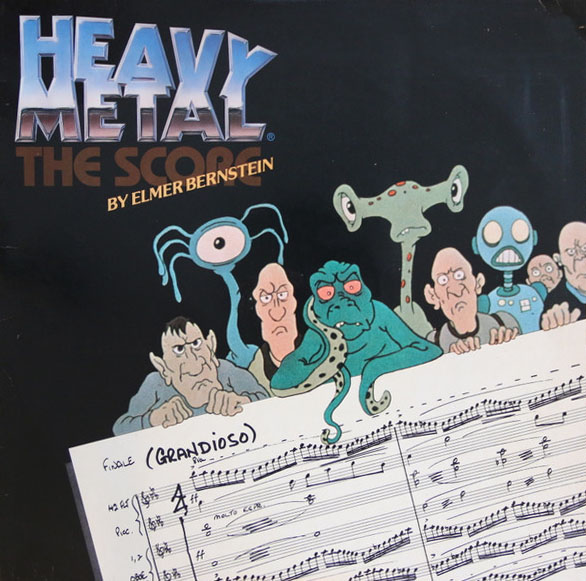

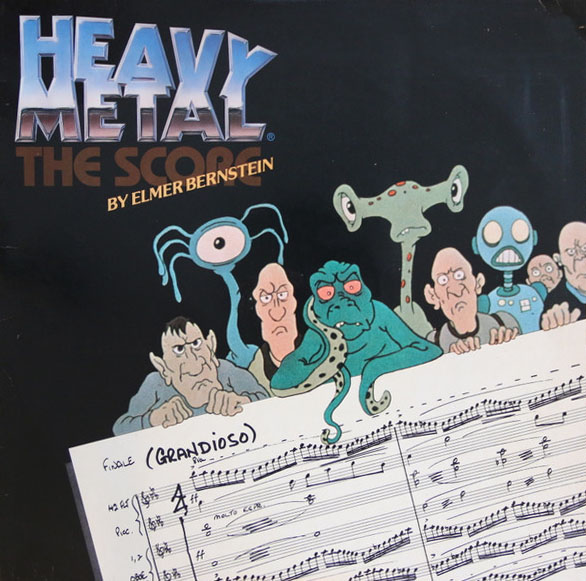

All this was done in order for the film to remain true to Heavy Metal, the mag. Through the magazine, adult subjects—particularly sexual ones—have been handled about as boldly as a comics-format magazine has ever handled them. And in the same adventurous spirit, the cinematic Heavy Metal also tackles realistic sex as it’s never been tackled before in an animated feature. To retain the realism of effect, the producers have stayed a mere hairbreadth away from an X rating. Nor has music been ignored: original pop music—written mostly for particular sequences—is set in an original score by Oscar-winning master composer Elmer Bernstein.

“For it to really capture the spirit of the magazine, it had to be an anthology,” says Mogel from behind his classically huge publisher’s desk. “What individual story could we have picked that represented the varied dynamics of the magazine and made one long, interesting story?”

It took Mogel from the summer of ’78 until the close of ’79 to develop the movie package. During that frenzied period, he had seen his project accepted, then rejected, by two major studios; he lost the story rights for three major illustrated works, had his animation budget doubled, and, during the whole process, earned his Ph.D. in determination.

In December ’79, Mogel decided to pursue the film’s financing in Canada. He called associate Simmons in Los Angeles and asked if he would consult his Animal House coproducer, Reitman, on the legal and governmental aspects of Canadian filmmaking. Reitman, a Canadian, got on the phone with Mogel and discussed the project as a whole.

One hour later, fascinated by the film’s possibilities, he told Mogel, “I can get the money and would like to produce it—let’s go.” Later, as he reflected on that decision, “it seemed like a great idea. I’d never seen an animated film since early childhood that excited me, so I thought it would be a challenge to make one.” The Toronto-born filmmaker adds, “Anyhow, I’ve seen most of the science-fiction and fantasy films ever made. I’m a big buff, so I really wanted to do an adult fantasy.”

Evidently, Columbia Pictures execs agreed with the wisdom of Reitman’s decision. Encouraged by his work for them on Stripes, they decided in late 1980 to distribute Heavy Metal, the movie.

But making the picture sounded simpler than reality has proven it to be, for even with its by-then tripled budget, no one fully comprehended what a massive undertaking was about to get underway. Nobody really could have, for they were attempting to do something not done before, bringing together all these diverse talents under one banner.

But Reitman hasn’t blanched at challenges. When he finished college in Toronto, Reitman formed a college-film distributing company, which gave him his first taste of film business. Then, at 25, he jumped into directing his first feature, a tongue-in-cheek horror number, Cannibal Girls—no great shakes as art but a drive-in money-maker. Finding out that his forte was making films, Reitman shifted to producing and hit big from the start, producing nouveau-horror-great director David Cronenberg’s first feature, They Came from Within—a controversial money-maker, and then Rabid. Shortly afterwards came National Lampoon’s Animal House. His fortunes further increased when he produced Meatballs, with Bill Murray, who now stars in Reitman’s comedy Stripes.

“I knew I had to tell a good story; that’s a basic of good moviemaking,” Reitman says assuredly. And with his own longtime love of comic books and the original Mad comic, he’s well suited to producing HM. “I knew it wouldn’t work as a regular movie,” the 35-year-old Canadian says. But he also knew it wasn’t that simple. “Though the artwork makes the magazine, you get bored with animation, the wonder of the designs, after ten minutes. So I figured, if we put together segments of shifting designs and story approaches, yet make them somehow connected, we could have the best of all worlds.”

So, when Reitman and fellow-Canadian scriptwriters Dan Goldberg and Len Blum jumped into mega-hour writing sessions late in February 1980, they pounced on making the film as broad as possible. To do so, this trio employed the same extrapolative techniques that make great science fiction work. “At each stage of the script,” explains Blum, “we had detailed understandings about each character and situation, which were not fleshed out in the script.” They remained true to the magazine’s values and even used a bit of method-acting thinking. There is an exercise which requires knowing a character’s whole life in order to play an hour of it; their knowledge of each character had to be more than what ends up on the screen.

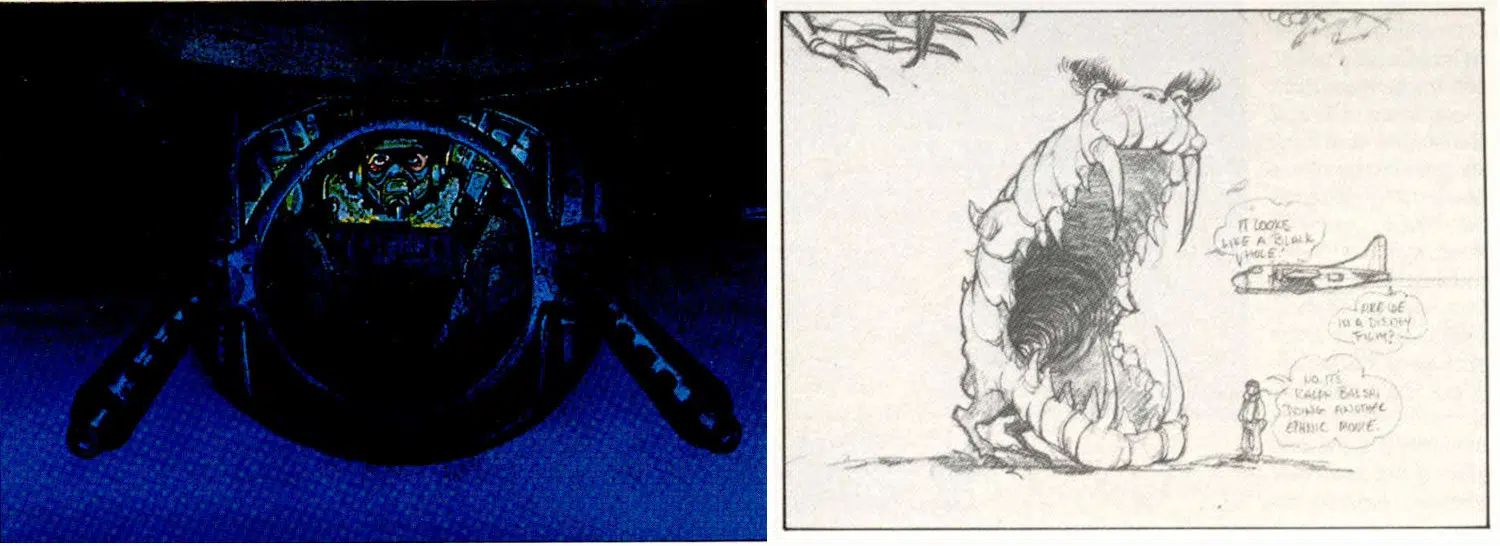

“For example, although you never know it on the screen,” explains Blum, “we knew that Zeke and Edsel, the space jockeys from ‘So Beautiful…,’ rocket around the galaxy collecting defective robots from various solar systems; they’re like outer-space Xerox repairmen.” These two writers also intended “Grimaldi” to have a strong mystical dose; made sure “Den” was a resolution of the teenage sexual fantasy; and made “B-17” as timeless a tale as possible.

To further insure Heavy Metal‘s visual success, former National Lampoon art director Michael Gross came to the project early on to maintain visual integrity. He became an associate producer, aiming to maintain quality all the way down the line. Gross, as an award-winning art director, conceived and edited the Lampoon‘s innovative comics pages and designed The Book of Alien.

Since the film was being financed in Canada—watchdogged by associate producer/financial manager Peter Lebensold—the HM animation headquarters was in Montreal, Canada, as well. Fortunately, this city is home to the acclaimed animation director Gerry Potterton. Executive producer Mogel had known of Potterton long before the Canadian financing, but once it became apparent that Canada was the place, Potterton fit right in like a puzzle piece.

Perfect, too, to have ex-Britisher Potterton at the helm, for this easygoing fifty-year-old director has done not only classic animation, like the “Raggedy Ann and Andy” feature, but live action as well. Potterton’s professional associations spanned the globe, so he was able to assemble what became the largest single animation operation in the Western world (400-plus personnel). And each of the many people involved has worked on at least one major animated project completed in the last 20 years.

Here in the Montreal nerve center on the third floor of the former Concordia University (incidentally, an art college) classrooms, Potterton does what no live-action director and few animation directors have ever done—that is, directs eight sequence directors, directing their individual segments. And he handles nearly sixty-five animators, each of whom is an artist who becomes an actor as he illustrates each character he’s supposed to portray. When a live-action director asks an actress to cross a set, she automatically sets body to motion; but an animator must consider not only the fact of that action but also its consequences: if the character is naked, then breasts bob; if clothed, fabric wrinkles. It’s a task of great detail and individual interpretation. The animation director is aware, too, of all that the animator can bring to or alter in a scene. All this Potterton must manage, as well as oversee the physical production of every stage from storyboard to final animation.

“My nature is to jump around, so it lends itself to making this film,” Potterton admits inside his office, jam-packed with Ploog sketches, where a production assistant is busily at work. He first got into animation at the Halas and Batchelor Studios, where 1954’s great breakthrough Animal Farm feature was made. “Unlike in live action, one thing’s for sure: you have to have a basic talent—drawing—to get into animation.” From there Potterton emigrated to Canada, eventually forming his own production company, which went on to do numerous TV specials, animated features, and live-action films, until its recent dissolution. While in a hiatus, he was offered the challenge of Heavy Metal. “You meet live-action people who say, ‘I wish I could do animation.’ It seems to me a hell of a lot easier to make the transition from animation to live action because you’re trained from the start to visualize in terms of already edited scenes. In animation, you can’t afford to shoot a scene several different ways; you must know what you want and do it right the first time!”

And here in Montreal they have guys giving him what he wants, guys like Portuguese-born Parisian Jose Abel, the animator of the young boy’s death scene in “Taarna.” When the kid goes to warn the council of a barbarian attack, he’s shot down, and Abel visualizes his body falling, the arrows piercing his throat, his eyes rolling back in his head, his tongue lolling out, and finally, the hands falling away in death. All in a few seconds. Some of the cel-colorists (ink-and-paint people) refused to work on the scene because it was so realistic. “You have to believe in what you are doing. You must somehow make it exist. You must forget it’s a drawing.”

They’ve done the job for Potterton in other places as well. Howard Chaykin holed up in LA’s Universal Sheraton for ten days drawing umpteen pictures a day. This illustrates perfectly the fanaticism surrounding the production. “I played the Philip Marlowe of animation! Since I was asked to create eclectic drawing for the ‘Taarna’ sequence, I had to avoid making them Conan clones or making Taarna another Barbarella. So I hid away and concentrated on Japanese design, which has that SF sort of stylization anyhow.”

In London, the grandiose sign announcing Halas and Batchelor greets the visitor to Europe’s premier animation studio and theater for work on “So Beautiful.” Inside, major domo John Halas speaks of life with the late great SF film director George Pal in their native Budapest. The 69-year-old Halas now dominates world animation unlike anyone else this side of departed demigod Walt Disney. “In various spheres of art come those who define it; I am one in animation.” Possessing a track record that includes the brilliant, subtly political Animal Farm (Britain’s first full-length animated film); the Oscar-nominated Automania 2000 and Dream Doll; and the electronic-music-inspired “Autobahn” short, Halas can speak with authority: “Only animation can provide the humor and personality needed to portray the charismatic robot in ‘So Beautiful.’ The Heavy Metal movie will be a milestone in animation. and I’m proud to assist in its architectural structuralization.”

London also houses the production team for “Den,” “Soft Landing,” and part of “Grimaldi.” Among the “Den” crew, led by sequence director Jack Stokes—he too is an alumnus of Yellow Submarine—are some of the finest European animators working in the field today. Many are both Halas and Potterton grads. Animation miniatures expert Teru (Jimmy) Murakami was once the animation director for Frank Zappa and the head of a company that produced Puff, the Magic Dragon. He also directed the live-action feature film Battle Beyond the Stars. Elemental in his work is the elaborate combination of model work, rotoscoping, special effects, and air-brushing, all intended to make “Soft Landing” an opening sequence of visual wonderment. “If you could just get rid of the attitude that animation has to be cute,” reflects Murakami, “that would be great progress. I think a film like this could do that. It’s all a matter of getting the public to see animation as something other than cartoons. I’ve always tried to do animation that was more than that.”

In Malibu, “B-17” sequence director Barrie Nelson adjusts to the chore of animating the rousing horror treatment after building a career on the very opposite—whimsical, light shorts. Simultaneously, in Montreal, directors Julian Scuchopa and Paul Sabella cap off a career started at Potterton Productions by animating “Captain Sternn.”

And throughout the world, special-effects experts with hefty experience on such weighty effects masterpieces as Superman, Star Wars, and Star Trek toil away on Heavy Metal. Because of work on the film, even Disney has been affected. When word went out that ace cameraman Max Morgan modified his multiplane camera to do special shots in “Taarna,” the Disney Studios brought their original machine out of twenty-year-old mothballs.

With all of this, there are funny anecdotes that buoy up morale for such a massive and frantic community of animators. A Christmas card was circulated depicting Taarna lasciviously on Santa’s knee; graffiti in the men’s room in HM HQ read, “For a good time, call Taarna,” and listed the office phone number; the Ottawa studio doing “Harry Canyon” has an off-color guide to ethnic types of New York City in the future. But possibly the funniest was the “Bald Vagina” incident. After Gross and gang in London had a good look at the sex scene in “Den” where Kath makes the most of her nudity, they all noticed the reproduction of Corben’s bald vaginas on the storyboards. A memo went to producer Reitman asking about alternatives, or, “Do we go with the slit and damn the torpedoes?” The lines such a production inspires!

Finally, to pull the film together, Reitman concentrated on music as the work neared completion. First, the task of scoring the film went to maestro Elmer Bernstein. Master manager Irving Azoff pledged to spend any amount of money needed to assemble the best possible bands and songs for the two discs.

A world-renowned film composer, the 59-year-old Bernstein has won accolades and Oscars for his 130 film scores. The diversity is remarkable—True Grit, To Kill a Mockingbird, and National Lampoon’s Animal House are but a few. Azoff—a former midwestern college-concert promoter—now handles the heaviest of platinum-earning rockers, such as Steely Dan, the Eagles, and Stevie Nicks: auspicious credits but worlds apart in the music business. Yet, Reitman has delegated to these two the task of realizing the musical ambience of Heavy Metal. “It’s a matter of the degree by which you integrate different musical elements,” says Bernstein from his home-studio in Santa Barbara, California. “Obviously you pick music that stimulates a reaction. Since the animation medium is not lifelike, your music must really fit—it has to be something full, huge, adventurous.”

For Azoff, the assignment to gather various musical submissions to play for Reitman fell to Bob DeStocki, a burly ex-Ohioan and former Elektra-Asylum staffer. DeStocki must first interest world-class chart-topping bands, then convince them to send in original selections for consideration, and finally hustle them to finish acceptable demos for actual recording within the film’s deadlines. “Some of these guys have never done anything on deadline in their lives,” chuckles DeStocki, but it’s up to him to make them understand how unusual an opportunity this is—it’s the first time an animated film has tried for a totally original score. Of course, whom to ask troubled him because of his own initial unfamiliarity with the magazine. “It was soon clear that this movie is much more than one musical style.” Once DeStocki began looking, first in his own backyard and expanding outwards from there, he found bands agog with enthusiasm.

“When we got the script, it was like a dream come true,” says Blue Oyster Cult drummer Albert Bouchard. “And when I had read about the film just a few Heavy Metals before, I had hoped the music would be good. We always wanted to do a cinematic version of songs; we felt they demanded it. Now at least we get a chance to do something like that in reverse.” For the Cult, whose songs such as their hit “Don’t Fear the Reaper” have always had a macabre edge, doing the movie was more than a coincidence: it served to inspire the musical ideas for their upcoming album. “We didn’t really have any idea of what we were going to do and figured we’d wait till we got into the studio. Then, once we looked at the script, the music flowed, and we did five songs in a few days.”

For Black Sabbath lead singer Ronnie Dio, it was a similar opportunity to try something different. “We’ve always been interested in taking our audience beyond the realm of everyday life, so when we saw the script we said, ‘Perfect.’ Animation takes you out of the realm of the real, so we tried for some-thing that would take us out of the realm of what we ordinarily do.” The Cult and the Sabs treated their heavy-metal bombast to strong doses of electronics and extended instrumentals for the perfect effect.

But it was Devo’s Jerry Casale who summed up what the music in this film is all about. “Music in a soundtrack like this has to give an added dimension to it all. Since things are totally defined, the music should inspire the imagination.” Devo certainly tried for that, with two cuts that went beyond all expectations, “Be Cool” and “Working in Coal Mine” (the latter, says Gross, is the unofficial animator’s theme song). “So far other animated films have been limited to cartoonish images or the Bakshi style like in American Pop,” sums up Casale, explaining his own fascination with the HM idea. “An animated version of the magazine, which is so fantasy oriented, comes at an opportune time, especially in the wake of the sword-and-sorcery revival and the new Romantics things. There is a move toward re-evaluating our culture to make it seem more like a jungle, in order to make the familiar exciting again.”

Heavy Metal: The Making of the Movie (from August 1981)

Heavy Metal: The Making of the Movie (from August 1981)

Heavy Metal, the movie, had its premiere 40 years ago today—July 29, 1981—and opened nationwide a week later. To celebrate the anniversary we’ve got a treat for fans: The “Making of” article that ran in the August 1981 issue of Heavy Metal. This will bring back memories and will likely induce a strong urge to watch the film. Enjoy.

NOTE: Additional images have been added to this article

by Brad Balfour

Take 70 animators from 14 different countries, guys who have worked on everything from Sylvester the Cat to J.R.R. Tolkien’s hobbits. Put them in ten different studios stretching from the West Coast to London, with the nerve center in Montreal, somewhere in between. Give them characters and situations devised by writers who have previously written the highest-grossing Canadian film ever, and a director who has worked with such notables as Buster Keaton and Harold Pinter. Add to this already inspired mix astounding graphics and design sketches by some of the world’s hottest fantasy-art geniuses, artists loved and respected worldwide. Don’t forget a producer who at 27 started raking in bundles in Canada because he produced a young horror-filmmaker’s surprisingly good and profitable ideas, and later coproduced the 11th-highest-grossing film ever. Finally, base this on a magazine of illustrated science-fiction and fantasy stories, material of international renown, whose contents are reviewed in major French newspapers on a par with the way high art is covered, and whose illustrators include artists from Japan to the Netherlands. Take it all to Columbia Pictures, who distributed one of the finest science-fiction films in years, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, where the executives on the Burbank lot say, “This whole package is so fantastic, let’s make it our big film for the summer’s end.”

I’m talkin’ about Heavy Metal—the movie; talkin’ about Heavy Metal—the magazine.

And it was like something from a dream—the spirit of fate or the force of coincidence at work—that while publisher Len Mogel was in Paris negotiating rights with a small French publisher to produce a French version of National Lampoon, his wife, Ann, picked up a copy of their new magazine, Metal Hurlant. Both the Mogels were enthralled with its contents—illustrated science fiction and fantasy for adults laced with a strong dose of the absurd, drawn like fine art.

Mogel was determined to publish an English-language magazine presenting this new artistic concept, and he quickly won over his colleagues. Heavy Metal began publication in April 1977.

Mogel and crew found that after a mere five issues premiered, Heavy Metal quickly garnered over 100,000 readers. It was then that they knew they had something remarkable in hand. A year later—with the phenomenal success of Matty Simmons and Ivan Reitman’s National Lampoon’s Animal House as inspiration—the dream of a Heavy Metal movie took form.

The connection between comics and cinema is a natural one. Both deal in illusion, in actualized fantasy. Continuity of image and simple storytelling separate the successful story, told either in panel-art form or on celluloid, from the mediocre. The telling of a story through connected image and dialogue has been attempted since the first caveman painted sequential images on stone. Film is merely the execution of that idea in a modern way. As for the conjunction of comics and animation—well, what else could there be? Drawn images on a screen—drawn images on a page.

The Heavy Metal movie cried out to be animated. What else could capture the absurdist/dadaist/surrealistic urgings of the mag’s original art? Not live action, for then the extraordinary is rendered as the everyday. To keep the material in the realm of the imagined—in the region of mind that can plan out an entire world in sequential drawings—was the only appropriate choice.

Just imagine: a person draws, from nothing but disparate images in the head, a cohesive whole composed of hundreds of little scenes (the longest sequence in Heavy Metal consists of 330 scenes) made up of close to 130,000 individual drawings. Finally it’s the experience of an audience exchanging belief in the regular world of the photographic for the totally unreal world of the drawn, which then takes on a life of its own. And Heavy Metal, the movie, goes even beyond that.

It goes something like this, as one scriptwriter, Len Blum, puts it, “from one universe into another.” It opens with the “Soft Landing” sequence, based on art by Thomas Warkentin, from an idea of Alien scriptwriter Dan O’Bannon [originally published in the Sept. ’79 Heavy Metal]. After this 2001: A Space Odyssey–like prologue, it shifts rather handily into the quasi-mystical “Grimaldi” story—the key linking device be-tween sequences. From this intro we jump into “Den,” the adaptation of Richard Corben‘s brilliantly drawn quintessential hero fiction, which ran during HM‘s first year. It presented the greatest challenge to bring to the screen. Corben’s spectacular color values were carefully maintained in the backgrounds, with bizarre expanses glowing in rich, fluorescent hues. The tale of young Dan’s transformation into the hero Den, who’s caught in the power struggle between the sorcerer Ard and the queen-priestess, is told with two near-explicit sex scenes amidst lots of solid, hand-to-hand combat.

From these staggering visuals, the film carries us into the galactic court where Captain Sternn is on trial. From comic-artist great Berni Wrightson‘s original story [published in the June ’80 HM], Sternn is the ultimate parody of every space-opera villain-hero. Says artist Wrightson, “I’ve always had trouble writing something serious. So when Captain Sternn grew out of Star Wars—I was never an SF fan until I saw it—as a funny adventure, it degenerated into a broad farce. I was also inspired by Warner Bros. cartoons; hence I created his foil character, Hanover Fiste.” As the story leaves the conclusion of the trial, it moves into the “Neverwhere” world—master animator Cornelius Cole’s personal vision of the history of evil as a basic force in history. Cole’s visionary graphics (intricate ball-point renderings of lyric pastels) get most viewers to say, “Holy shit, this stuff is really coming to life!” Says Cole, “You reach a point in animation where you must have the opportunity not to cut corners.”

On to “B-17,” the first true horror story to be animated, with all the savagery that makes great shockers. Will Eisner–trained film artist Mike Ploog did most of the conceptualizations. His background as a former Marvel Comics “Conan” and “Frankenstein” artist lends greater power to this 1950s E.C. Comics–style terror tale. A favorite of producer Reitman’s since he was an E.C. collector as a kid, the story (based on an original idea of O’Bannon’s) was given a twist of authenticity. They visited an aviation museum, and one of the last few flyable B-17s was flown in order to record actual sound effects of the plane. Coincidentally, the HM animation team includes three WWII bomber crew-men, several licensed pilots, an ex-RAF inductee, and a director who collects aviation memorabilia.

With the following sequence, “So Beautiful and So Dangerous,” came the original artist, Angus McKie, who illustrated the serial in HM, which later became a book. He directly contributed 70 key background paintings of the most incredible animated sequences ever done. The contrast between McKie’s high-tech environments and the three space jockeys (well, two, and one robot) are inspired by Cheech and Chong. There are lots of outer-space drug references and some interstellar sex.

Gimenez’s “Harry Canyon” is an original depiction of a world half-familiar—New York City—in an unfamiliar time, 2031. The misadventures of a cynical cab driver caught in the middle of a battle for valuable stolen goods comes right out of a thirties detective story. “We sort of thought of it as an animated variation of Dashiell Hammett’s Maltese Falcon, starring Humphrey Bogart,” says the other scriptwriter, Dan Goldberg. This New York of the future is everything the current NYC is, only more: there’s Times Square with cheap, rip-off churches; a cop station that charges to aid the troubled; a Statue of Liberty no longer in the bay but surrounded by skyscrapers; and a Brooklyn Bridge graced with the sign “Use at your own risk.” Ironically, all of this was initially envisioned by the exceptional South American illustrator Juan Gimenez, who had never visited New York when he did the subtle drawings. He imagined a New York City unprejudiced by its reality—a reality that he discovered only weeks after his four-month drawing stint in Canada. When brought to New York to visit the HM office he saw the Pan Am building and exclaimed, “It really does exist as I saw it!”

Finally the clincher, the piece de resistance, the grand finale: the twenty-seven-minute-long “Taarna,” a sequence which boasts perhaps a dozen lines of dialogue. Without giving away too much, let’s say that “Taarna” evokes the sense of wonder that every animation fan, sword-and-sorcery fan, feminist-SF fan, female-anatomy fan, mythology fan, weird-landscape-and-wild-beastie fan, or special-effects fan ever desires. As the sequence director, John Bruno, put it, “It fits the perfect formula for animation; it’s something impossible to do in live action. It’s all illusion, really, like doing magic.”

Never before has such a diverse set of stories, themes, visual techniques, and drawing styles been sewn together in one integrated whole. Other films, such as the classic Fantasia, were anthologies, but the drawing style was generally one studio’s uniform product. Here the techniques of many of the world’s finest animators have been applied to this one film to make it a visual and emotional roller coaster, ranging from scenes of pure fantasy to shocking horror to light-hearted whimsy. And since the film’s full animation vision hopes to achieve a smooth and lifelike feeling, even the most fantastic depictions appear realistic. Because the film is so intimately linked with the magazine’s sensibilities, its artists played a substantial part in creating the striking cinematic visuals. Thus artist-superstar Richard Corben produced model sheets for the animated version of his hero Den, and famed comics artist (National Lampoon, “Son-o’-God,” Green Lantern) Neal Adams envisioned characters for “So Beautiful and So Dangerous.” Angus McKie, Mike Ploog (doing art not only on “B-17” but also on “Taarna”), and Juan Gimenez (who did more than just concept drawings; he also planned model sheets for both “Harry Canyon” and “B-17”) have lent their immense talents to the project. Even acclaimed illustrator Charles White III and Alex Tavolarous (designer for Francis Ford Coppola) fashioned art-deco-style cities for “Taarna.”

All this was done in order for the film to remain true to Heavy Metal, the mag. Through the magazine, adult subjects—particularly sexual ones—have been handled about as boldly as a comics-format magazine has ever handled them. And in the same adventurous spirit, the cinematic Heavy Metal also tackles realistic sex as it’s never been tackled before in an animated feature. To retain the realism of effect, the producers have stayed a mere hairbreadth away from an X rating. Nor has music been ignored: original pop music—written mostly for particular sequences—is set in an original score by Oscar-winning master composer Elmer Bernstein.

“For it to really capture the spirit of the magazine, it had to be an anthology,” says Mogel from behind his classically huge publisher’s desk. “What individual story could we have picked that represented the varied dynamics of the magazine and made one long, interesting story?”

It took Mogel from the summer of ’78 until the close of ’79 to develop the movie package. During that frenzied period, he had seen his project accepted, then rejected, by two major studios; he lost the story rights for three major illustrated works, had his animation budget doubled, and, during the whole process, earned his Ph.D. in determination.

In December ’79, Mogel decided to pursue the film’s financing in Canada. He called associate Simmons in Los Angeles and asked if he would consult his Animal House coproducer, Reitman, on the legal and governmental aspects of Canadian filmmaking. Reitman, a Canadian, got on the phone with Mogel and discussed the project as a whole.

One hour later, fascinated by the film’s possibilities, he told Mogel, “I can get the money and would like to produce it—let’s go.” Later, as he reflected on that decision, “it seemed like a great idea. I’d never seen an animated film since early childhood that excited me, so I thought it would be a challenge to make one.” The Toronto-born filmmaker adds, “Anyhow, I’ve seen most of the science-fiction and fantasy films ever made. I’m a big buff, so I really wanted to do an adult fantasy.”

Evidently, Columbia Pictures execs agreed with the wisdom of Reitman’s decision. Encouraged by his work for them on Stripes, they decided in late 1980 to distribute Heavy Metal, the movie.

But making the picture sounded simpler than reality has proven it to be, for even with its by-then tripled budget, no one fully comprehended what a massive undertaking was about to get underway. Nobody really could have, for they were attempting to do something not done before, bringing together all these diverse talents under one banner.

But Reitman hasn’t blanched at challenges. When he finished college in Toronto, Reitman formed a college-film distributing company, which gave him his first taste of film business. Then, at 25, he jumped into directing his first feature, a tongue-in-cheek horror number, Cannibal Girls—no great shakes as art but a drive-in money-maker. Finding out that his forte was making films, Reitman shifted to producing and hit big from the start, producing nouveau-horror-great director David Cronenberg’s first feature, They Came from Within—a controversial money-maker, and then Rabid. Shortly afterwards came National Lampoon’s Animal House. His fortunes further increased when he produced Meatballs, with Bill Murray, who now stars in Reitman’s comedy Stripes.

“I knew I had to tell a good story; that’s a basic of good moviemaking,” Reitman says assuredly. And with his own longtime love of comic books and the original Mad comic, he’s well suited to producing HM. “I knew it wouldn’t work as a regular movie,” the 35-year-old Canadian says. But he also knew it wasn’t that simple. “Though the artwork makes the magazine, you get bored with animation, the wonder of the designs, after ten minutes. So I figured, if we put together segments of shifting designs and story approaches, yet make them somehow connected, we could have the best of all worlds.”

So, when Reitman and fellow-Canadian scriptwriters Dan Goldberg and Len Blum jumped into mega-hour writing sessions late in February 1980, they pounced on making the film as broad as possible. To do so, this trio employed the same extrapolative techniques that make great science fiction work. “At each stage of the script,” explains Blum, “we had detailed understandings about each character and situation, which were not fleshed out in the script.” They remained true to the magazine’s values and even used a bit of method-acting thinking. There is an exercise which requires knowing a character’s whole life in order to play an hour of it; their knowledge of each character had to be more than what ends up on the screen.

“For example, although you never know it on the screen,” explains Blum, “we knew that Zeke and Edsel, the space jockeys from ‘So Beautiful…,’ rocket around the galaxy collecting defective robots from various solar systems; they’re like outer-space Xerox repairmen.” These two writers also intended “Grimaldi” to have a strong mystical dose; made sure “Den” was a resolution of the teenage sexual fantasy; and made “B-17” as timeless a tale as possible.

To further insure Heavy Metal‘s visual success, former National Lampoon art director Michael Gross came to the project early on to maintain visual integrity. He became an associate producer, aiming to maintain quality all the way down the line. Gross, as an award-winning art director, conceived and edited the Lampoon‘s innovative comics pages and designed The Book of Alien.

Since the film was being financed in Canada—watchdogged by associate producer/financial manager Peter Lebensold—the HM animation headquarters was in Montreal, Canada, as well. Fortunately, this city is home to the acclaimed animation director Gerry Potterton. Executive producer Mogel had known of Potterton long before the Canadian financing, but once it became apparent that Canada was the place, Potterton fit right in like a puzzle piece.

Perfect, too, to have ex-Britisher Potterton at the helm, for this easygoing fifty-year-old director has done not only classic animation, like the “Raggedy Ann and Andy” feature, but live action as well. Potterton’s professional associations spanned the globe, so he was able to assemble what became the largest single animation operation in the Western world (400-plus personnel). And each of the many people involved has worked on at least one major animated project completed in the last 20 years.

Here in the Montreal nerve center on the third floor of the former Concordia University (incidentally, an art college) classrooms, Potterton does what no live-action director and few animation directors have ever done—that is, directs eight sequence directors, directing their individual segments. And he handles nearly sixty-five animators, each of whom is an artist who becomes an actor as he illustrates each character he’s supposed to portray. When a live-action director asks an actress to cross a set, she automatically sets body to motion; but an animator must consider not only the fact of that action but also its consequences: if the character is naked, then breasts bob; if clothed, fabric wrinkles. It’s a task of great detail and individual interpretation. The animation director is aware, too, of all that the animator can bring to or alter in a scene. All this Potterton must manage, as well as oversee the physical production of every stage from storyboard to final animation.

“My nature is to jump around, so it lends itself to making this film,” Potterton admits inside his office, jam-packed with Ploog sketches, where a production assistant is busily at work. He first got into animation at the Halas and Batchelor Studios, where 1954’s great breakthrough Animal Farm feature was made. “Unlike in live action, one thing’s for sure: you have to have a basic talent—drawing—to get into animation.” From there Potterton emigrated to Canada, eventually forming his own production company, which went on to do numerous TV specials, animated features, and live-action films, until its recent dissolution. While in a hiatus, he was offered the challenge of Heavy Metal. “You meet live-action people who say, ‘I wish I could do animation.’ It seems to me a hell of a lot easier to make the transition from animation to live action because you’re trained from the start to visualize in terms of already edited scenes. In animation, you can’t afford to shoot a scene several different ways; you must know what you want and do it right the first time!”

And here in Montreal they have guys giving him what he wants, guys like Portuguese-born Parisian Jose Abel, the animator of the young boy’s death scene in “Taarna.” When the kid goes to warn the council of a barbarian attack, he’s shot down, and Abel visualizes his body falling, the arrows piercing his throat, his eyes rolling back in his head, his tongue lolling out, and finally, the hands falling away in death. All in a few seconds. Some of the cel-colorists (ink-and-paint people) refused to work on the scene because it was so realistic. “You have to believe in what you are doing. You must somehow make it exist. You must forget it’s a drawing.”

They’ve done the job for Potterton in other places as well. Howard Chaykin holed up in LA’s Universal Sheraton for ten days drawing umpteen pictures a day. This illustrates perfectly the fanaticism surrounding the production. “I played the Philip Marlowe of animation! Since I was asked to create eclectic drawing for the ‘Taarna’ sequence, I had to avoid making them Conan clones or making Taarna another Barbarella. So I hid away and concentrated on Japanese design, which has that SF sort of stylization anyhow.”

In London, the grandiose sign announcing Halas and Batchelor greets the visitor to Europe’s premier animation studio and theater for work on “So Beautiful.” Inside, major domo John Halas speaks of life with the late great SF film director George Pal in their native Budapest. The 69-year-old Halas now dominates world animation unlike anyone else this side of departed demigod Walt Disney. “In various spheres of art come those who define it; I am one in animation.” Possessing a track record that includes the brilliant, subtly political Animal Farm (Britain’s first full-length animated film); the Oscar-nominated Automania 2000 and Dream Doll; and the electronic-music-inspired “Autobahn” short, Halas can speak with authority: “Only animation can provide the humor and personality needed to portray the charismatic robot in ‘So Beautiful.’ The Heavy Metal movie will be a milestone in animation. and I’m proud to assist in its architectural structuralization.”

London also houses the production team for “Den,” “Soft Landing,” and part of “Grimaldi.” Among the “Den” crew, led by sequence director Jack Stokes—he too is an alumnus of Yellow Submarine—are some of the finest European animators working in the field today. Many are both Halas and Potterton grads. Animation miniatures expert Teru (Jimmy) Murakami was once the animation director for Frank Zappa and the head of a company that produced Puff, the Magic Dragon. He also directed the live-action feature film Battle Beyond the Stars. Elemental in his work is the elaborate combination of model work, rotoscoping, special effects, and air-brushing, all intended to make “Soft Landing” an opening sequence of visual wonderment. “If you could just get rid of the attitude that animation has to be cute,” reflects Murakami, “that would be great progress. I think a film like this could do that. It’s all a matter of getting the public to see animation as something other than cartoons. I’ve always tried to do animation that was more than that.”

In Malibu, “B-17” sequence director Barrie Nelson adjusts to the chore of animating the rousing horror treatment after building a career on the very opposite—whimsical, light shorts. Simultaneously, in Montreal, directors Julian Scuchopa and Paul Sabella cap off a career started at Potterton Productions by animating “Captain Sternn.”

And throughout the world, special-effects experts with hefty experience on such weighty effects masterpieces as Superman, Star Wars, and Star Trek toil away on Heavy Metal. Because of work on the film, even Disney has been affected. When word went out that ace cameraman Max Morgan modified his multiplane camera to do special shots in “Taarna,” the Disney Studios brought their original machine out of twenty-year-old mothballs.

With all of this, there are funny anecdotes that buoy up morale for such a massive and frantic community of animators. A Christmas card was circulated depicting Taarna lasciviously on Santa’s knee; graffiti in the men’s room in HM HQ read, “For a good time, call Taarna,” and listed the office phone number; the Ottawa studio doing “Harry Canyon” has an off-color guide to ethnic types of New York City in the future. But possibly the funniest was the “Bald Vagina” incident. After Gross and gang in London had a good look at the sex scene in “Den” where Kath makes the most of her nudity, they all noticed the reproduction of Corben’s bald vaginas on the storyboards. A memo went to producer Reitman asking about alternatives, or, “Do we go with the slit and damn the torpedoes?” The lines such a production inspires!

Finally, to pull the film together, Reitman concentrated on music as the work neared completion. First, the task of scoring the film went to maestro Elmer Bernstein. Master manager Irving Azoff pledged to spend any amount of money needed to assemble the best possible bands and songs for the two discs.

A world-renowned film composer, the 59-year-old Bernstein has won accolades and Oscars for his 130 film scores. The diversity is remarkable—True Grit, To Kill a Mockingbird, and National Lampoon’s Animal House are but a few. Azoff—a former midwestern college-concert promoter—now handles the heaviest of platinum-earning rockers, such as Steely Dan, the Eagles, and Stevie Nicks: auspicious credits but worlds apart in the music business. Yet, Reitman has delegated to these two the task of realizing the musical ambience of Heavy Metal. “It’s a matter of the degree by which you integrate different musical elements,” says Bernstein from his home-studio in Santa Barbara, California. “Obviously you pick music that stimulates a reaction. Since the animation medium is not lifelike, your music must really fit—it has to be something full, huge, adventurous.”

For Azoff, the assignment to gather various musical submissions to play for Reitman fell to Bob DeStocki, a burly ex-Ohioan and former Elektra-Asylum staffer. DeStocki must first interest world-class chart-topping bands, then convince them to send in original selections for consideration, and finally hustle them to finish acceptable demos for actual recording within the film’s deadlines. “Some of these guys have never done anything on deadline in their lives,” chuckles DeStocki, but it’s up to him to make them understand how unusual an opportunity this is—it’s the first time an animated film has tried for a totally original score. Of course, whom to ask troubled him because of his own initial unfamiliarity with the magazine. “It was soon clear that this movie is much more than one musical style.” Once DeStocki began looking, first in his own backyard and expanding outwards from there, he found bands agog with enthusiasm.

“When we got the script, it was like a dream come true,” says Blue Oyster Cult drummer Albert Bouchard. “And when I had read about the film just a few Heavy Metals before, I had hoped the music would be good. We always wanted to do a cinematic version of songs; we felt they demanded it. Now at least we get a chance to do something like that in reverse.” For the Cult, whose songs such as their hit “Don’t Fear the Reaper” have always had a macabre edge, doing the movie was more than a coincidence: it served to inspire the musical ideas for their upcoming album. “We didn’t really have any idea of what we were going to do and figured we’d wait till we got into the studio. Then, once we looked at the script, the music flowed, and we did five songs in a few days.”

For Black Sabbath lead singer Ronnie Dio, it was a similar opportunity to try something different. “We’ve always been interested in taking our audience beyond the realm of everyday life, so when we saw the script we said, ‘Perfect.’ Animation takes you out of the realm of the real, so we tried for some-thing that would take us out of the realm of what we ordinarily do.” The Cult and the Sabs treated their heavy-metal bombast to strong doses of electronics and extended instrumentals for the perfect effect.

But it was Devo’s Jerry Casale who summed up what the music in this film is all about. “Music in a soundtrack like this has to give an added dimension to it all. Since things are totally defined, the music should inspire the imagination.” Devo certainly tried for that, with two cuts that went beyond all expectations, “Be Cool” and “Working in Coal Mine” (the latter, says Gross, is the unofficial animator’s theme song). “So far other animated films have been limited to cartoonish images or the Bakshi style like in American Pop,” sums up Casale, explaining his own fascination with the HM idea. “An animated version of the magazine, which is so fantasy oriented, comes at an opportune time, especially in the wake of the sword-and-sorcery revival and the new Romantics things. There is a move toward re-evaluating our culture to make it seem more like a jungle, in order to make the familiar exciting again.”

Announcements

Newsletter

Browse by tag

Heavy Metal: The Making of the Movie (from August 1981)

Heavy Metal, the movie, had its premiere 40 years ago today—July 29, 1981—and opened nationwide a week later. To celebrate the anniversary we’ve got a treat for fans: The “Making of” article that ran in the August 1981 issue of Heavy Metal. This will bring back memories and will likely induce a strong urge to watch the film. Enjoy.

NOTE: Additional images have been added to this article

by Brad Balfour

Take 70 animators from 14 different countries, guys who have worked on everything from Sylvester the Cat to J.R.R. Tolkien’s hobbits. Put them in ten different studios stretching from the West Coast to London, with the nerve center in Montreal, somewhere in between. Give them characters and situations devised by writers who have previously written the highest-grossing Canadian film ever, and a director who has worked with such notables as Buster Keaton and Harold Pinter. Add to this already inspired mix astounding graphics and design sketches by some of the world’s hottest fantasy-art geniuses, artists loved and respected worldwide. Don’t forget a producer who at 27 started raking in bundles in Canada because he produced a young horror-filmmaker’s surprisingly good and profitable ideas, and later coproduced the 11th-highest-grossing film ever. Finally, base this on a magazine of illustrated science-fiction and fantasy stories, material of international renown, whose contents are reviewed in major French newspapers on a par with the way high art is covered, and whose illustrators include artists from Japan to the Netherlands. Take it all to Columbia Pictures, who distributed one of the finest science-fiction films in years, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, where the executives on the Burbank lot say, “This whole package is so fantastic, let’s make it our big film for the summer’s end.”

I’m talkin’ about Heavy Metal—the movie; talkin’ about Heavy Metal—the magazine.

And it was like something from a dream—the spirit of fate or the force of coincidence at work—that while publisher Len Mogel was in Paris negotiating rights with a small French publisher to produce a French version of National Lampoon, his wife, Ann, picked up a copy of their new magazine, Metal Hurlant. Both the Mogels were enthralled with its contents—illustrated science fiction and fantasy for adults laced with a strong dose of the absurd, drawn like fine art.

Mogel was determined to publish an English-language magazine presenting this new artistic concept, and he quickly won over his colleagues. Heavy Metal began publication in April 1977.

Mogel and crew found that after a mere five issues premiered, Heavy Metal quickly garnered over 100,000 readers. It was then that they knew they had something remarkable in hand. A year later—with the phenomenal success of Matty Simmons and Ivan Reitman’s National Lampoon’s Animal House as inspiration—the dream of a Heavy Metal movie took form.

The connection between comics and cinema is a natural one. Both deal in illusion, in actualized fantasy. Continuity of image and simple storytelling separate the successful story, told either in panel-art form or on celluloid, from the mediocre. The telling of a story through connected image and dialogue has been attempted since the first caveman painted sequential images on stone. Film is merely the execution of that idea in a modern way. As for the conjunction of comics and animation—well, what else could there be? Drawn images on a screen—drawn images on a page.

The Heavy Metal movie cried out to be animated. What else could capture the absurdist/dadaist/surrealistic urgings of the mag’s original art? Not live action, for then the extraordinary is rendered as the everyday. To keep the material in the realm of the imagined—in the region of mind that can plan out an entire world in sequential drawings—was the only appropriate choice.

Just imagine: a person draws, from nothing but disparate images in the head, a cohesive whole composed of hundreds of little scenes (the longest sequence in Heavy Metal consists of 330 scenes) made up of close to 130,000 individual drawings. Finally it’s the experience of an audience exchanging belief in the regular world of the photographic for the totally unreal world of the drawn, which then takes on a life of its own. And Heavy Metal, the movie, goes even beyond that.

It goes something like this, as one scriptwriter, Len Blum, puts it, “from one universe into another.” It opens with the “Soft Landing” sequence, based on art by Thomas Warkentin, from an idea of Alien scriptwriter Dan O’Bannon [originally published in the Sept. ’79 Heavy Metal]. After this 2001: A Space Odyssey–like prologue, it shifts rather handily into the quasi-mystical “Grimaldi” story—the key linking device be-tween sequences. From this intro we jump into “Den,” the adaptation of Richard Corben‘s brilliantly drawn quintessential hero fiction, which ran during HM‘s first year. It presented the greatest challenge to bring to the screen. Corben’s spectacular color values were carefully maintained in the backgrounds, with bizarre expanses glowing in rich, fluorescent hues. The tale of young Dan’s transformation into the hero Den, who’s caught in the power struggle between the sorcerer Ard and the queen-priestess, is told with two near-explicit sex scenes amidst lots of solid, hand-to-hand combat.

From these staggering visuals, the film carries us into the galactic court where Captain Sternn is on trial. From comic-artist great Berni Wrightson‘s original story [published in the June ’80 HM], Sternn is the ultimate parody of every space-opera villain-hero. Says artist Wrightson, “I’ve always had trouble writing something serious. So when Captain Sternn grew out of Star Wars—I was never an SF fan until I saw it—as a funny adventure, it degenerated into a broad farce. I was also inspired by Warner Bros. cartoons; hence I created his foil character, Hanover Fiste.” As the story leaves the conclusion of the trial, it moves into the “Neverwhere” world—master animator Cornelius Cole’s personal vision of the history of evil as a basic force in history. Cole’s visionary graphics (intricate ball-point renderings of lyric pastels) get most viewers to say, “Holy shit, this stuff is really coming to life!” Says Cole, “You reach a point in animation where you must have the opportunity not to cut corners.”

On to “B-17,” the first true horror story to be animated, with all the savagery that makes great shockers. Will Eisner–trained film artist Mike Ploog did most of the conceptualizations. His background as a former Marvel Comics “Conan” and “Frankenstein” artist lends greater power to this 1950s E.C. Comics–style terror tale. A favorite of producer Reitman’s since he was an E.C. collector as a kid, the story (based on an original idea of O’Bannon’s) was given a twist of authenticity. They visited an aviation museum, and one of the last few flyable B-17s was flown in order to record actual sound effects of the plane. Coincidentally, the HM animation team includes three WWII bomber crew-men, several licensed pilots, an ex-RAF inductee, and a director who collects aviation memorabilia.

With the following sequence, “So Beautiful and So Dangerous,” came the original artist, Angus McKie, who illustrated the serial in HM, which later became a book. He directly contributed 70 key background paintings of the most incredible animated sequences ever done. The contrast between McKie’s high-tech environments and the three space jockeys (well, two, and one robot) are inspired by Cheech and Chong. There are lots of outer-space drug references and some interstellar sex.

Gimenez’s “Harry Canyon” is an original depiction of a world half-familiar—New York City—in an unfamiliar time, 2031. The misadventures of a cynical cab driver caught in the middle of a battle for valuable stolen goods comes right out of a thirties detective story. “We sort of thought of it as an animated variation of Dashiell Hammett’s Maltese Falcon, starring Humphrey Bogart,” says the other scriptwriter, Dan Goldberg. This New York of the future is everything the current NYC is, only more: there’s Times Square with cheap, rip-off churches; a cop station that charges to aid the troubled; a Statue of Liberty no longer in the bay but surrounded by skyscrapers; and a Brooklyn Bridge graced with the sign “Use at your own risk.” Ironically, all of this was initially envisioned by the exceptional South American illustrator Juan Gimenez, who had never visited New York when he did the subtle drawings. He imagined a New York City unprejudiced by its reality—a reality that he discovered only weeks after his four-month drawing stint in Canada. When brought to New York to visit the HM office he saw the Pan Am building and exclaimed, “It really does exist as I saw it!”

Finally the clincher, the piece de resistance, the grand finale: the twenty-seven-minute-long “Taarna,” a sequence which boasts perhaps a dozen lines of dialogue. Without giving away too much, let’s say that “Taarna” evokes the sense of wonder that every animation fan, sword-and-sorcery fan, feminist-SF fan, female-anatomy fan, mythology fan, weird-landscape-and-wild-beastie fan, or special-effects fan ever desires. As the sequence director, John Bruno, put it, “It fits the perfect formula for animation; it’s something impossible to do in live action. It’s all illusion, really, like doing magic.”

Never before has such a diverse set of stories, themes, visual techniques, and drawing styles been sewn together in one integrated whole. Other films, such as the classic Fantasia, were anthologies, but the drawing style was generally one studio’s uniform product. Here the techniques of many of the world’s finest animators have been applied to this one film to make it a visual and emotional roller coaster, ranging from scenes of pure fantasy to shocking horror to light-hearted whimsy. And since the film’s full animation vision hopes to achieve a smooth and lifelike feeling, even the most fantastic depictions appear realistic. Because the film is so intimately linked with the magazine’s sensibilities, its artists played a substantial part in creating the striking cinematic visuals. Thus artist-superstar Richard Corben produced model sheets for the animated version of his hero Den, and famed comics artist (National Lampoon, “Son-o’-God,” Green Lantern) Neal Adams envisioned characters for “So Beautiful and So Dangerous.” Angus McKie, Mike Ploog (doing art not only on “B-17” but also on “Taarna”), and Juan Gimenez (who did more than just concept drawings; he also planned model sheets for both “Harry Canyon” and “B-17”) have lent their immense talents to the project. Even acclaimed illustrator Charles White III and Alex Tavolarous (designer for Francis Ford Coppola) fashioned art-deco-style cities for “Taarna.”

All this was done in order for the film to remain true to Heavy Metal, the mag. Through the magazine, adult subjects—particularly sexual ones—have been handled about as boldly as a comics-format magazine has ever handled them. And in the same adventurous spirit, the cinematic Heavy Metal also tackles realistic sex as it’s never been tackled before in an animated feature. To retain the realism of effect, the producers have stayed a mere hairbreadth away from an X rating. Nor has music been ignored: original pop music—written mostly for particular sequences—is set in an original score by Oscar-winning master composer Elmer Bernstein.

“For it to really capture the spirit of the magazine, it had to be an anthology,” says Mogel from behind his classically huge publisher’s desk. “What individual story could we have picked that represented the varied dynamics of the magazine and made one long, interesting story?”

It took Mogel from the summer of ’78 until the close of ’79 to develop the movie package. During that frenzied period, he had seen his project accepted, then rejected, by two major studios; he lost the story rights for three major illustrated works, had his animation budget doubled, and, during the whole process, earned his Ph.D. in determination.

In December ’79, Mogel decided to pursue the film’s financing in Canada. He called associate Simmons in Los Angeles and asked if he would consult his Animal House coproducer, Reitman, on the legal and governmental aspects of Canadian filmmaking. Reitman, a Canadian, got on the phone with Mogel and discussed the project as a whole.

One hour later, fascinated by the film’s possibilities, he told Mogel, “I can get the money and would like to produce it—let’s go.” Later, as he reflected on that decision, “it seemed like a great idea. I’d never seen an animated film since early childhood that excited me, so I thought it would be a challenge to make one.” The Toronto-born filmmaker adds, “Anyhow, I’ve seen most of the science-fiction and fantasy films ever made. I’m a big buff, so I really wanted to do an adult fantasy.”

Evidently, Columbia Pictures execs agreed with the wisdom of Reitman’s decision. Encouraged by his work for them on Stripes, they decided in late 1980 to distribute Heavy Metal, the movie.

But making the picture sounded simpler than reality has proven it to be, for even with its by-then tripled budget, no one fully comprehended what a massive undertaking was about to get underway. Nobody really could have, for they were attempting to do something not done before, bringing together all these diverse talents under one banner.

But Reitman hasn’t blanched at challenges. When he finished college in Toronto, Reitman formed a college-film distributing company, which gave him his first taste of film business. Then, at 25, he jumped into directing his first feature, a tongue-in-cheek horror number, Cannibal Girls—no great shakes as art but a drive-in money-maker. Finding out that his forte was making films, Reitman shifted to producing and hit big from the start, producing nouveau-horror-great director David Cronenberg’s first feature, They Came from Within—a controversial money-maker, and then Rabid. Shortly afterwards came National Lampoon’s Animal House. His fortunes further increased when he produced Meatballs, with Bill Murray, who now stars in Reitman’s comedy Stripes.

“I knew I had to tell a good story; that’s a basic of good moviemaking,” Reitman says assuredly. And with his own longtime love of comic books and the original Mad comic, he’s well suited to producing HM. “I knew it wouldn’t work as a regular movie,” the 35-year-old Canadian says. But he also knew it wasn’t that simple. “Though the artwork makes the magazine, you get bored with animation, the wonder of the designs, after ten minutes. So I figured, if we put together segments of shifting designs and story approaches, yet make them somehow connected, we could have the best of all worlds.”

So, when Reitman and fellow-Canadian scriptwriters Dan Goldberg and Len Blum jumped into mega-hour writing sessions late in February 1980, they pounced on making the film as broad as possible. To do so, this trio employed the same extrapolative techniques that make great science fiction work. “At each stage of the script,” explains Blum, “we had detailed understandings about each character and situation, which were not fleshed out in the script.” They remained true to the magazine’s values and even used a bit of method-acting thinking. There is an exercise which requires knowing a character’s whole life in order to play an hour of it; their knowledge of each character had to be more than what ends up on the screen.

“For example, although you never know it on the screen,” explains Blum, “we knew that Zeke and Edsel, the space jockeys from ‘So Beautiful…,’ rocket around the galaxy collecting defective robots from various solar systems; they’re like outer-space Xerox repairmen.” These two writers also intended “Grimaldi” to have a strong mystical dose; made sure “Den” was a resolution of the teenage sexual fantasy; and made “B-17” as timeless a tale as possible.

To further insure Heavy Metal‘s visual success, former National Lampoon art director Michael Gross came to the project early on to maintain visual integrity. He became an associate producer, aiming to maintain quality all the way down the line. Gross, as an award-winning art director, conceived and edited the Lampoon‘s innovative comics pages and designed The Book of Alien.

Since the film was being financed in Canada—watchdogged by associate producer/financial manager Peter Lebensold—the HM animation headquarters was in Montreal, Canada, as well. Fortunately, this city is home to the acclaimed animation director Gerry Potterton. Executive producer Mogel had known of Potterton long before the Canadian financing, but once it became apparent that Canada was the place, Potterton fit right in like a puzzle piece.

Perfect, too, to have ex-Britisher Potterton at the helm, for this easygoing fifty-year-old director has done not only classic animation, like the “Raggedy Ann and Andy” feature, but live action as well. Potterton’s professional associations spanned the globe, so he was able to assemble what became the largest single animation operation in the Western world (400-plus personnel). And each of the many people involved has worked on at least one major animated project completed in the last 20 years.

Here in the Montreal nerve center on the third floor of the former Concordia University (incidentally, an art college) classrooms, Potterton does what no live-action director and few animation directors have ever done—that is, directs eight sequence directors, directing their individual segments. And he handles nearly sixty-five animators, each of whom is an artist who becomes an actor as he illustrates each character he’s supposed to portray. When a live-action director asks an actress to cross a set, she automatically sets body to motion; but an animator must consider not only the fact of that action but also its consequences: if the character is naked, then breasts bob; if clothed, fabric wrinkles. It’s a task of great detail and individual interpretation. The animation director is aware, too, of all that the animator can bring to or alter in a scene. All this Potterton must manage, as well as oversee the physical production of every stage from storyboard to final animation.

“My nature is to jump around, so it lends itself to making this film,” Potterton admits inside his office, jam-packed with Ploog sketches, where a production assistant is busily at work. He first got into animation at the Halas and Batchelor Studios, where 1954’s great breakthrough Animal Farm feature was made. “Unlike in live action, one thing’s for sure: you have to have a basic talent—drawing—to get into animation.” From there Potterton emigrated to Canada, eventually forming his own production company, which went on to do numerous TV specials, animated features, and live-action films, until its recent dissolution. While in a hiatus, he was offered the challenge of Heavy Metal. “You meet live-action people who say, ‘I wish I could do animation.’ It seems to me a hell of a lot easier to make the transition from animation to live action because you’re trained from the start to visualize in terms of already edited scenes. In animation, you can’t afford to shoot a scene several different ways; you must know what you want and do it right the first time!”

And here in Montreal they have guys giving him what he wants, guys like Portuguese-born Parisian Jose Abel, the animator of the young boy’s death scene in “Taarna.” When the kid goes to warn the council of a barbarian attack, he’s shot down, and Abel visualizes his body falling, the arrows piercing his throat, his eyes rolling back in his head, his tongue lolling out, and finally, the hands falling away in death. All in a few seconds. Some of the cel-colorists (ink-and-paint people) refused to work on the scene because it was so realistic. “You have to believe in what you are doing. You must somehow make it exist. You must forget it’s a drawing.”

They’ve done the job for Potterton in other places as well. Howard Chaykin holed up in LA’s Universal Sheraton for ten days drawing umpteen pictures a day. This illustrates perfectly the fanaticism surrounding the production. “I played the Philip Marlowe of animation! Since I was asked to create eclectic drawing for the ‘Taarna’ sequence, I had to avoid making them Conan clones or making Taarna another Barbarella. So I hid away and concentrated on Japanese design, which has that SF sort of stylization anyhow.”

In London, the grandiose sign announcing Halas and Batchelor greets the visitor to Europe’s premier animation studio and theater for work on “So Beautiful.” Inside, major domo John Halas speaks of life with the late great SF film director George Pal in their native Budapest. The 69-year-old Halas now dominates world animation unlike anyone else this side of departed demigod Walt Disney. “In various spheres of art come those who define it; I am one in animation.” Possessing a track record that includes the brilliant, subtly political Animal Farm (Britain’s first full-length animated film); the Oscar-nominated Automania 2000 and Dream Doll; and the electronic-music-inspired “Autobahn” short, Halas can speak with authority: “Only animation can provide the humor and personality needed to portray the charismatic robot in ‘So Beautiful.’ The Heavy Metal movie will be a milestone in animation. and I’m proud to assist in its architectural structuralization.”